In a windswept, frozen desert 225 million kilometers away, Mars hides a secret beneath its dusty red skin—a secret that’s reshaping everything we thought we knew about the planet’s ancient past.

A sweeping new study has revealed more than 15,000 kilometers of ancient riverbeds etched across a region of Mars known as Noachis Terra, located in the planet’s southern highlands. These winding formations—remnants of long-vanished rivers—tell a vivid story of a planet that may once have been alive with the sound of flowing water.

The findings, unveiled today at the Royal Astronomical Society’s National Astronomy Meeting 2025 in Durham, suggest that Mars was not the cold, arid world of brief and rare water events as once believed. Instead, it may have been warmer, wetter, and much more Earth-like, with rainfall-fed river systems carving paths across its ancient surface.

And most remarkably, these river networks seem to have persisted for millions of years—a clue that Mars, during its distant past, may have harbored the right conditions to support life.

Rivers in Stone: The Silent Story of Noachis Terra

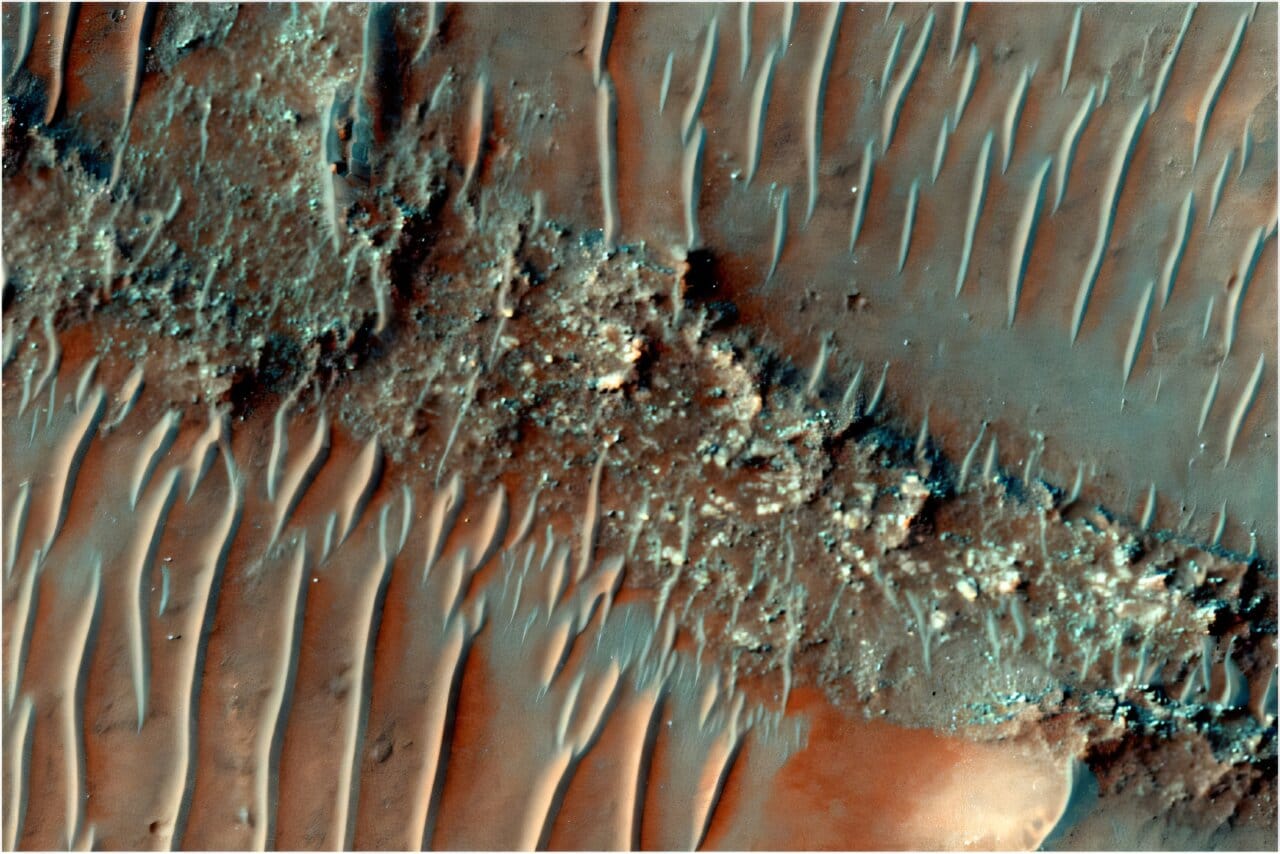

To understand how scientists unlocked this watery chapter in Martian history, you need to know about a special kind of landform called fluvial sinuous ridges, or more evocatively, inverted channels.

Here on Earth, we’re used to seeing rivers as depressions in the ground. But on Mars, the opposite often holds true. Over billions of years, soft sediments surrounding ancient rivers have eroded away, while the sediment that once filled the riverbeds—now hardened into rock—has remained. What’s left behind is a raised, snake-like ridge that traces the path where water once flowed.

These are the fingerprints of ancient Martian rivers. And in Noachis Terra, there are thousands of them.

“Noachis Terra hasn’t received as much attention as some other regions of Mars because it lacks the dramatic valley networks that have traditionally been used to infer rainfall,” said Adam Losekoot, the Ph.D. researcher from The Open University who led the study. “But when we looked closer using new tools, a very different story started to emerge.”

Using data from three of NASA’s most powerful orbiting instruments—the Context Camera (CTX), the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA), and the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE)—Losekoot and his team began piecing together an immense map of the region’s ridges.

What they found stunned them.

Some ridges were isolated fragments, like broken bones from a forgotten world. Others formed interconnected river systems extending for hundreds of kilometers, some rising dozens of meters above the surrounding terrain—massive, unmistakable signatures of long-lived fluvial activity.

A World Not of Ice, But of Rain

These ancient rivers date back to a time scientists call the Noachian-Hesperian transition, around 3.7 billion years ago. This was an era of dramatic change on Mars—a time when the planet’s climate was shifting, its volcanic activity simmering, and surface water becoming increasingly rare.

Until now, many scientists believed that during this period, Mars was already slipping into its cold, dry fate. Any water that did exist, they argued, likely came from sporadic bursts of melting beneath thick ice sheets, perhaps triggered by volcanic eruptions or asteroid impacts.

But the new findings challenge that bleak vision.

The size, shape, and spatial spread of the inverted channels in Noachis Terra strongly point to precipitation—yes, rainfall—as the most likely source of the water.

“To get river systems this widespread, this complex, and this interconnected, you need a climate that can sustain surface water for long periods,” said Losekoot. “That means temperatures warm enough for liquid water, and an atmosphere thick enough to support rainfall.”

This insight throws a wrench into the idea that Mars was mostly frozen with only rare, short-lived warm spells. Instead, it suggests that Mars had a stable water cycle—complete with clouds, rain, and long-flowing rivers—at least in some regions and for significant stretches of time.

Mars, the Time Capsule

Part of what makes this discovery so remarkable is the preservation of these features. Mars has no plate tectonics, no oceans to wash away its past, no forests or bustling biosphere to overgrow or obliterate what came before. Its surface is a museum of planetary history, a frozen canvas largely unchanged for billions of years.

“Studying Mars, particularly an underexplored region like Noachis Terra, is really exciting because it’s an environment which has been largely unchanged for billions of years,” said Losekoot. “It’s a time capsule that records fundamental geological processes in a way that just isn’t possible here on Earth.”

In Noachis Terra, the planet’s surface has preserved clues to a time when Mars may have been not only geologically active—but climatically complex and hydrologically alive.

The ridges are more than just rock formations. They are stories carved by time and water, telling of a planet that once ran with rivers across its ancient skin.

What It Means for Life on Mars

The implications of this study ripple far beyond geology.

If rainfall fed rivers once flowed freely across Mars for long periods, it suggests that habitable conditions may have been widespread and persistent. That’s a key consideration in the search for past life.

In contrast to brief, localized melt events—like sudden floods that disappear in days or weeks—long-term river systems offer a stable, nurturing environment where microbial life could emerge, evolve, and possibly thrive.

“Noachis Terra might have been a cradle of life,” said Losekoot. “And we’ve only just begun to explore it.”

As missions like NASA’s Perseverance Rover continue their hunt for biosignatures elsewhere on Mars, discoveries like these will help guide future landers and explorers. Perhaps, one day, we’ll return to Noachis Terra—not just to study its past—but to search its rocks for ancient Martian fossils.

A New Chapter in Mars’ Story

In just a few decades, our view of Mars has transformed—from a dead, dusty world to a planet with a rich, dynamic history. Now, thanks to the tireless work of planetary scientists and high-resolution space technology, we’re seeing deeper and further into that history than ever before.

Losekoot’s work opens a new chapter in the story of Mars—not one of cold desolation, but of water, warmth, and the possibility of life.

As we stand on the edge of a new space age—one in which humans may someday set foot on the Red Planet—discoveries like this remind us why we explore: to uncover not just facts and figures, but the living story of a once-blue world that may, in some forgotten eon, have looked a little more like home.

More information: The Fluvial History of Noachis Terra, Mars, conference.astro.dur.ac.uk/eve … 7/contributions/607/