For a long time, many people imagined early human societies as organized by strict, unbending rules — men doing one kind of work, women another, each role firmly fixed. But a new study is gently reshaping that picture, revealing a past that was both structured and surprisingly fluid.

Researchers from CNRS, working with an international team, have uncovered evidence that life in Neolithic Europe did not follow a rigid script. Their findings, published on February 16, 2026, in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology, suggest that while gendered roles certainly existed, they were not absolute. Even thousands of years ago, human identity and social life were more flexible than once assumed.

This discovery did not come from written records or ancient myths. It emerged from the quiet testimony of bones and burial grounds — the physical traces of lives once lived.

Listening to What the Skeletons Remember

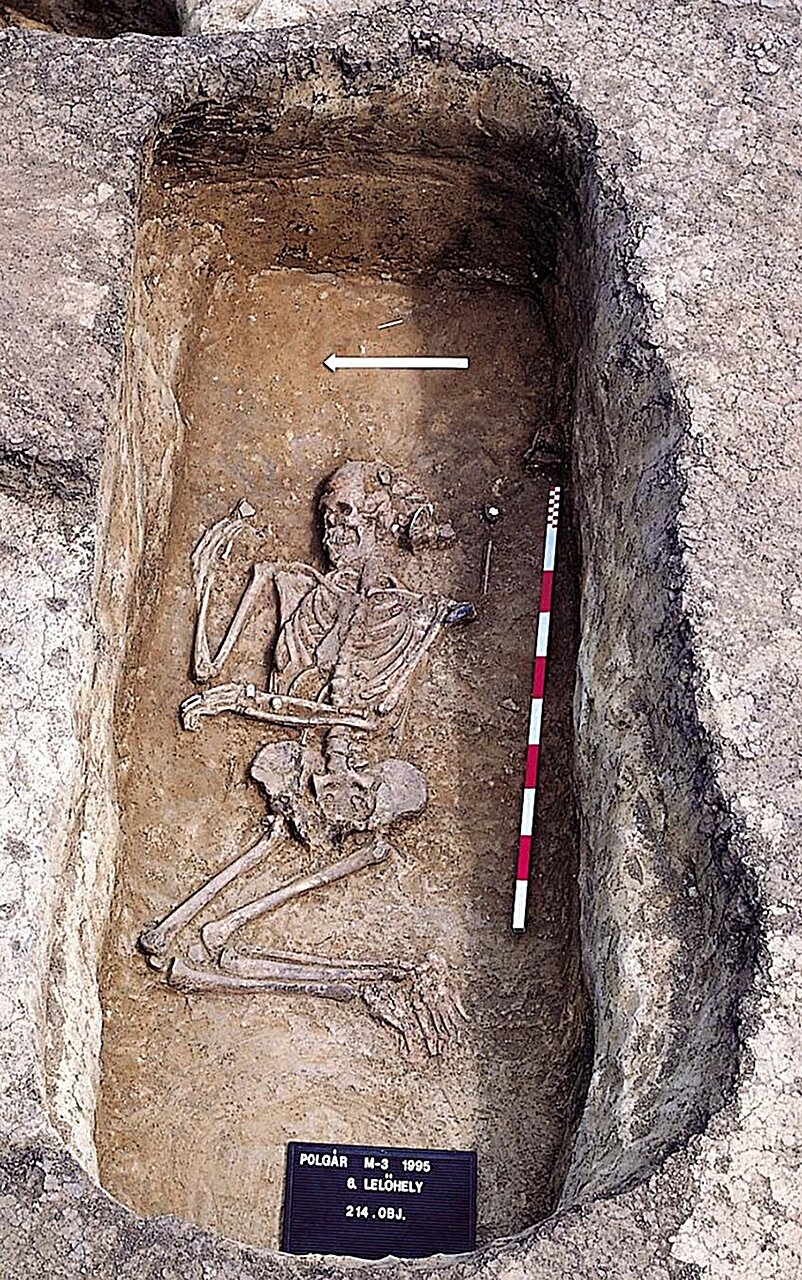

To understand how people lived more than seven thousand years ago, the research team turned to human remains from two archaeological sites in Hungary: Ferenci-hát, dated to 5300–5000 BCE, and Csőszhalom, dated to 4800–4600 BCE.

In total, they examined 125 adult skeletons. Each skeleton carried subtle physical records of daily life — marks that formed not at death, but through years of movement, effort, and repetition.

The researchers studied microtraumas at muscle attachment sites, which reveal how muscles were repeatedly used. They examined vertebral lesions, signs of intense physical strain placed on the spine. They also looked for markers of repeated postures, such as evidence that a person frequently knelt.

But bones alone cannot tell the whole story. The team also analyzed funerary practices — the ways people were buried, the positions of their bodies, and the objects placed beside them. These rituals reflect how the living understood social roles, identity, and status.

Together, physical strain and burial customs formed a combined record of how people worked, moved, and were remembered.

Bodies That Tell Stories of Work

Across both sites, a pattern emerged with striking consistency.

Male skeletons showed recurring lesions on the dominant arm — injuries or stress marks linked to powerful, repeated actions. These patterns are associated with activities such as throwing or working with stone and wood. Importantly, this same pattern has been observed broadly across prehistoric Europe, suggesting that such tasks were widely connected with men.

Female skeletons did not show these same dominant-arm stress patterns. This indicates that physical labor was indeed differentiated along gender lines. Men and women were not performing identical tasks.

Yet even in this evidence of division, the story does not end with strict separation. The bones reveal patterns — but patterns are not rules without exception.

The Silent Language of Burial

The site of Csőszhalom offered especially vivid insight into how society structured meaning around gender.

Here, burial customs were highly organized. Women were buried on their left side, while men were placed on their right. Many male graves included polished stone tools, objects that likely carried symbolic or practical significance. The arrangement suggests a clear social system that distinguished identities even in death.

Another revealing detail lay in the bones themselves. Markers of kneeling posture appeared far more frequently among male skeletons. This repeated physical stance points to specific activities — perhaps tasks performed in consistent positions — and possibly to a recognized social role tied to those activities.

Burial practices and skeletal evidence together suggest that certain forms of work and status were strongly associated with men. Society recognized these differences and expressed them in ritual.

Yet even here, in what appears to be a highly structured system, the researchers found something unexpected.

The One Burial That Changed the Story

Among the graves at Csőszhalom, one burial did not fit the established pattern.

A woman had been laid to rest with attributes typically associated with men — the same symbolic elements and burial treatment usually reserved for male individuals.

This single burial stands out not as an error, but as evidence. It shows that even within a socially structured system, exceptions were possible and accepted.

The society clearly recognized gendered roles. But it also made room, at least occasionally, for individuals who did not conform to typical expectations. The presence of this burial reveals that social identity was not entirely rigid. It could bend.

A Society Both Ordered and Flexible

Taken together, the findings paint a nuanced portrait of Neolithic society.

There were recognizable gender patterns. Physical labor often followed consistent divisions. Burial rituals reflected structured social meaning. These features align with broader patterns seen in other prehistoric European groups.

But alongside these patterns existed variation — and tolerance for that variation.

The presence of exceptions suggests that early communities did not operate under perfectly fixed categories. Instead, they navigated identity with a degree of complexity that feels deeply human. Roles could be defined without being absolute. Structure could exist alongside flexibility.

In other words, even thousands of years ago, societies were negotiating how individuals fit within shared norms — and sometimes allowing those norms to stretch.

Why This Research Matters

This study reshapes how we understand human social history. It shows that the idea of strictly binary, unchanging gender roles does not fully capture the lived reality of early agricultural communities.

By combining skeletal activity markers with funerary analysis, researchers have demonstrated that social organization in the Neolithic period was both patterned and adaptable. People recognized gendered roles, but they also allowed for complexity and individual variation.

This matters because it challenges simplified narratives about the past. Human societies have long been capable of nuance — capable of defining roles while also recognizing exceptions. The roots of social complexity did not emerge recently. They were present thousands of years ago, embedded in daily work, ritual, and identity.

The bones from Ferenci-hát and Csőszhalom do more than reveal how people lived. They reveal how people understood each other. And what they show is unmistakably human: a world structured by tradition, yet open enough to accommodate difference.

Even in the distant Neolithic, identity was never just one thing.

Study Details

Sébastien Villotte et al, Fixed and Fluid: The Two Faces of Gender Roles—A Combined Study of Activity Patterns and Burial Practices in the European Neolithic, American Journal of Biological Anthropology (2026). DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.70217