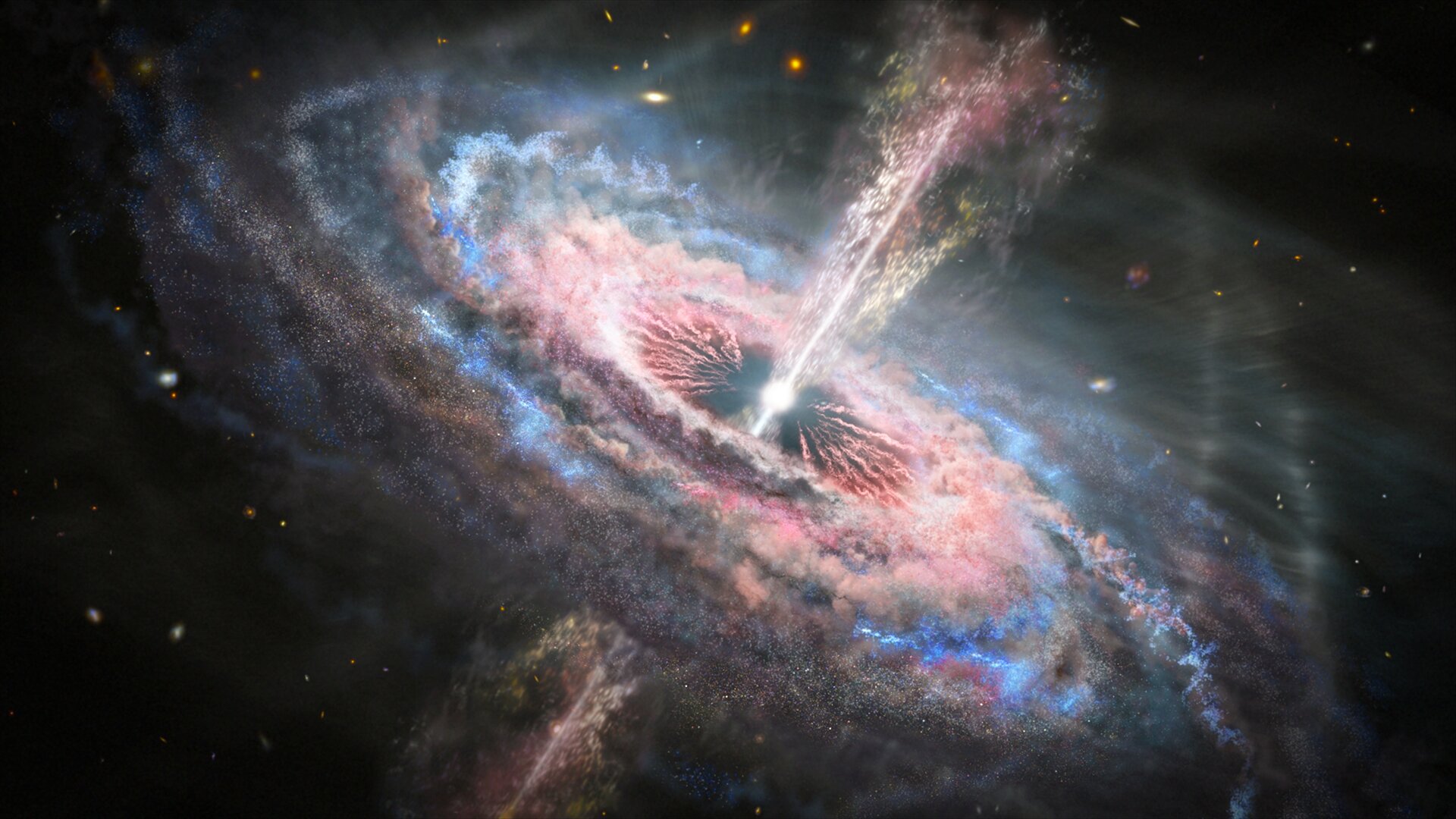

In the vast darkness of the early universe, something blazed so fiercely that it outshone entire galaxies. At the heart of a distant galaxy, a supermassive black hole gorged itself on gas and dust, unleashing a storm of radiation powerful enough to ripple across millions of light-years.

For generations, astronomers assumed that galaxies, separated by unimaginable distances, mostly lived independent lives. They formed stars, aged, and evolved in relative isolation. But new research led by Yongda Zhu, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Arizona Department of Astronomy and Steward Observatory, suggests a far more entangled story.

The findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, reveal that an extremely active black hole in one galaxy can slow the birth of stars not only in its own home, but also in neighboring galaxies millions of light-years away. It is a discovery that reframes the universe as something less like a collection of islands and more like a shared ecosystem.

Zhu calls this idea a “galaxy ecosystem.” In his view, an active black hole behaves like a dominant predator. It feeds. It radiates. And in doing so, it reshapes the environment around it.

The Brightest Monsters in the Universe

Black holes have long captured human imagination. Predicted in the early 1900s, they are among the most extreme objects known. Their gravity is so immense that even light cannot escape if it wanders too close.

Most galaxies are believed to harbor one at their center. A small subset are truly colossal, containing masses millions or even billions of times that of the sun. These are the supermassive black holes.

On their own, black holes are invisible. But when they begin actively devouring matter, they ignite. Gas and dust swirl into a blazing disk as they spiral inward, releasing staggering amounts of energy. During this luminous phase, they are known as quasars.

Some quasars shine with hundreds of trillions of times more energy than the sun, sometimes outshining the entire galaxy that hosts them. They are not subtle cosmic actors. They are cosmic beacons.

A Puzzle in the Early Universe

The story began with a mystery. Early observations from the James Webb Space Telescope seemed to show something unexpected. Around some enormous quasars in the young universe, astronomers saw fewer surrounding galaxies than anticipated.

This was strange. Large galaxies are typically found in dense clusters, not alone.

“We were puzzled,” Zhu recalled. For a moment, the team even joked about whether the powerful telescope was malfunctioning. But the answer, it turned out, was not about missing galaxies. It was about hidden ones.

Perhaps the galaxies were there—but difficult to detect.

The team realized that galaxies undergoing very recent star formation are easier to spot because young stars shine brightly. If something were suppressing new star growth, those galaxies might appear faint and harder to identify.

That “something,” they suspected, could be the quasar itself.

Testing the Galaxy Ecosystem

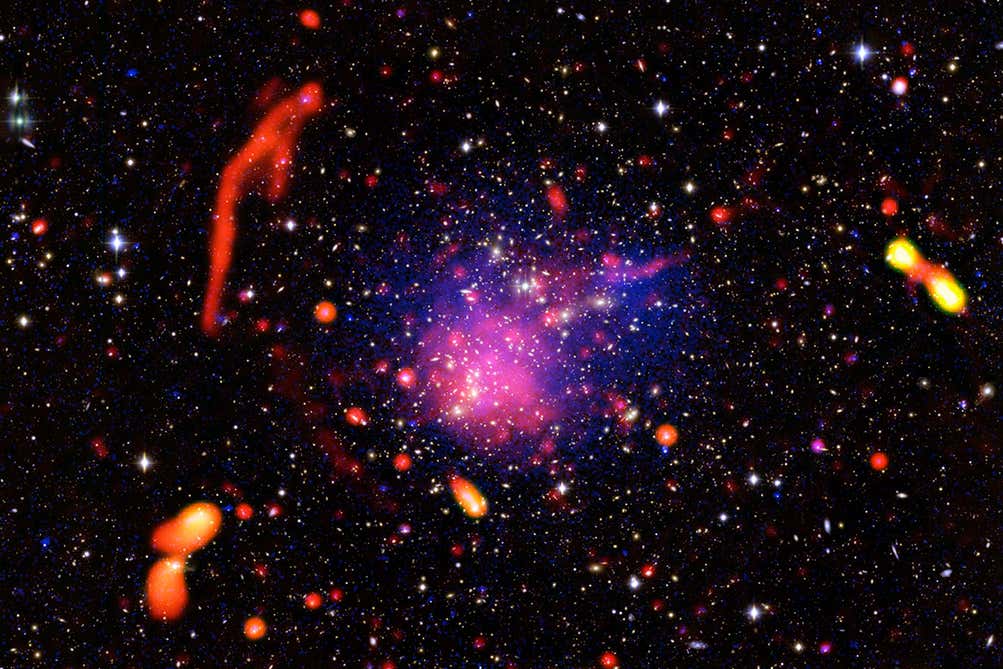

To explore this idea, the team focused on one of the most luminous quasars ever observed: J0100+2802. It is powered by a black hole roughly 12 billion times the mass of the sun. The light reaching Earth from this object comes from a time when the universe had not yet reached its 1-billion-year birthday.

Studying such a distant object is no small feat. By the time its light arrives here, the expansion of the universe has stretched its wavelengths deep into the infrared. Earlier telescopes struggled to detect these faint signals. But the James Webb Space Telescope, designed to see the universe in infrared light, made this investigation possible.

The researchers searched for emissions from O III, an ionized form of oxygen gas. This gas acts as a tracer of very recent star formation. When galaxies are actively forming new stars, O III emissions are strong. When star formation slows, the signal weakens.

By measuring the ratio of O III emission to ultraviolet light in galaxies surrounding J0100+2802, the team could determine whether star formation had been disrupted.

What they found was striking.

A Million-Light-Year Shadow

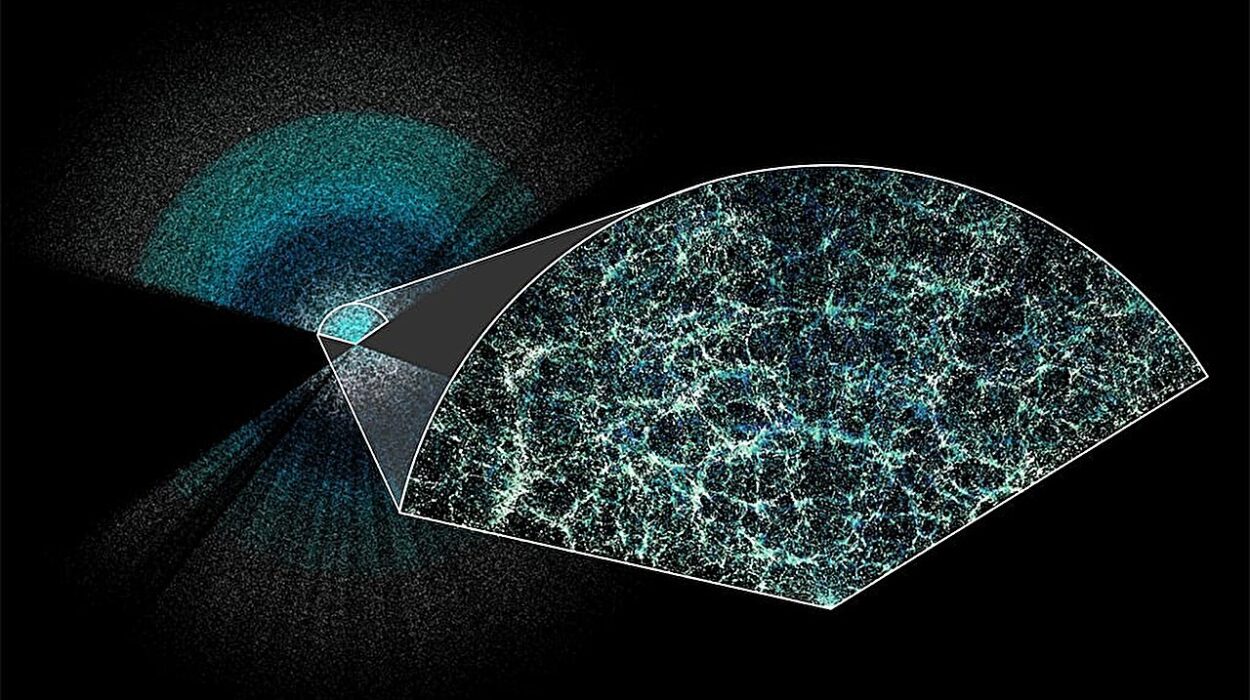

Galaxies within a radius of about one million light-years from the quasar showed noticeably weaker O III emissions relative to their ultraviolet light. The pattern suggested that their very recent star formation had been suppressed.

In simple terms, something had disturbed the delicate conditions required for stars to form.

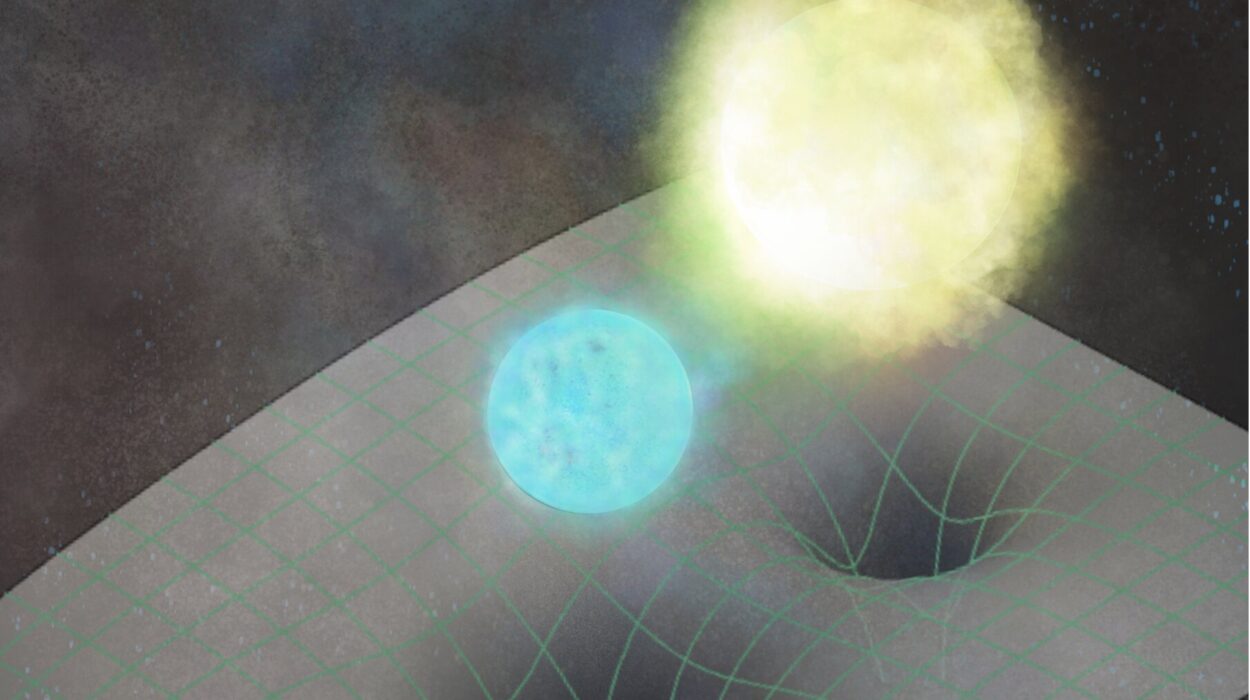

Stars are born inside vast clouds of cold molecular hydrogen. This gas acts as the raw fuel for star formation. Under the right conditions, gravity pulls the gas together until nuclear fusion ignites and a new star shines into existence.

But quasars are not gentle neighbors. During their active phase, they emit intense heat and radiation. According to Zhu, this radiation can split molecular hydrogen apart, disrupting the massive cold gas clouds that serve as stellar nurseries.

Without stable reservoirs of cold gas, star formation falters.

Scientists already knew that quasars could wreak havoc inside their own host galaxies, destroying the gas needed to form new stars. What had remained unclear was whether that destructive influence extended beyond the galaxy itself.

Now, for the first time, there is evidence that it does.

The radiation from a single, extremely luminous quasar appears capable of affecting galaxies across intergalactic distances, suppressing star growth over scales of at least a million light-years.

Seeing What No Telescope Could See Before

This discovery depended entirely on the capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope. Because the quasar’s light has been stretched into infrared wavelengths by cosmic expansion, earlier instruments could not clearly detect the faint signals needed for such detailed measurements.

Webb’s sensitivity allowed researchers to peer back more than 13 billion years, into an era when galaxies were young and rapidly evolving.

What they saw challenges a long-held assumption: that galaxies grow and change largely on their own.

Instead, the findings suggest that galaxy evolution may be shaped by interactions on vast scales. In the early universe, the brightest quasars may have acted as cosmic regulators, influencing which neighboring galaxies thrived and which struggled to form new stars.

Rethinking Our Own Origins

The implications ripple outward.

Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, likely once experienced its own quasar phase. Today, its central black hole is quiet. But in the distant past, it may have blazed just as fiercely.

If so, how did that active phase shape the Milky Way’s development? Did it influence neighboring galaxies? Did nearby quasars affect us?

The new findings do not yet answer these questions. But they open the door to asking them.

The research team now hopes to examine additional quasar fields to determine whether this phenomenon is widespread. They also aim to better understand how neighboring quasars interact and whether other factors may contribute to the suppression of star formation.

Why This Changes the Way We See the Universe

This research matters because it reshapes our understanding of how galaxies grow.

For decades, astronomers largely viewed galaxies as self-contained systems. But the evidence now points to something more interconnected. In the early universe, the brightest quasars may have influenced entire neighborhoods of galaxies, acting as cosmic predators that altered the course of stellar birth beyond their own borders.

Understanding this “galaxy ecosystem” helps scientists reconstruct the story of cosmic evolution. If supermassive black holes played a larger role than previously thought, then they were not just destructive forces at galactic centers. They were architects of structure on intergalactic scales.

And in that realization lies something profound. The universe is not merely a collection of distant, isolated worlds. It is a web of influence, where even across millions of light-years, a single hungry black hole can change the fate of countless stars yet to be born.

By uncovering this hidden connection, astronomers are not just studying distant quasars. They are piecing together the story of how galaxies—including our own—came to be.

Study Details

Yongda Zhu et al, Quasar Radiative Feedback May Suppress Galaxy Growth on Intergalactic Scales at z= 6.3, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ae1f8e