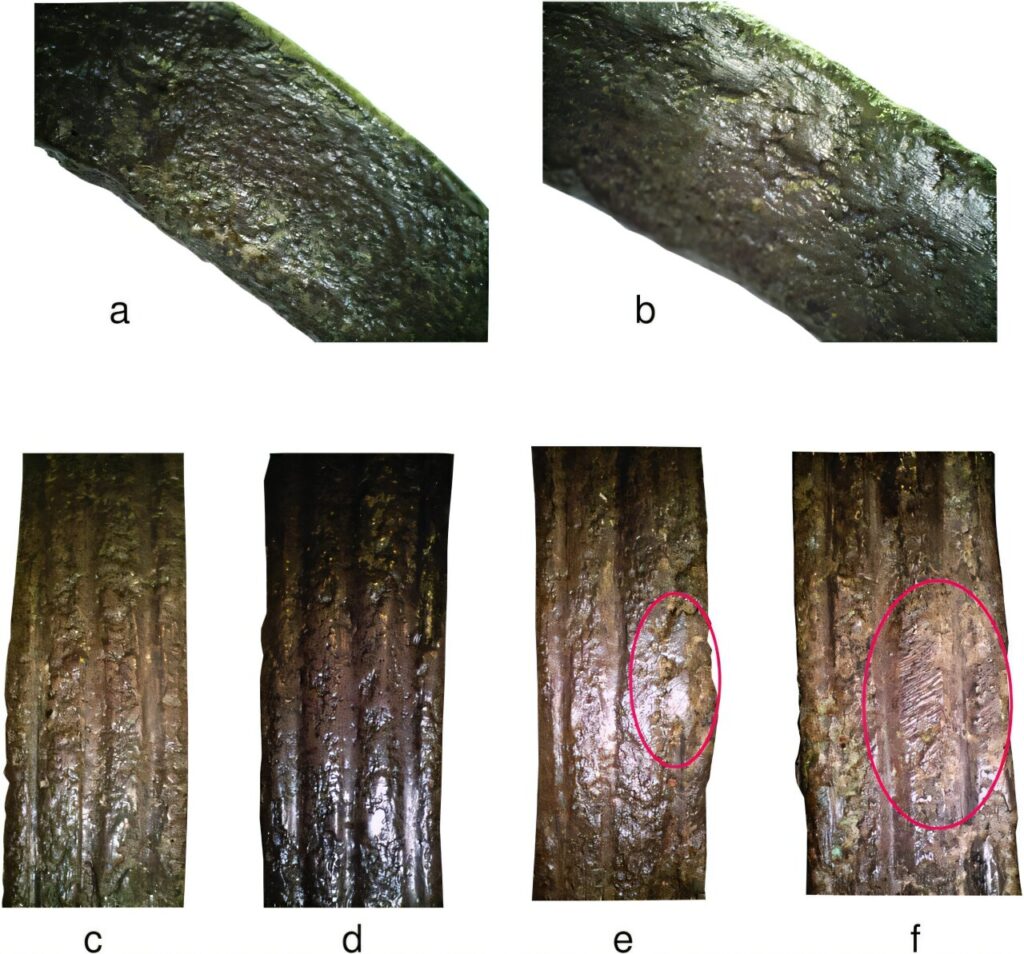

When a single silver bangle was lifted from the earth in 1884, no one could have guessed it would one day rewrite a chapter of ancient European technology. It came from Grave 292 of the El Argar culture in southeastern Spain, a Bronze Age society that flourished between 2200 and 1550 BC. The brothers Henri and Louis Siret, assisted by Pedro Flores, excavated it on a warm spring day, carefully noting its strange appearance. Their own words from 1890 captured its peculiarity. They described it as “one of a different and unique shape, on the other hand, found in grave number 292. It is a continuous silver strip, on whose outer contour parallel longitudinal grooves have been made as if they had wanted to represent separate spirals.”

More than a century later, that brief note would become the doorway to a surprising discovery. Modern analysis has now revealed that this bangle is the first known example of lost-wax casting of silver objects in Bronze Age Iberia—and so far, in all of Western Europe.

The finding comes from a study published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology by Dr. Linda Boutoille. It is not simply a technical revelation. It is a window into a vanished world where craftsmanship, power, and secrecy may have intertwined in ways we are only beginning to understand.

A Culture That Loved Silver

The El Argar culture has long stood out for its unusual relationship with silver. Unlike most Bronze Age societies in Europe, its people used silver abundantly, particularly in their funerary traditions. Burial sites are filled with ornaments that signaled status and identity. Many of these objects were uncovered by the Siret brothers during their remarkable years of excavation between 1884 and 1889. Later, the objects were acquired by L. Cavens and donated to the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels in 1899, where the great Siret Collection still resides.

Inside this vast archive of Bronze Age craftsmanship, one bangle stood alone. It was unlike any other object from the El Argar name-site, unique not only in appearance but, as it turned out, in the way it was made.

Wax, Fire, and Metal

Lost-wax casting is a technique that feels almost magical in its simplicity and precision. First, an artisan sculpts the desired object in wax. That wax model is then coated in layers of clay. When the clay shell hardens and is heated, the wax melts away, leaving behind a hollow space exactly matching the original shape. Into this negative mold, molten metal is poured. When the metal cools, the clay mold is broken to reveal a solid metal object that preserves every detail of the wax model.

It is a method that requires not only skill but planning, patience, and confidence in the invisible process taking place inside the clay.

According to Dr. Boutoille’s analysis, the Grave 292 bangle was made this way. The fine grooves described by the Siret brothers were not hammered or cut—they were born from wax.

Other El Argar artifacts might also have been created using lost-wax casting, but their surfaces are too corroded to be sure, and some objects have been lost over time. For now, the Grave 292 bracelet is the clearest evidence we have, a single shining clue.

Dr. Boutoille emphasizes its singularity. “The bracelet under study is unique within the El Argar assemblage—and indeed within Europe. No direct parallels have been identified elsewhere, although later examples from Cabezo Redondo near Alicante show some resemblance.”

Uniqueness, in this case, complicates the story. Without parallels, there is no easy way to link this technique to broader European or Mediterranean traditions. As Dr. Boutoille explains, “All known lost-wax cast artifacts from the El Argar Culture appear to be unique pieces, making it challenging to relate them to broader European or Mediterranean productions. At the current stage of research, if we exclude the possibility of knowledge transfer from Central, Eastern European, or Mediterranean sources, no clear evidence supports such a transmission.”

Here is where archaeology becomes detective work. The artifact gives clues, but it also raises questions that resist easy answers.

Secrets of the Elite or Experiments in Silver

One of the most intriguing aspects of the discovery is what it suggests about social and technological boundaries in El Argar society.

Dr. Boutoille notes that “evidence for beeswax processing and lost-wax cast objects is confined to specific areas of sites containing the richest, elite burials. This pattern suggests that such techniques were probably restricted to the upper echelons of society, rather than relating to the quality of workmanship per se …”

In other words, the craft may have been a privilege.

Yet the bracelet itself is imperfect. Its design is unusual, its execution perhaps uneven. Could it have been a novice’s attempt, a learning piece made by someone experimenting with the technique? Dr. Boutoille sees this as a possibility. “The imperfect bracelet could represent a learning or experimental piece, but with only a single example to hand, it remains impossible to draw firm conclusions.”

She also considers other explanations. “Another possibility is that such production may have occurred within elite households, contrasting with the output of specialist craftsmen … Lastly, it may be the process itself, rather than the finished quality, that was especially prized; the adoption of lost-wax casting could have imparted an aura of fashion or status.”

Here the narrative opens into a human moment. Imagine a craftsperson in a wealthy household, shaping a spiral bangle in wax, uncertain whether the molten silver will flow correctly into the mold. Or imagine an elite family valuing the object not for its perfection but for the knowledge that it came from a rare, almost mystical technique. As Dr. Boutoille adds, “It is conceivable that only a select group of metalworkers had access to or expertise in this process, with some achieving a high standard of artistry, and others either less skilled or still in training.”

Whatever the case, the bracelet speaks to a society where technology was not just a tool but a marker of identity and power.

The First Step in a Long Investigation

Dr. Boutoille makes clear that this discovery is just the start. “This paper represents the inaugural publication of a project … and will be succeeded by a series of further articles, alongside a comprehensive catalog documenting all the metal artifacts from the Siret collection housed at the Royal Museums of Art and History (MRAH).”

Her upcoming work will examine artifacts not only from El Argar itself but also from sites such as Fuente Álamo, Gatas, El Ofício, and La Bastida. She aims to understand where lost-wax casting fits into the wider technological traditions of Bronze Age Iberia and Western Europe.

“I aim to explore the significance and influence of lost wax casting within the El Argar culture and its broader metallurgical practices. I intend to extend my research on lost wax casting across Iberia and Western Europe, in order to deepen our understanding of its origins, evolution, and role within the metallurgical traditions of the Bronze Age.”

It is an ambitious path, but the bracelet has opened the door.

Why This Discovery Matters

The Grave 292 bangle is more than an artifact. It is a challenge to long-held assumptions about the spread of technology in ancient Europe. Before this study, lost-wax casting of silver was not known in Western Europe during the Bronze Age. Now, one object pushes that boundary back in time, hinting at innovation, specialization, and perhaps social exclusivity within a culture already remarkable for its use of silver.

It reminds us that the past is rarely simple. A single bracelet can shift the entire narrative of technological development. It can reveal hidden skills, forgotten traditions, or connections that leave no other trace.

Most importantly, discoveries like this show that ancient societies were inventive in ways we are still discovering. The people of El Argar were not merely using metal. They were experimenting, refining, and perhaps even competing in the art of making it.

In the gleam of one imperfect bracelet, we see the spark of human creativity that transcends time.

More information: Linda Boutoille, First evidence of lost‐wax casting in the earlier Bronze Age of south‐eastern Spain: The silver bangle from El Argar, Grave 292, Oxford Journal of Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1111/ojoa.70005