For decades, Mars has fascinated humanity more than any other planet. Its dusty red plains, whispering winds, and icy poles have fueled dreams of alien civilizations, flowing rivers, and even the possibility that life once thrived there. Each new discovery brings hope—and more questions. Did life ever exist on Mars? Could it still, somehow, persist beneath its frozen surface?

Recent research by Earth scientist Dr. Lonneke Roelofs from Utrecht University has brought us one step closer to understanding the forces that shape this enigmatic world. Her work doesn’t confirm Martian life—but it does uncover a process so dynamic, so alive in appearance, that it almost seems to breathe.

In her groundbreaking experiment, Roelofs found that blocks of frozen carbon dioxide—CO₂ ice—can carve gullies into Martian dunes, moving as though animated by an invisible hand. “It felt like I was watching the sandworms from the film Dune,” she said, describing the surreal sight. What she witnessed in a controlled laboratory experiment may explain one of the Red Planet’s most enduring mysteries: the strange, sinuous gullies that snake down its slopes.

The Martian Gully Mystery

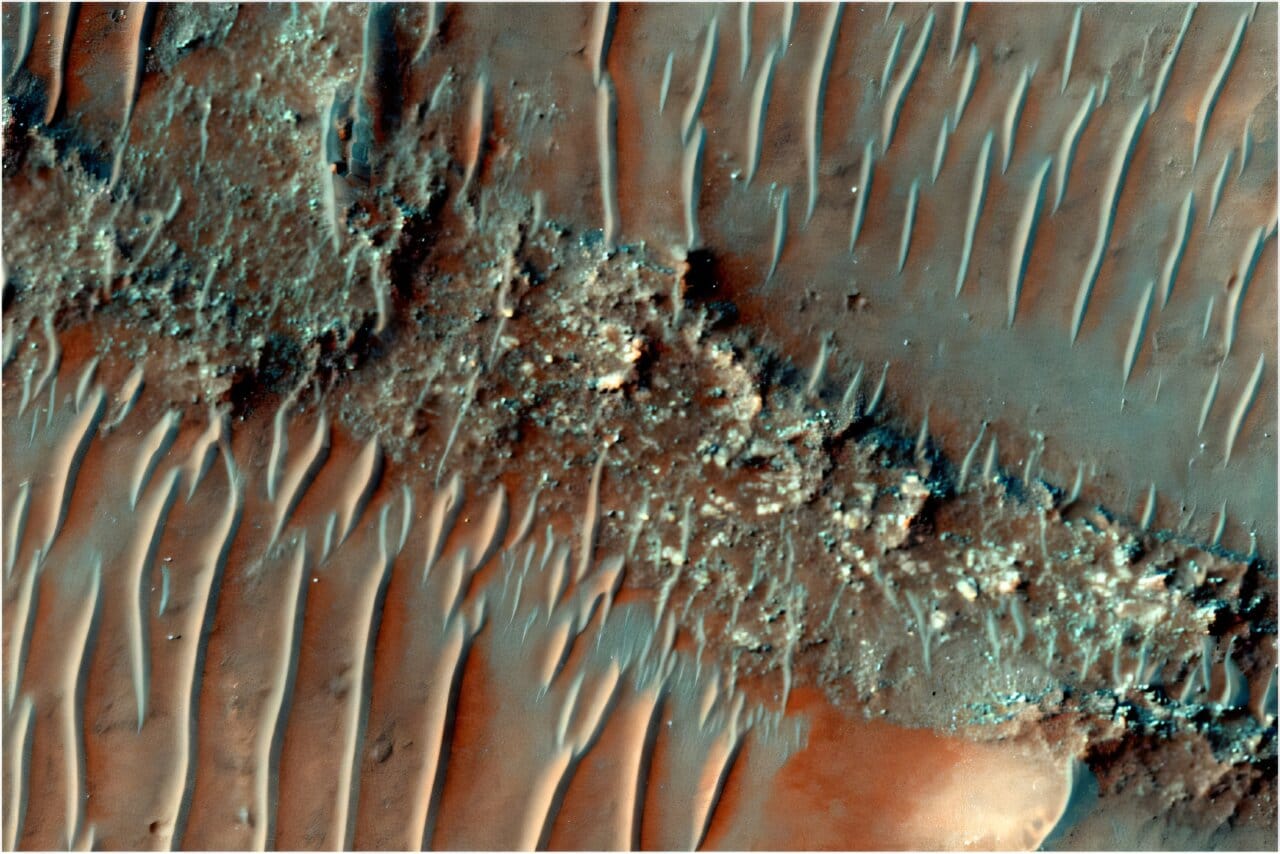

When spacecraft first captured images of these gullies on Mars, scientists were astonished. They resembled the erosion channels left by flowing water on Earth—deep cuts that descend along crater walls and sand dunes. The obvious conclusion was that water, the essential ingredient for life, might have flowed on Mars in the recent past.

But Mars is a cold, dry world. Its thin atmosphere allows liquid water to exist only fleetingly. How, then, could such features form?

Over time, other hypotheses emerged: perhaps frozen CO₂ or seasonal frost played a role. But the mechanism remained unclear—until Dr. Roelofs’ experiment offered a stunning explanation rooted in the physics of sublimation, the process where ice turns directly into gas without melting first.

The Dance of Ice and Sand

Mars, during its long winters, becomes a world encased in frost. When temperatures plummet to around –120°C, a layer of CO₂ ice (dry ice) forms across the planet’s southern dunes—sometimes reaching 70 centimeters thick.

As spring approaches and sunlight warms the dunes, the ice begins to weaken. Chunks of CO₂—some as large as a meter across—crack and break away, sliding down the sloping dunes. What happens next is unlike anything we see on Earth.

Because of Mars’s thin atmosphere and the stark contrast between warm sand and frigid ice, the underside of each ice block begins to sublimate rapidly. The CO₂ transforms into gas, expanding violently beneath the ice. “In our simulation, I saw how this high gas pressure blasts away the sand around the block in all directions,” explains Roelofs.

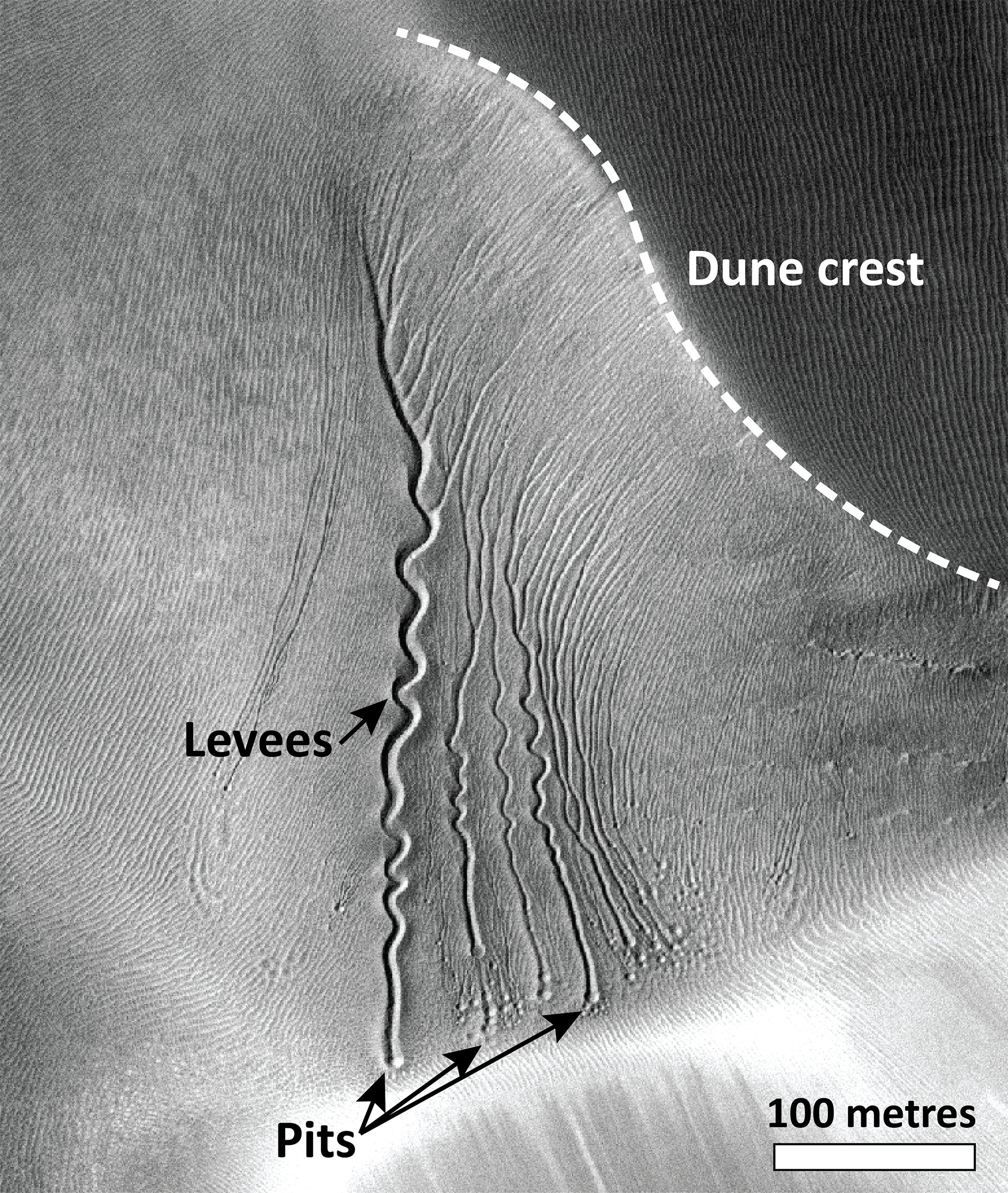

The result? The ice block doesn’t simply rest—it moves. It digs itself into the slope, carving a small hollow surrounded by ridges of displaced sand. As sublimation continues, the ice is pushed further down the slope, blasting and burrowing as it goes, leaving behind a deep, narrow gully that mirrors those seen on Mars.

“It looked as though the block was alive,” Roelofs recalls. “It burrowed into the sand like a mole—or like the sandworms from Dune. It looked very strange, almost mesmerizing.”

Recreating Mars on Earth

To test her theory, Roelofs collaborated with master’s student Simone Visschers and traveled to The Open University in Milton Keynes, England. There, inside a specially designed Mars chamber, they could recreate Martian conditions: freezing temperatures, low air pressure, and the fine-grained sands that mimic the planet’s surface.

“We tried out various things,” Roelofs explains. “We adjusted the steepness of the slope, dropped CO₂ ice blocks from different heights, and carefully observed how they behaved.”

After many trials, they found the perfect combination of slope angle and temperature. To their astonishment, the CO₂ blocks began to move on their own—digging, sliding, and plowing through the sand with uncanny precision.

It was a moment of revelation. What had seemed like an abstract theory now played out vividly before their eyes. These self-propelled ice blocks could indeed carve gullies, entirely without the help of liquid water.

The Alien Power of Sublimation

The process of sublimation—where a solid turns directly into gas—is well known on Earth. You can see it when dry ice “smokes” as it warms. But on Mars, sublimation becomes a force of transformation.

Because the Martian atmosphere is so thin—only about 1% as dense as Earth’s—even small temperature shifts cause CO₂ ice to vaporize explosively. A single kilogram of dry ice produces over 500 liters of gas, enough to send dust and sand flying.

As this gas erupts beneath an ice block, it lifts and pushes the block forward, gouging out a channel in the sand. The process repeats itself, step by step, as the block continues to sublimate, leaving behind a trench edged by miniature ridges. When the ice finally vanishes, what remains is a gully identical to those photographed on Mars by orbiters.

This discovery provides a new lens through which to view Martian landscapes. What once seemed to require running water may instead result from dry ice avalanches—a uniquely Martian phenomenon shaped by the planet’s frigid air and alien chemistry.

A World Shaped by Ice

Roelofs’s work adds to a growing understanding of Mars as a planet sculpted not by rivers but by frozen gases. Her earlier studies explored how CO₂ sublimation can also drive debris flows, carving deeper channels on crater walls.

Each new discovery reveals a world in motion—a planet that may seem lifeless, but whose surface is constantly shifting, reshaped by the delicate interplay of sunlight, temperature, and ice.

And yet, these processes may still hold echoes of something more profound. For many scientists, the search for Martian life is not only about microbes or fossils—it’s about understanding how nature behaves under conditions utterly different from Earth’s.

By studying these alien landscapes, researchers gain insights into how planets evolve, how atmospheres interact with surfaces, and even how life might adapt—or fail to adapt—under extreme conditions.

Why Mars Captivates Us

Why does Mars continue to hold such a grip on the human imagination? Partly, it’s because it’s our neighbor—close enough to study in detail, yet distant enough to remain mysterious. But more deeply, Mars sits near the “habitable zone”—the region around the Sun where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist. That tantalizing possibility makes Mars a natural laboratory for studying life’s potential beyond Earth.

“Mars is our nearest neighbor,” Roelofs says. “It is the only rocky planet close to the ‘green zone’ of our solar system. Questions about the origin of life, and possible extraterrestrial life, could therefore be solved here.”

For humanity, Mars represents both a mirror and a mystery. It reflects our own planet’s history—its dry riverbeds once filled with water, its polar caps of ice—and yet it reminds us how fragile life truly is.

Lessons for Earth

The beauty of planetary science is that in studying other worlds, we often learn more about our own. By understanding how dunes shift on Mars, scientists can refine models of desert formation on Earth. By studying sublimation-driven gullies, we can better predict how frozen landscapes change under different climates.

As Roelofs explains, “Conducting research into the formation of landscape structures of other planets is a way of stepping outside the frameworks used to think about Earth. This allows you to pose slightly different questions, which in turn can deliver new insights for processes here on our planet.”

In other words, Mars is not just a distant curiosity—it is a teacher. Its strange, frozen dunes and explosive ice movements remind us that the laws of nature are both universal and endlessly creative.

The Wonder of a Living-Looking Planet

Though there is still no conclusive evidence that life ever existed on Mars, the world Roelofs studies feels alive in its own right. Its landscapes move and breathe with the rhythm of seasons. Its surface bears the marks of invisible forces, sculpting and reshaping it as though guided by intent.

When Dr. Lonneke Roelofs watched her CO₂ ice block “crawl” across simulated Martian sand, she glimpsed a world that defies expectations—a planet where even in the absence of life, motion and transformation persist.

In that sense, Mars teaches us something profound: life is not the only source of beauty, creativity, or change. Even without biology, the universe creates wonders that mimic the pulse of living systems.

Perhaps, in watching the “sandworms” of Mars dig their silent paths through alien dunes, we are witnessing something greater than geology. We are watching the cosmos itself—restless, inventive, and ever-evolving—continuing its ceaseless work of shaping worlds.

The Continuing Quest

The story of Mars is far from over. Each discovery deepens our connection to this red world, blurring the line between the familiar and the alien. As robotic explorers continue to roam its surface and orbiters scan its skies, the question that has haunted humanity for centuries remains: Did life ever find a foothold there?

For now, the answer is still hidden beneath layers of dust and ice. But thanks to the work of scientists like Lonneke Roelofs, we are learning to read Mars’s language—to interpret the whispers of its winds, the trails carved by its ice, and the stories etched in its sands.

And whether or not we ever find life on Mars, the search itself is a reflection of our own vitality. It is life—on Earth—reaching out across the void, asking the oldest question of all: Are we alone?

Until that answer arrives, the dunes of Mars will continue their silent motion, sculpted by forces unseen, whispering the secrets of a planet that still refuses to be forgotten.

More information: Lonneke Roelofs et al, Sliding and Burrowing Blocks of CO2 Create Sinuous “Linear Dune Gullies” on Martian Dunes by Explosive Sublimation‐Induced Particle Transport, Geophysical Research Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1029/2024gl112860