Far beyond the reach of ordinary sight, in a region of sky that has been quietly watched for years, something unexpected drifted into view. It wasn’t a star. It wasn’t a typical galaxy. It looked, astonishingly, like a cosmic jellyfish.

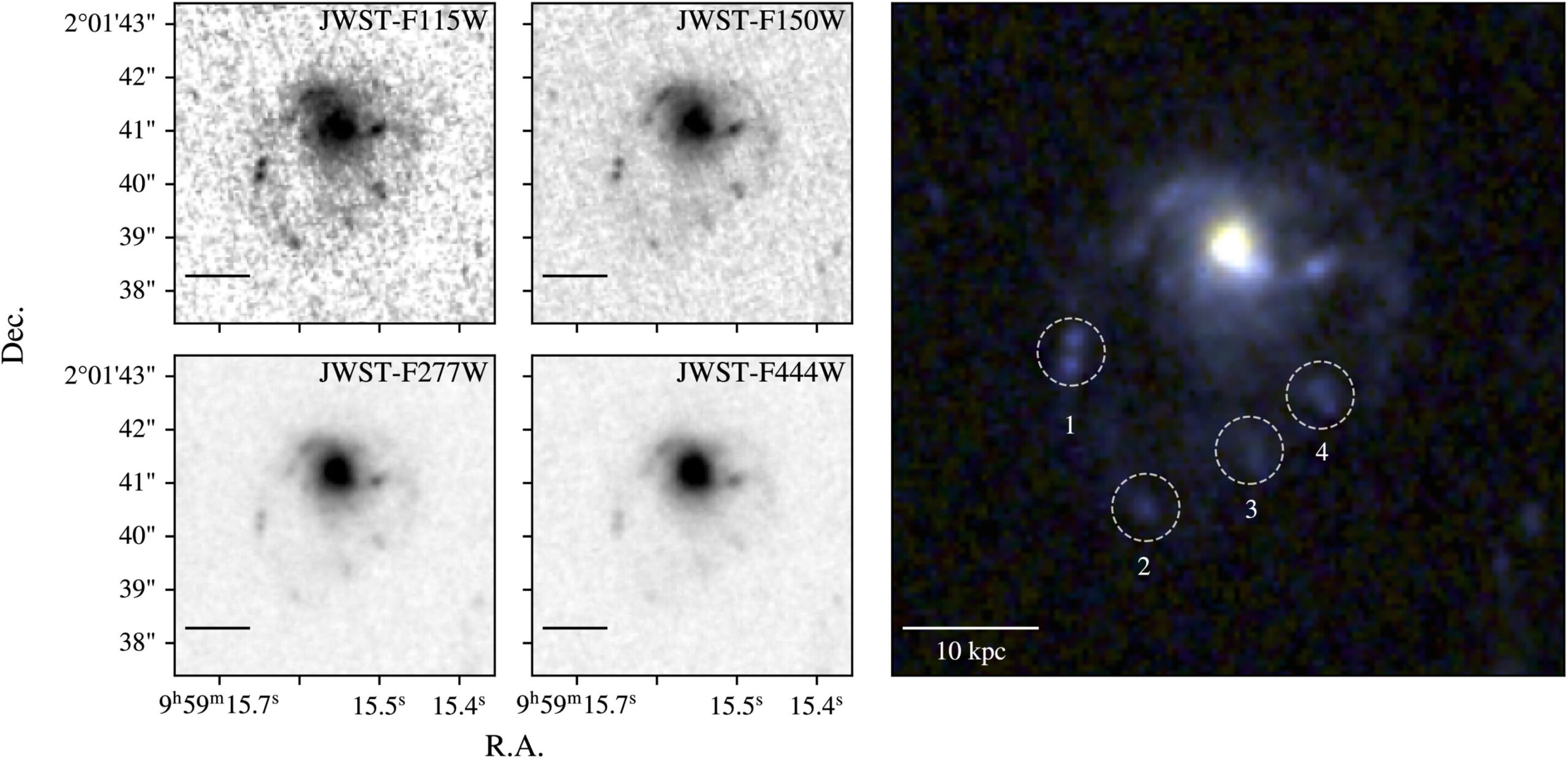

Astrophysicists at the University of Waterloo have observed the most distant jellyfish galaxy ever captured, a fragile-looking traveler from a time when the universe was only a fraction of its current age. Spotted in deep-space data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), this galaxy appears at a redshift of z = 1.156, meaning we are seeing it as it existed 8.5 billion years ago.

At that time, the universe was much younger. Galaxies were still growing, clusters were still assembling, and the cosmic landscape was thought to be less extreme than it is today. Yet this strange galaxy tells a different story.

A Sky Chosen for Its Silence

The discovery began in a carefully chosen patch of the sky known as the COSMOS field, short for the Cosmic Evolution Survey Deep field. Astronomers have long favored this region because it offers something rare: clarity.

It lies far from the plane of our own Milky Way, where fewer stars and less dust interfere with the view. It is visible from both hemispheres. There are no bright foreground objects blocking the scene. In other words, it is a window into the distant universe, wide open and remarkably clean.

Researchers were combing through a vast amount of JWST data from this well-studied region, hoping to spot jellyfish galaxies that had escaped detailed examination. Early in their search, something unusual stood out.

“We spotted a distant, undocumented jellyfish galaxy that sparked immediate interest,” said Dr. Ian Roberts, a Banting Postdoctoral Fellow at the Waterloo Centre for Astrophysics.

What they had found was not just another galaxy. It was a cosmic swimmer, trailing luminous tendrils behind it.

Why It Looks Like a Jellyfish

Jellyfish galaxies get their name from their appearance. They have a central disk—much like a normal galaxy—but behind them stretch long, tentacle-like streams.

These trails are formed by a dramatic process known as ram-pressure stripping.

As a galaxy speeds through the hot, dense gas of a galaxy cluster, that surrounding gas acts like a powerful wind. Imagine holding your hand out of a moving car window; the air pushes hard against it. In space, the effect is similar. The cluster’s gas pushes against the galaxy, stripping away its own gas and blowing it out the back. What remains are long, trailing streams.

In this newly observed galaxy, the researchers saw a normal-looking disk at the front. But behind it trailed bright blue knots—regions glowing with the light of very young stars.

Their color tells an important story. These stars are young enough that they must have formed in the stripped gas itself, outside the main body of the galaxy. In other words, the galaxy is not just losing material; it is giving birth to new stars in its wake.

It is a strange and beautiful contradiction: destruction and creation happening at the same time.

A Glimpse Into a Younger Universe

Finding a jellyfish galaxy is not unusual in the nearby universe. What makes this one extraordinary is its distance—and therefore its age.

At z = 1.156, we are looking back 8.5 billion years. This places the galaxy in an era when scientists believed galaxy clusters were still forming and evolving. The prevailing idea was that conditions in these clusters were not yet harsh enough to commonly produce ram-pressure stripping.

But this galaxy suggests otherwise.

Its presence implies that cluster environments were already severe enough to strip gas from galaxies at that early time. The cosmic wind was blowing hard long before many researchers expected it to.

The team’s findings, detailed in a paper titled “JWST Reveals a Candidate Jellyfish Galaxy at z = 1.156,” published in The Astrophysical Journal, challenge previous assumptions about the early universe.

Three Clues Hidden in the Tentacles

As researchers examined the galaxy more closely, three important implications emerged.

First, galaxy clusters at that time must have been harsh environments. The stripping process requires dense, energetic surroundings. The fact that this galaxy shows clear signs of ram-pressure stripping means those conditions were already in place.

Second, galaxy clusters may have been influencing and altering galaxies earlier than expected. If galaxies were being stripped of their gas, their ability to form new stars in their central regions would eventually decline. This process could dramatically reshape their evolution.

Third, these harsh conditions may have contributed to the large population of dead galaxies observed in galaxy clusters today. Dead galaxies are those that no longer actively form stars. If stripping was occurring 8.5 billion years ago, it may have helped build that quiet population much earlier than previously thought.

Taken together, these clues suggest that the universe’s large-scale structures were not gentle, slowly maturing systems. They were already dynamic, forceful, and transformative.

The Telescope That Made It Possible

This discovery would not have been possible without the sensitivity of the James Webb Space Telescope. Its deep-space observations allow astronomers to detect faint structures and subtle details in galaxies billions of light-years away.

In the COSMOS field data, the jellyfish galaxy’s trails and blue star-forming knots were clear enough to catch the researchers’ attention almost immediately.

But this may only be the beginning. The team has requested additional JWST observation time to probe the galaxy further. There are still mysteries hidden in those luminous trails.

How extensive is the stripping? How quickly is the gas being removed? How many stars are forming in the wake? Each question opens another window into the distant past.

A Cosmic Swimmer That Changes the Story

For decades, astronomers have pieced together a timeline of how galaxies and clusters formed and evolved. This jellyfish galaxy adds a new chapter.

It suggests that environmental transformation was already well underway 8.5 billion years ago. Galaxy clusters were not merely assembling; they were already powerful enough to reshape the galaxies within them.

The image of a galaxy racing through a dense cluster, shedding gas in glowing streams, is dramatic. But it is more than a beautiful picture. It is evidence. It is a fossil record written in light.

And it reminds us that the universe’s history is not always as tidy as our models predict.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it reshapes our understanding of when and how galaxies were transformed.

If ram-pressure stripping was active at z = 1.156, then the forces that shut down star formation in cluster galaxies were operating earlier than expected. That means galaxy clusters were mature and energetic sooner in cosmic history.

Understanding when galaxies lose their gas helps explain why so many galaxies in clusters today are no longer forming stars. It helps scientists trace the origin of the vast populations of dead galaxies we see in dense environments.

Most importantly, this discovery provides rare insight into the early universe. Observing a jellyfish galaxy so far away is like catching a fleeting moment in cosmic adolescence. It shows us that even then, galaxies were not isolated islands drifting peacefully. They were shaped, stripped, and transformed by their surroundings.

In the vast ocean of space, this distant jellyfish galaxy is more than a curiosity. It is a messenger from a younger universe, carrying evidence that cosmic forces were already at work, sculpting galaxies into the forms we see today.

Study Details

JWST Reveals a Candidate Jellyfish Galaxy at z = 1.156, The Astrophysical Journal (2026). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae3824.