In the quiet ruins of Chaco Canyon, where sandstone walls still hold the memory of voices long gone, a different kind of presence once filled the rooms. It was not human, yet deeply woven into human life. Brilliant feathers, sharp calls, and watchful eyes belonged to macaws and parrots that lived, died, and were carefully placed within the great houses of an ancient world.

A recent study by Dr. Katelyn Bishop returns to these birds, not as symbols pulled from distant stories, but as physical beings whose bones still rest in the canyon. By reexamining zooarchaeological remains and archival records, the study seeks to understand how these birds were kept, where they were placed, and what their presence reveals about the relationship between people and animals in ancient Puebloan society.

Published in the journal KIVA, the research does not chase mystery for its own sake. Instead, it listens closely to context. Where were the birds found. What surrounded them. How were they treated. Through these details, a quieter but richer story begins to emerge.

A Canyon Full of Sites and Silences

Chaco Canyon was inhabited from the mid-800s to around the mid-1100s, a span of centuries that saw the construction of thousands of archaeological sites. Some were large, multi-storied pueblos built of masonry, known as great houses. Others were smaller pithouses and pueblos scattered across the canyon and its surrounding mesa tops.

Despite this abundance, much of Chaco Canyon remains unexcavated. As Dr. Bishop explains, “…there are many sites in Chaco Canyon, the vast majority of which have not been excavated. Out of a dozen ‘great houses’ (large, multi-storied pueblos of masonry construction), only two have been completely or nearly completely excavated, to say nothing of the more than 1,000 smaller pueblos and pithouse sites throughout the canyon and its surrounding mesa tops.”

Within the limited areas that have been excavated, the remains of macaws and parrots have long drawn attention. Scholars have debated how these birds arrived in Chaco Canyon and why they were valued so highly. Yet for all the discussion, few studies have closely examined the bird remains themselves. The last complete analysis was published more than 50 years ago and contained inaccuracies and limited contextual detail.

Dr. Bishop’s work steps into that gap, not by speculating, but by carefully reassembling what the evidence itself can say.

The Meanings Carried on Red and Blue Wings

Macaws are not ordinary birds in Pueblo traditions. Their colors, movements, and voices have long carried layers of meaning. Drawing from ethnographic and ethnohistoric accounts, Dr. Bishop explains that “…based on ethnographic and ethnohistoric accounts, scarlet macaws have associations with the sun, the sky, rain, rainbows, salt, and the south. They factor into directional symbolism, where they represent or stand in for the southern direction. Their red color associates them with the sun, and their multiple other colors (primarily blue and yellow) to the rainbow, and consequently to the rain. Their feathers have been used for centuries; they feature in many Pueblo stories, and multiple pueblos have or have had a macaw or parrot clan.”

These accounts offer important insight, but Dr. Bishop is careful to emphasize their limits. “While 19th and 20th-century ethnographic accounts give insight into their symbolic associations, contemporary Pueblo communities remain the experts on the current and past importance of scarlet macaws.”

The new study does not attempt to redefine those meanings. Instead, it focuses on how the birds were physically treated within Chaco Canyon, grounding interpretation in archaeological context rather than assumption.

Counting the Birds, One by One

Through a comprehensive reanalysis, Dr. Bishop identified a total of 45 birds recovered from Chaco Canyon. Of these, 42 were macaws and three were thick-billed parrots. None of these birds were historically native to the region. Physical zooarchaeological analysis could be conducted on 38 individuals, as four macaws and all three thick-billed parrots could not be located.

These birds came from five sites across the canyon. The great houses Pueblo Bonito, Pueblo del Arroyo, Kin Kletso, and Una Vida each yielded remains, along with a site known as 29SJ 1360. The distribution was not even. The overwhelming majority were recovered from Pueblo Bonito, the most famous and extensively studied great house in Chaco Canyon.

Within Pueblo Bonito alone, 35 macaws and two thick-billed parrots were found. Their locations within the structure would prove crucial to understanding how these birds lived and how they were treated after death.

Room 38 and the Evidence of Daily Life

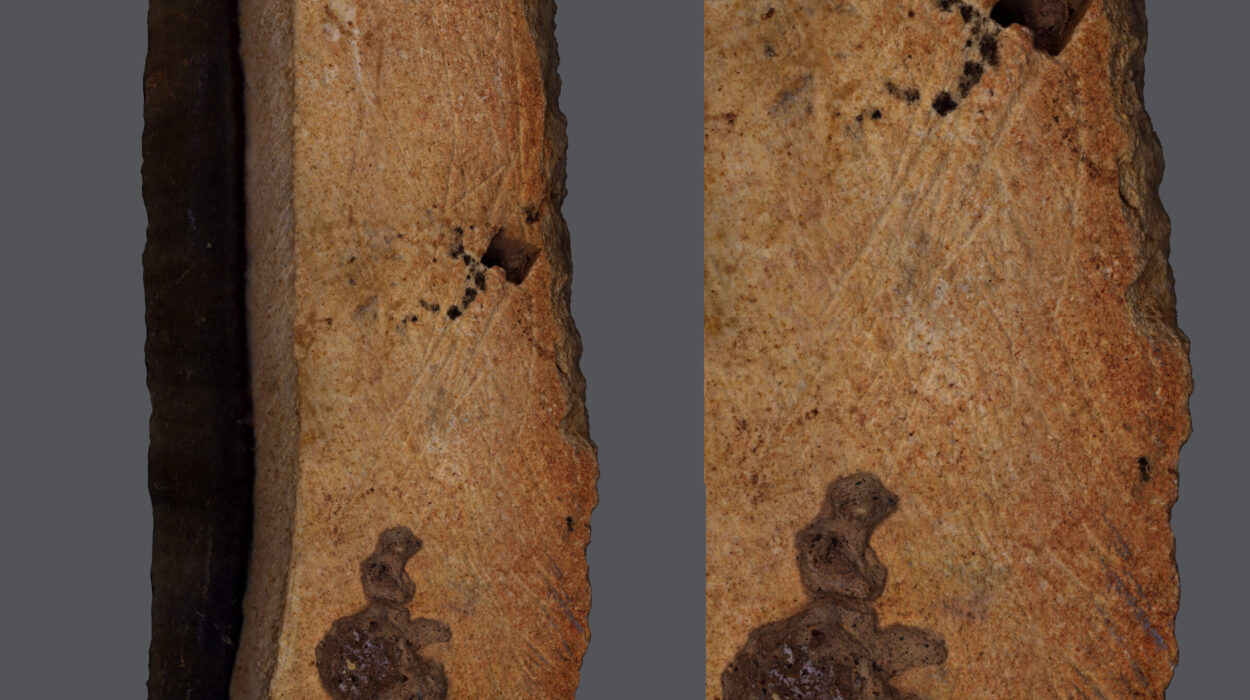

Most of the birds at Pueblo Bonito were recovered from the earlier northern arc of the building, particularly from a space known as Room 38. This single room contained the remains of 14 scarlet macaws. Two of these had been intentionally buried in a subfloor pit, suggesting deliberate placement rather than casual disposal.

The remaining twelve told a different story. They were found in a layer of droppings nearly ten inches thick against the east wall. This accumulation suggests that the birds spent extended periods in the room, likely perched along that wall. The presence of droppings points to living animals, not simply ceremonial deposits. The birds appear to have been housed there over time.

The ages of the macaws strengthen this picture. They ranged from as young as 11 to 12 months to individuals more than 25 years old. These birds were not acquired all at once. They arrived over a span of roughly 250 years, indicating long-term commitment rather than a single event.

Room 38 does not read as a place of neglect or indifference. Instead, it feels inhabited by living creatures whose needs were recognized and accommodated.

A Shelved Room Reached from the Sky

Another space in Pueblo Bonito, known as Room 249A, offers further insight. This room featured an adobe-plastered shelf covered in bird droppings and food remains. The evidence suggests birds were kept perched there. The room itself was accessed through a roof hatch, adding another layer to its story.

This was not a casual arrangement. The plastered surfaces, the controlled access, and the clear signs of feeding all point to intentional care. These birds were not wandering freely through the pueblo. They were housed in specific rooms designed to support their presence.

Across the other sites in Chaco Canyon, birds were found only in small numbers or in isolation. The pattern is clear. Macaws and parrots were overwhelmingly associated with great houses, and especially with Pueblo Bonito.

Deposited Whole, Kept Warm

Perhaps one of the most striking findings of the study comes from what was not found. Among the 2,481 bones examined, none showed evidence of butchering. The birds were not cut apart or processed for meat. Instead, they appear to have been deposited whole.

This suggests that when these birds died, their bodies were treated with care. They were placed intentionally, not discarded as refuse. Their final resting places were often large rooms with plastered walls and thermal features. These rooms would have retained heat, indicating that keeping the birds warm was a priority while they were alive.

An additional pattern emerged alongside the macaws. Magpie remains were sometimes deposited with them. Dr. Bishop notes this may reflect color symbolism or a shared ability to mimic human speech. While the meaning remains open to interpretation, the association itself appears deliberate.

Together, these details point toward a relationship defined by attention and intention.

Rethinking Care, Rethinking Assumptions

Dr. Bishop’s study of macaws is part of a larger examination of all avian remains from Chaco Canyon. Birds of many kinds appear throughout the archaeological record. As she notes, “Many other types of birds were important to Chaco’s inhabitants, including turkeys, eagles, hawks, cranes, doves, pigeons, woodpeckers, quail, and songbirds of many different kinds. Birds, as a class of animal, seem to have been extremely significant. I’m looking forward to focusing on those relationships between people and types of birds other than macaws.”

When it comes specifically to macaws, Dr. Bishop urges caution against long-held assumptions. Some skeletal remains show signs of pathology, but the causes are not well understood. “With regard to the macaws specifically, I think a better understanding of skeletal pathology is needed. There are a number of pathological markers on macaw remains, but our understanding of the cause of some of these pathologies is lacking.”

She challenges a common narrative directly. “There has been a tendency in prior discussions of the Chaco macaws to assume that these birds were mistreated, and I don’t think that that’s necessarily or inherently true.”

Instead, the evidence points in another direction. “I think there is a great deal of evidence for the many ways that these birds were cared for, provided for, and valued.”

Why These Birds Still Matter

This research matters because it reshapes how we see relationships in the past. The macaws of Chaco Canyon were not distant symbols or exotic curiosities alone. They were living beings integrated into daily and ceremonial life, housed with care, kept warm, and deposited with intention when they died.

By focusing on where the birds were found and how they were treated, the study grounds cultural interpretation in physical evidence. It shows that meaning is not only carried in stories and symbols, but also built into walls, shelves, and layers of droppings that mark the passage of time.

More broadly, the study reminds us that archaeology is not just about objects. It is about relationships. Between people and animals. Between belief and practice. Between care and memory.

In the stone rooms of Chaco Canyon, the echoes of wings still linger. Through careful reanalysis, those echoes are beginning to speak again, telling a story not of mystery alone, but of connection, responsibility, and respect that crossed species boundaries centuries ago.

More information: Katelyn J. Bishop, Reconstructing Context for the Macaws and Parrots of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, KIVA (2025). DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2025.2505360