For generations, a familiar story has drifted through textbooks and popular imagination: that before the British arrived in 1819, Singapore was little more than a quiet fishing village. It is a simple story. A peaceful shoreline. A handful of boats. A sleepy past.

But deep beneath the waters off Singapore’s coast, another story was waiting.

Sometime in the middle of the 14th century, a merchant ship sank near the island once known as Temasek. The sea swallowed it whole. The wood decayed. The structure disappeared. For centuries, it lay hidden, undisturbed in the dark.

Then, between 2016 and 2019, archaeologists carefully excavated what remained. Not the hull. Not the masts. But something just as revealing: a 3.5-tonne cargo haul of Chinese ceramics resting silently on the seabed.

This shipwreck, now known as the Temasek Wreck, is the earliest known shipwreck in Singapore waters. And its cargo has begun to rewrite the story of Singapore’s past.

Shards That Spoke of Distant Kilns

When the ceramics were lifted from the sea, most were broken. Shards of bowls. Fragments of plates. Pieces of jars. Yet even in fragments, they spoke.

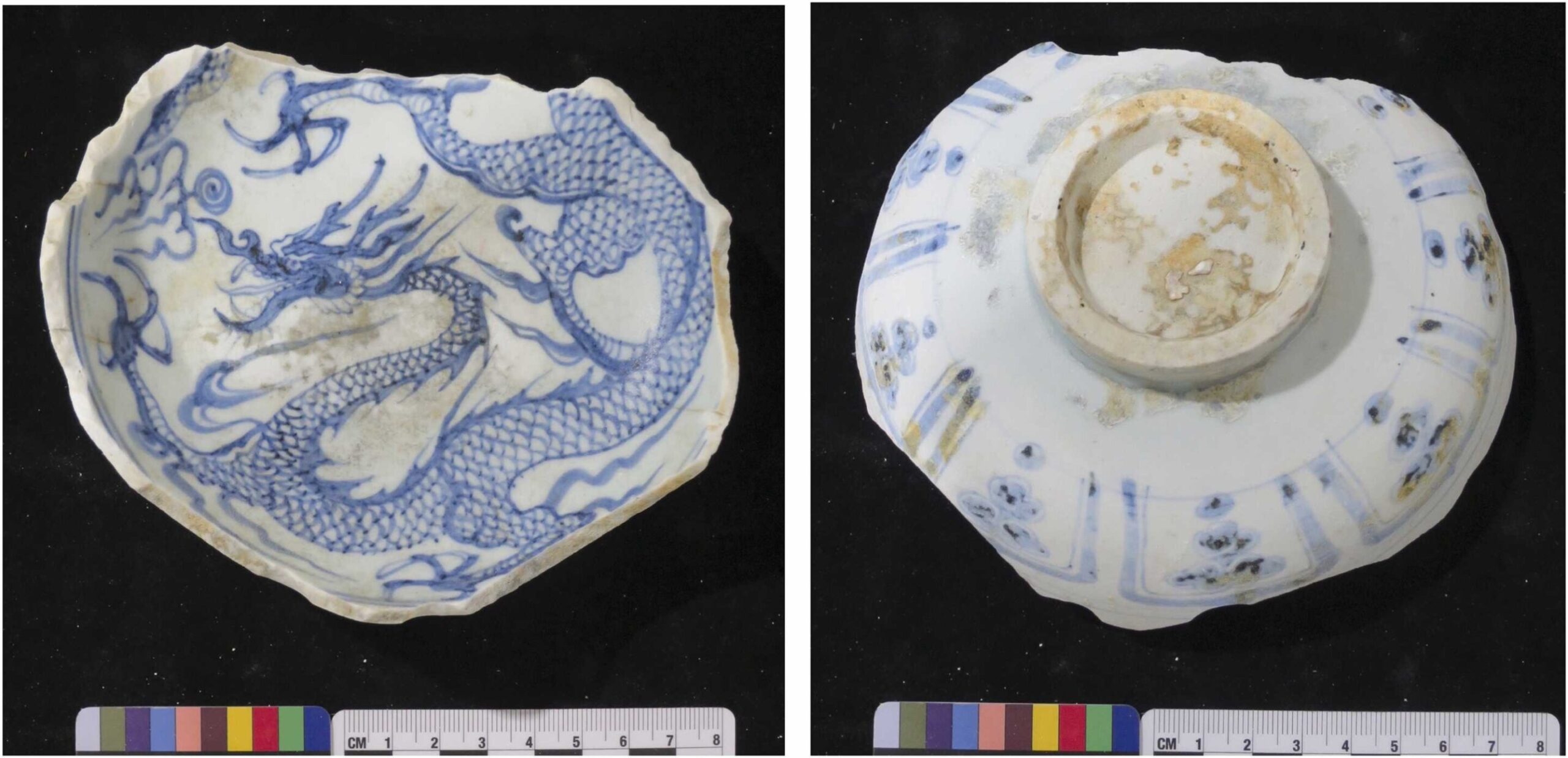

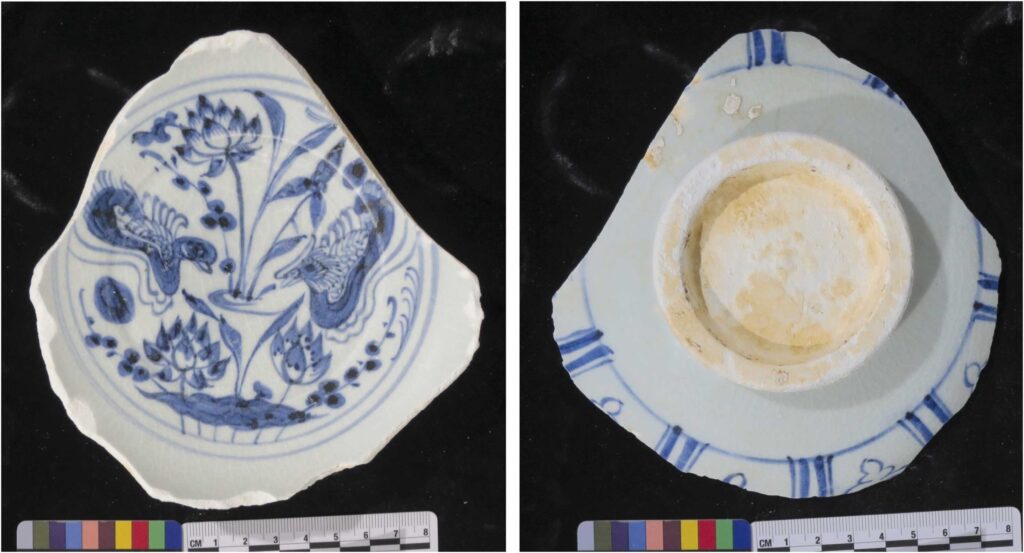

In a study published in the Journal of International Ceramic Studies, Dr. Michael Flecker of Heritage SG, a subsidiary of the Singapore National Heritage Board, presented a detailed analysis of the finds. The haul included 136 kilograms of rare blue-and-white porcelain—more than has been found on any other documented shipwreck. Alongside it were heavy stoneware jars, luminous Longquan celadon, and refined Shufu porcelain.

Each piece had once been shaped in a kiln, fired in intense heat, and prepared for trade. These were not random objects. They were cargo. Carefully selected goods meant for a market somewhere beyond the horizon.

Even broken, they held clues.

Dating the Deep Through Art

The challenge was to determine when the ship had made its final voyage. There was little left of the vessel itself, so the answers had to be found in the ceramics.

Dr. Flecker and his colleagues turned to decorative styles and kiln origins. Patterns can be surprisingly precise markers of time. Designs fall in and out of fashion. Political upheaval can halt production. Kilns open and close.

Among the most striking discoveries was a recurring motif inside the blue-and-white bowls: mandarin ducks on a lotus pond. This design, delicate and serene, had enjoyed popularity in China for only a short period. Production ceased when civil unrest disrupted the kilns.

That brief window proved invaluable. The motif helped date the ship’s last voyage to between 1340 and 1352, during the Yuan dynasty.

Suddenly, the wreck was no longer just an anonymous relic. It belonged to a specific era, a turbulent moment in history. It sailed during a time of upheaval, carrying goods crafted in kilns that would soon fall silent.

The sea had preserved a snapshot of trade frozen in time.

A Question of Destination

But another mystery remained. Where was the ship headed?

To answer this, Dr. Flecker employed what he described as a bit of detective work. The designs on many of the smaller bowls and vases closely matched ceramic fragments unearthed at Fort Canning and other archaeological sites in Singapore. The resemblance was not vague or coincidental. The styles were strikingly similar.

This suggested a strong local connection.

There was another crucial clue. In the 14th century, massive blue-and-white platters measuring 40 to 50 centimeters wide were highly popular in markets across India and the Middle East. If the ship had been bound for those distant markets, one would expect to find such oversized platters among its cargo.

Yet none were found on the Temasek Wreck. Every dish recovered measured under 35 centimeters.

The absence was telling.

Rather than being a vessel merely passing by on its way to the Indian Ocean, the ship appears to have been sailing directly toward Temasek. Singapore was not a waypoint. It was the destination.

A Port, Not a Village

The recovered ceramics tell a vivid story of life in 14th-century Temasek. According to Dr. Flecker, they provide insight into the utilitarian, elite, and ceremonial wares used by its inhabitants. This was not a place surviving on fish alone. It was a community that consumed fine porcelain, imported stoneware, and carefully crafted ceramics from distant kilns.

These goods had traveled hundreds, perhaps thousands, of kilometers by sea. They had been ordered, shipped, and expected. Trade routes connected Temasek to wider networks across the region.

For years, archaeological discoveries have chipped away at the image of early Singapore as a sleepy settlement. Excavations on land have revealed evidence of trade and habitation. But the Temasek Wreck offers something especially powerful: maritime proof.

The sea itself confirms the story.

Here was a merchant vessel loaded with luxury and everyday wares, sailing deliberately toward Temasek in the mid-1300s. It was not an accident of geography. It was commerce. It was demand. It was a thriving port participating in regional trade networks.

And when that ship sank, it left behind more than broken porcelain. It left behind evidence.

When Ceramics Rewrite History

There is something quietly profound about this discovery. No royal decree announced Temasek’s status as a trading hub. No grand monument proclaimed its importance. Instead, the truth emerged from mud, saltwater, and shards of clay.

The 136 kilograms of blue-and-white porcelain, the shimmering Longquan celadon, the elegant Shufu porcelain—these were not random belongings. They were goods in motion. They were part of an organized trade system. They were destined for buyers who valued and used them.

The Temasek Wreck now stands as the earliest known shipwreck in Singapore waters, and with it comes the strongest maritime evidence yet of Singapore’s role as a regional trading center long before 1819.

History is often shaped by what survives. In this case, it was ceramics that endured. Their patterns, sizes, and styles carried clues across seven centuries. From the motif of mandarin ducks to the absence of oversized platters, each detail helped reconstruct a journey cut short.

The sea tried to keep its secret. But the cargo remembered.

Why This Research Changes the Story

The significance of this research goes far beyond pottery. It challenges a long-held narrative about Singapore’s origins. Rather than emerging suddenly under colonial influence, the island already had deep connections to regional trade centuries earlier.

The Temasek Wreck demonstrates that in the mid-14th century, Singapore—then Temasek—was integrated into maritime trade networks. Ships sailed there with carefully selected cargo. Consumers awaited goods crafted in Chinese kilns. The port was active enough to justify significant shipments of valuable ceramics.

This discovery strengthens the understanding that Singapore’s story did not begin in 1819. It extends much further back, anchored in commerce, craftsmanship, and maritime exchange.

Most importantly, it reminds us that history is not fixed. It evolves with each new find, each shard lifted from the seabed. Beneath the waves off Singapore’s coast lay evidence that transforms how we see the past.

A ship sank sometime between 1340 and 1352. Its journey ended abruptly. Yet centuries later, its cargo has completed a different voyage—one that carries us toward a richer, more complex understanding of Singapore’s early identity.

The sea preserved the evidence. Archaeology uncovered it. And now, the story of Temasek shines through, no longer a quiet fishing village, but a vibrant trading hub alive with exchange, ambition, and connection.

Study Details

Michael Flecker, The Temasek Wreck ceramics cargo: Yuan blue-and-white porcelain, celadon and other ceramics found in Singapore waters, Journal of International Ceramic Studies (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.joics.2025.100013