Every star, no matter how brilliant, must one day fade. For stars like our Sun, that final act ends not in a fiery explosion but in quiet collapse. After billions of years of burning hydrogen into helium, the star exhausts its nuclear fuel, sheds its outer layers into space, and leaves behind a dense, dim ember—a white dwarf.

White dwarfs are among the most haunting objects in the universe: the compact remains of stars that once blazed with light and life. They are extraordinarily dense—a teaspoon of white dwarf matter would weigh several tons—and yet small enough to fit within the size of Earth. What makes them even more puzzling is their paradoxical nature: the heavier a white dwarf is, the smaller it becomes. Gravity squeezes these stellar remnants so tightly that the electrons inside can move no closer together, creating what physicists call degenerate matter.

These objects are not powered by fusion, the energy source of normal stars. Instead, they shine only because of the residual heat left over from their former lives, gradually cooling over billions of years until they fade into darkness. It’s a fate our own Sun will meet in about five billion years—a cosmic reminder that even stars have lifespans.

White Dwarfs in Binary Systems

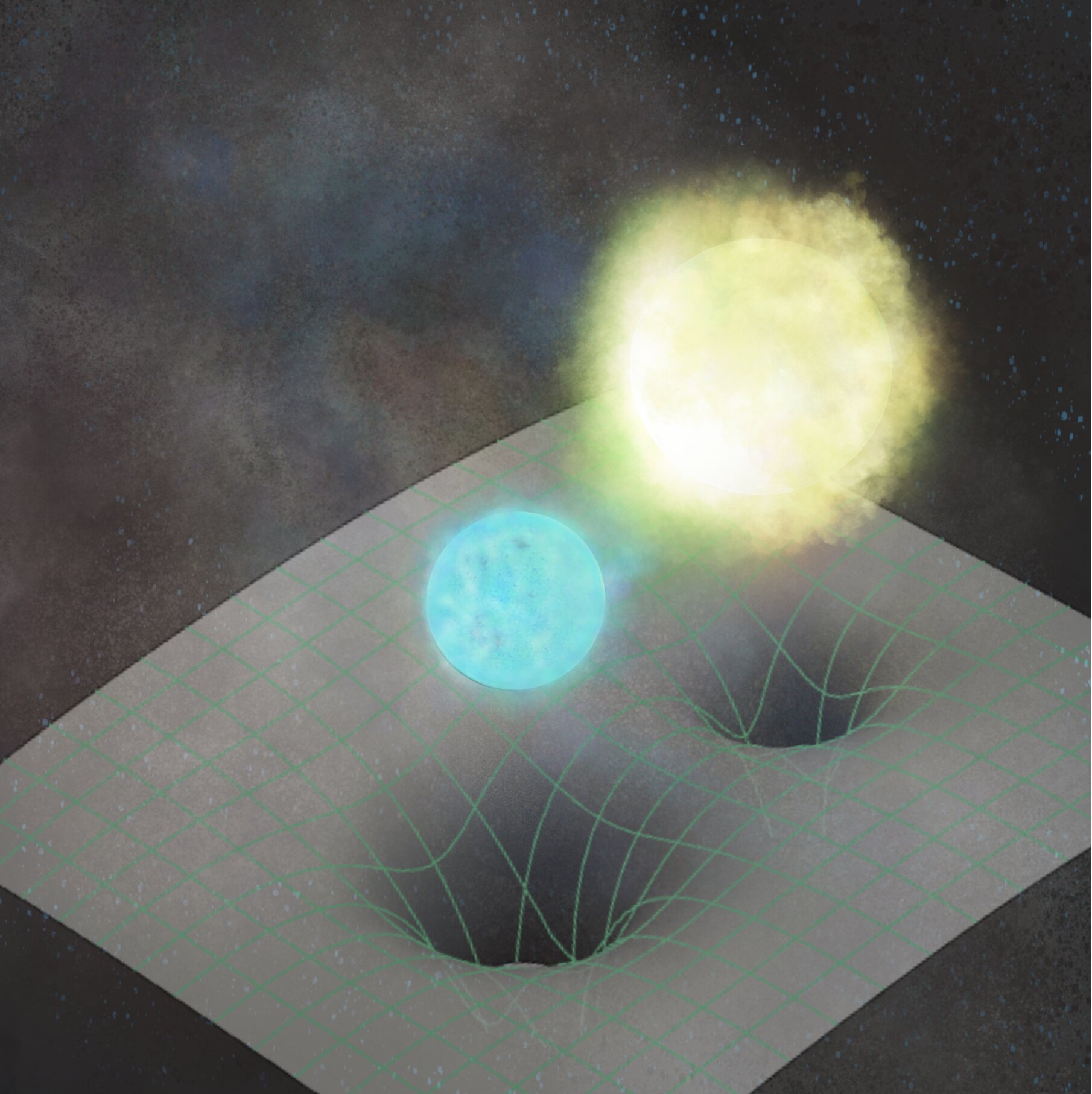

Although white dwarfs are remnants of death, they rarely exist alone. Many are found in binary systems, where two stars orbit a common center of gravity. These cosmic partnerships can be peaceful, but often they are anything but.

In some cases, a white dwarf steals material from its companion, igniting violent eruptions or even triggering catastrophic explosions known as Type Ia supernovae—the cosmic beacons used to measure the expansion of the universe. But even in systems without such fireworks, the gravitational intimacy between two stars can create surprising effects.

Most white dwarf pairs are ancient, cold, and stable, with surface temperatures around 4,000 Kelvin—cool by stellar standards. Yet astronomers have recently discovered a group of white dwarf binaries that defy expectations. These stars orbit each other in less than an hour—so close that they are practically brushing shoulders—and burn at searing temperatures between 10,000 and 30,000 Kelvin. Even more astonishingly, they are twice as large as theory predicts.

How could dead stars, long past their nuclear youth, grow hot and swollen again?

The Mystery of the Inflated White Dwarfs

This cosmic enigma caught the attention of Lucy Olivia McNeill and her research team at Kyoto University. Their curiosity led them to explore an idea borrowed from planetary science: tidal heating.

Tidal forces are the invisible hands of gravity that stretch and squeeze celestial bodies. On Earth, they lift our oceans twice a day as the Moon’s gravity tugs at the water. But in space, where objects are far more massive and orbits much tighter, these forces can have extraordinary effects.

McNeill’s team wondered whether such tides could be heating these white dwarfs—similar to how tidal heating explains the intense volcanic activity on Jupiter’s moon Io, or the inflated temperatures of “hot Jupiters,” the giant exoplanets that orbit perilously close to their stars.

“If tides can keep entire planets warm,” McNeill reasoned, “could they also rekindle the heat of dying stars?”

Rewriting the Rules of Stellar Physics

To answer this, the Kyoto team constructed a theoretical framework that could predict how much a white dwarf’s temperature might increase under the influence of its companion’s gravity. Their model was groundbreaking because it didn’t just describe one situation—it could be applied universally to white dwarf binaries across different ages, masses, and orbital distances.

When they ran the calculations, the results were stunning. Tidal forces, it turned out, can dramatically reshape the evolution of white dwarf pairs. The gravitational pull from a smaller, denser white dwarf can heat up and inflate its larger, cooler companion. This process raises the companion’s surface temperature to at least 10,000 Kelvin, far hotter than models predicted for ancient, cooling stars.

Even more intriguingly, this inflation means the white dwarfs are physically larger—about twice the expected size. Because of that, they begin to interact, or exchange matter, much sooner than scientists once believed. McNeill’s team found that these interactions could start when the stars are still three times farther apart than traditional theory suggested.

“We expected tidal heating would increase their temperatures,” McNeill explained, “but we were surprised to see how much the orbital period reduces for the oldest white dwarfs when their Roche lobes come into contact.”

In simpler terms, the tidal embrace of these stars tightens their orbits dramatically, speeding up the moment when they begin to share mass—a prelude to even more dramatic cosmic events.

When Gravity Becomes a Furnace

To visualize this, imagine two dead stars locked in a gravitational waltz, circling one another every forty minutes. Each orbit stretches and squeezes them, creating friction within their dense, compact interiors. That friction releases energy—heat that seeps to the surface, glowing like the last embers of a dying fire suddenly stirred to life.

Over time, this constant tug-of-war keeps the stars warmer and puffier than nature intended. And as they spiral closer together, they radiate gravitational waves—ripples in the fabric of spacetime predicted by Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Eventually, these binary white dwarfs will begin to interact directly, transferring mass from one to the other. This exchange can produce dazzling phenomena such as cataclysmic variables, where bursts of brightness erupt as matter crashes onto the white dwarf’s surface, or Type Ia supernovae, some of the most powerful explosions in the universe.

In essence, the quiet corpses of stars are brought back to life—if only briefly—by the relentless rhythm of gravity.

A New Lens on Cosmic Evolution

The Kyoto team’s research doesn’t just explain a long-standing mystery; it opens a new window into stellar evolution itself. Their model allows astronomers to trace how tidal forces have shaped these stars in the past and how they will continue to evolve in the future.

By applying this framework to different types of white dwarfs—especially carbon-oxygen ones, which are common remnants of Sun-like stars—the researchers hope to better understand the origins of Type Ia supernovae. These supernovae are vital cosmic tools: their consistent brightness makes them “standard candles” for measuring the expansion of the universe. But their exact formation process remains a subject of intense debate.

One key question is whether these explosions come from single-degenerate systems (a white dwarf and a normal star) or double-degenerate systems (two white dwarfs that merge). McNeill’s model could provide crucial evidence by revealing how tidal heating influences the likelihood of such mergers—and, ultimately, the conditions leading to supernova detonation.

The Human Element: Curiosity and the Cosmos

Behind every scientific discovery lies a spark of human wonder. McNeill’s team didn’t set out to rewrite stellar physics; they followed a simple question with enormous implications. Could the same physics that warms planets also rekindle the heat of dead stars?

That question bridges the intimate and the infinite—the same gravitational dance that shapes our tides also drives the evolution of stars light-years away. It’s a reminder that the universe operates under shared rules, weaving together the small and the grand into a single, elegant fabric.

Their work, published in The Astrophysical Journal, exemplifies how science thrives on curiosity. Even in an era of advanced telescopes and space missions, some of the universe’s deepest mysteries begin with an unexpected question—and the courage to pursue it.

The Legacy of Tidal Fire

White dwarfs are reminders of mortality, not just for stars but for everything that lives. Yet, as McNeill’s research shows, even in death there is motion, warmth, and transformation. The same gravitational forces that shaped their lives continue to sculpt their afterlives, creating beauty and complexity where we least expect it.

One day, billions of years from now, our own Sun will join their ranks. It, too, will shed its outer layers and shrink into a quiet white dwarf, orbiting alone or perhaps locked in a distant binary dance. And perhaps, through the tides of time, it will pulse again with a faint, enduring heat—a whisper of the life it once sustained.

A Universe That Never Truly Sleeps

In the end, McNeill and her colleagues remind us that even the universe’s so-called “dead” stars are far from lifeless. They pulse with hidden energy, shaped by invisible forces, their fates intertwined with the fabric of spacetime itself.

The cosmos is not a still and silent place—it is alive with motion, with tension, with transformation. And in the faint glow of a heated white dwarf, we can glimpse one of the universe’s most poetic truths: that nothing ever truly dies, it only changes form.

Stars may fade, but their stories continue—written in light, gravity, and time. And through the eyes of science, we are privileged to read them.

More information: Lucy O. McNeill et al, Tidal Heating in Detached Double White Dwarf Binaries, The Astrophysical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae045f