About 9,500 years ago, at the base of Mount Hora in what is now northern Malawi, a fire burned unlike any other. It was not a cooking fire or a campfire meant to hold back the night. It was deliberate, sustained, and deeply intentional. Around it gathered a community of hunter-gatherers who carried out an act that, until now, had never been documented in Africa’s ancient foraging past.

They cremated a small woman on an open pyre beneath a granite overhang, using fire not only as a tool, but as a ritual language. Her body was transformed into ash and fragmented bone in a spectacle that demanded time, labor, fuel, and collective purpose. Nearly ten millennia later, traces of that fire have spoken again.

A new study published in Science Advances reveals that this was the earliest known intentional cremation in Africa and the oldest in situ cremation pyre ever discovered containing the remains of an adult. It is a finding that reaches across deep time and quietly asks us to rethink what we believe about the emotional and social lives of ancient African hunter-gatherers.

The Place That Remembered

Mount Hora rises suddenly from the surrounding plain, a granite inselberg standing several hundred feet tall and visible from afar. At its base lies a sheltered spot known as Hora 1, tucked beneath a rock overhang. Archaeologists first explored this location in the 1950s and recognized it as a burial ground used by hunter-gatherers, though its age remained uncertain.

Decades later, renewed research led by Jessica Thompson of Yale University revealed a far deeper story. Beginning in 2016, her team showed that people had inhabited this site as early as 21,000 years ago. Between about 16,000 and 8,000 years ago, the overhang became a place of burial. The dead were interred whole, laid to rest intact beneath the stone shelter.

Then, around 9,500 years ago, something changed.

Within the same sacred space, an ash-filled feature appeared, roughly the size of a queen bed. Unlike the other burials, this one contained no intact body. Instead, it held the remains of a single individual reduced by fire. No similar cremations came before it at Hora 1. None followed.

Reconstructing an Ancient Moment

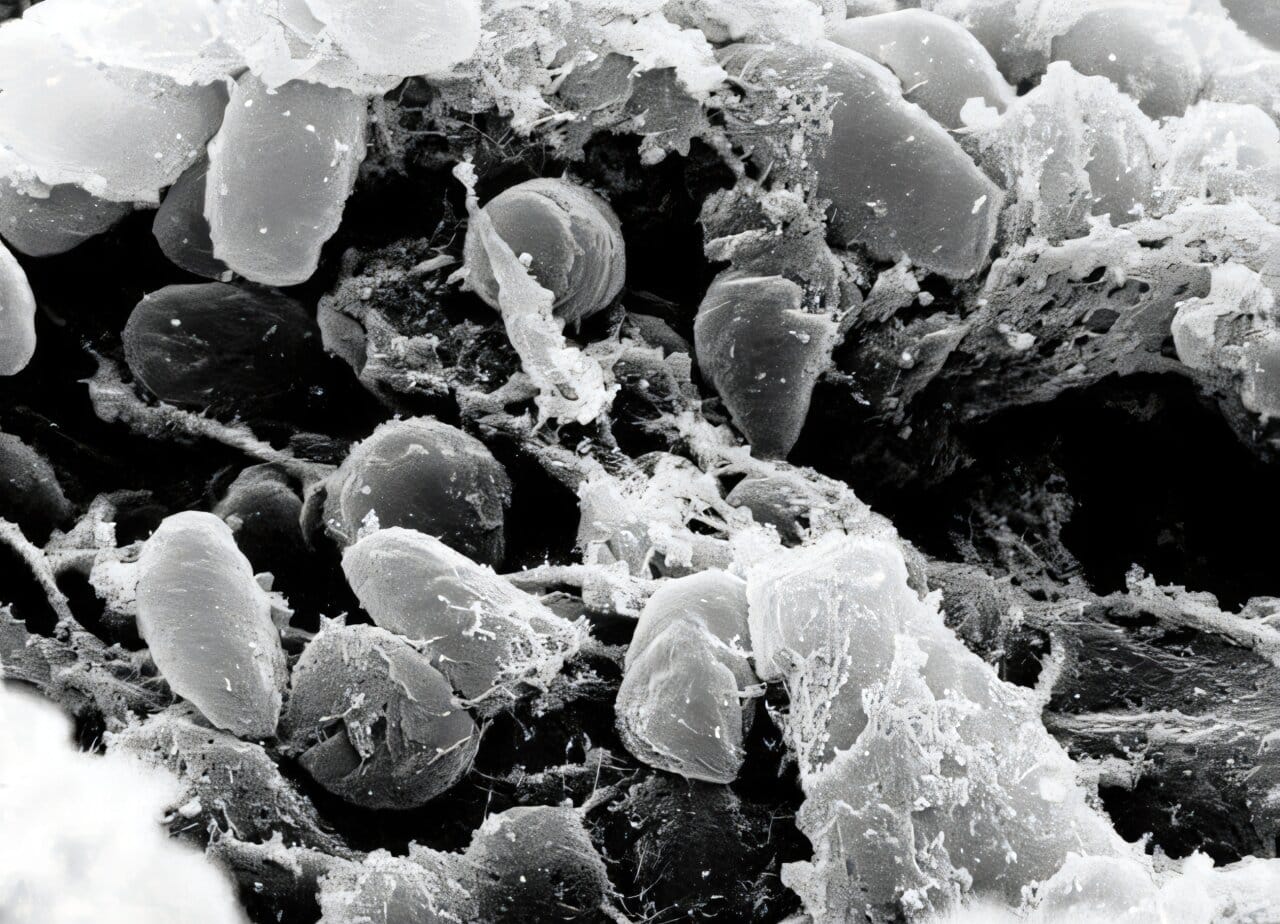

To understand what happened at Mount Hora, researchers drew on a wide range of methods, weaving together archaeology, geospatial analysis, forensics, and bioarchaeology. Under microscopes, they examined the sediments of the ash layer. They analyzed each fragment of burned bone, searching for clues hidden in patterns of heat and breakage.

From this painstaking work emerged a remarkably detailed reconstruction of events.

At least 170 fragments of human bone were recovered, most belonging to the arms and legs. The bones told the story of an adult woman, between 18 and 60 years old, just under five feet tall. The patterns of thermal alteration showed that her body was burned before decomposition began, likely within days of her death.

Cutmarks on several limb bones revealed that parts of her body had been defleshed or removed before the fire was lit.

“Surprisingly, there were no fragments of teeth or skull bones in the pyre,” said Elizabeth Sawchuk, Curator of Human Evolution at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and a bioarchaeologist involved in the study. “Because those parts are usually preserved in cremations, we believe the head may have been removed prior to burning.”

The absence of the skull was not an accident of preservation. It was a decision.

The Labor of Fire

Cremation is not a simple act, especially for hunter-gatherers. To burn a body down to calcined bone and ash requires sustained high temperatures and constant attention. At Mount Hora, the evidence shows that the fire was actively managed.

Researchers estimate that at least 30 kilograms of deadwood and grass were gathered to build the pyre. Fuel was added repeatedly, and the fire was disturbed and manipulated as it burned. The ash and bone fragments indicate temperatures exceeding 500 degrees Celsius.

Stone tools were found within the pyre itself, suggesting they were placed into the fire intentionally or became embedded during the burning. They may have served as funerary objects, offerings carried into the flames alongside the body.

“Cremation is very rare among ancient and modern hunter-gatherers, at least partially because pyres require a huge amount of labor, time, and fuel to transform a body into fragmented and calcined bone and ash,” said lead author Jessica Cerezo-Román, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Oklahoma.

This was not an act of convenience. It was a communal undertaking, one that would have required planning, coordination, and shared meaning.

A Ritual That Stands Alone

What makes the Mount Hora cremation even more striking is how singular it is. Before and after this event, the site continued to be used for burials, all of them involving complete bodies placed intact beneath the overhang. No other individual at Hora 1 received the same treatment.

Elsewhere in the world, burned human remains appear much earlier, such as at Lake Mungo in Australia around 40,000 years ago. But intentionally constructed pyres do not enter the archaeological record until nearly 30,000 years later. Before Mount Hora, the oldest known in situ cremation pyre was dated to about 11,500 years ago at the Xaasaa Na’ site in Alaska and contained the remains of a young child.

In Africa, definitive evidence for cremation was previously limited to around 3,500 years ago, associated with Pastoral Neolithic herders rather than hunter-gatherers. Cremation has generally been more common among food-producing societies with more complex technologies and elaborate mortuary traditions.

The Mount Hora pyre defies those expectations.

“Not only is this the earliest cremation in Africa, it was such a spectacle that we have to re-think how we view group labor and ritual in these ancient hunter-gatherer communities,” said Thompson.

Memory Written in Ash

The story of the pyre did not end when the flames died down.

Evidence shows that about 700 years before the cremation, the same location had already been used for large fires. Then, within 500 years after the cremation, people returned to light multiple additional large fires directly atop the pyre itself. These later blazes did not involve burning human bodies, yet they were deliberately placed at the same spot.

This pattern suggests memory. It suggests that generations remembered where the cremation had taken place and recognized its importance. The repeated use of fire transformed the location into something more than a burial ground. It became a landmark of ritual significance, tied to social memory and identity.

“These hands-on manipulations, cutting flesh from the bones and removing the skull, sound very gruesome, but there are many reasons people may have done this associated with remembrance, social memory, and ancestral veneration,” said Cerezo-Román. “There is growing evidence among ancient hunter-gatherers in Malawi for mortuary rituals that include posthumous removal, curation, and secondary reburial of body parts, perhaps as tokens.”

Within this framework, the cremation was not an isolated act of violence or disposal. It was a carefully structured ritual embedded in a long-standing tradition of place-based meaning.

The Question That Remains

Despite the clarity surrounding how the cremation occurred, one question resists every analytical tool the researchers applied.

Why her?

Why was this one woman cremated when all others at the site were buried intact? Why was her skull removed? Why was so much effort invested in a ritual that stands alone in the site’s long history?

“Why was this one woman cremated when the other burials at the site were not treated that way?” Thompson said. “There must have been something specific about her that warranted special treatment.”

The archaeological record offers no name, no story, no direct answer. What it preserves instead is evidence of intention, care, and remembrance. Whatever made this woman different was deeply understood by the people who gathered at Mount Hora that day.

Why This Discovery Matters

The Mount Hora cremation matters because it challenges long-held assumptions about ancient African hunter-gatherers. It shows that their social and ritual lives were not simple or uniform. They were capable of complex mortuary practices that required coordination, symbolism, and emotional investment.

This discovery expands the known timeline of cremation in Africa by thousands of years and places sophisticated ritual behavior firmly within foraging societies. It reveals that fire was not only a practical tool, but a medium through which memory, identity, and meaning were expressed.

Most of all, it reminds us that deep in the past, people grappled with death in ways that were thoughtful, deliberate, and profoundly human. At the foot of Mount Hora, fire became a language of remembrance, and through the quiet persistence of ash and bone, that language has finally been heard again.

More information: Jessica Cerezo-Román et al, Earliest Evidence for Intentional Cremation of Human Remains in Africa, Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adz9554. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adz9554