The night sky has always been humanity’s oldest storybook—etched not in ink, but in starlight. Long before telescopes or space probes, early astronomers gazed upward with nothing more than their eyes and curiosity, recording celestial wonders in poetry, chronicles, and sacred texts. Now, centuries later, these ancient words are once again illuminating the heavens.

A recent study has revealed two Arabic manuscripts that may describe the appearance of two of the most famous supernovae ever witnessed from Earth—one in the year 1006 AD and another in 1181 AD. These discoveries not only add to the historical record of astronomical observation but also highlight the remarkable sophistication of early Arab astronomers. Their keen eyes and poetic words have preserved cosmic events that modern science continues to unravel.

The Forgotten Record Keepers of the Cosmos

It’s easy to think of astronomy as a purely modern science, defined by telescopes, satellites, and digital sensors. Yet, centuries before such technology, the night sky was humanity’s universal map and clock. In the medieval Islamic world, astronomy flourished as scholars sought to understand the motions of the heavens—not just for navigation or prayer times, but out of sheer intellectual wonder.

Arab astronomers were meticulous observers. They charted stars, recorded eclipses, and noted “new stars” that appeared without warning—what we now call novae and supernovae. These records were not isolated notes but part of a continuous tradition of sky-watching that stretched from the deserts of Arabia to the courts of Baghdad, Cairo, and Damascus.

The rediscovery of two Arabic texts referencing ancient supernovae brings new depth to that legacy, showing that even in an age of poetry and parchment, the human drive to understand the cosmos burned as bright as the stars themselves.

The Shining Ghost of 1181 AD

The first of the newly rediscovered references concerns the supernova of 1181 AD, known to astronomers today as SN 1181. Until recently, this event was documented only in Chinese and Japanese records, leaving gaps in our understanding of where exactly it appeared and how bright it was.

That changed with the discovery of a poetic verse written by the Arab scholar Ibn Sanāʾ al-Mulk. His poem, composed to honor the legendary Muslim leader Saladin, contains a striking celestial metaphor:

“I see how everything on the surface of Earth has increased in number thanks to your justice; now even the stars in the sky have increased in number. The sky adorned itself with a star; nay, it smiled through it, because whoever is delighted by a delightful thing smiles.”

The imagery is rich and symbolic, but also specific. The mention of a “new star” appearing in the heavens—bright enough to catch notice—aligns with what astronomers now know of SN 1181, a supernova that briefly added a brilliant point of light to the constellation Cassiopeia. In Arabic tradition, this region of the sky was called Al-Kaff al-Khadib, or “The Henna-Painted Hand.”

Modern researchers believe the poem was written between 1181 and 1182, when Saladin and his brother were both present in Cairo—exactly when SN 1181 would have been visible. What’s more, the poem’s tone suggests the star was unusually bright, perhaps shining at magnitude 0—comparable to Saturn or brighter than any ordinary star in Cassiopeia.

For astronomers today, this new evidence helps narrow down the likely position of SN 1181 in the night sky, a detail that remains crucial because its exact remnant—what’s left behind after the explosion—has been a matter of debate for centuries.

The Blazing Wonder of 1006 AD

The second text concerns a far older event: the spectacular supernova of 1006 AD. Known as SN 1006, it is perhaps the brightest stellar explosion ever recorded by humans. Contemporary accounts describe it as a star so luminous it could cast shadows and be seen in daylight.

The new Arabic source comes from the historian Ahmad ibn ʿAlī al-Maqrīzī, who lived in Egypt between 1364 and 1442. In his writings, he recounts a celestial event that accompanied the revolt of Abū Rakwah:

“When Abū Rakwah rose in revolt, a star with a tail appeared. It shone like the moon with brightness and gleam and its light strengthened and increased so long as Abū Rakwah’s cause got on well and became ominous. This star remained some months; then its light dwindled and its gleam faded away.”

The description is vivid—and while al-Maqrīzī uses the term kawkab (meaning star or celestial object), it matches other accounts of SN 1006 in duration, brightness, and behavior. The mention of a “tail” might suggest a comet, but few comets remain visible for several months, and none would shine with such brilliance.

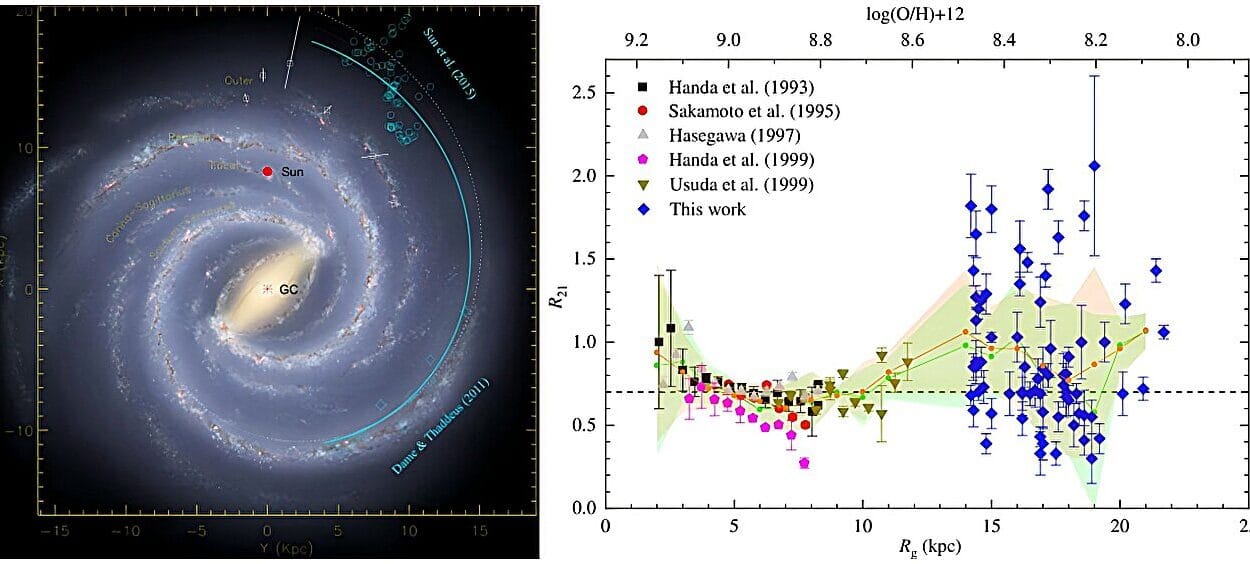

SN 1006 appeared near the constellations Lupus and Hydra, deep in the southern sky—visible only from latitudes south of 40 degrees. This meant that much of Europe missed the event, but it was clearly visible to observers across Arabia, Egypt, and East Asia. For those who saw it, it must have been both breathtaking and unsettling—a sudden, ghostly new sun blazing in the heavens.

The Scholars Behind the Discovery

The recent rediscovery of these texts was not the result of a grand expedition but of patient, meticulous scholarship. Jens Fischer of the University of Münster first identified Ibn Sanāʾ al-Mulk’s poem as describing SN 1181, re-dating the manuscript to align with Saladin’s lifetime. Meanwhile, Heinz Halm of the University of Tübingen found the passage about SN 1006 in al-Maqrīzī’s writings, recognizing its possible astronomical significance.

Both findings were, in a sense, serendipitous. Yet they remind us how intertwined art, history, and science can be. A poem written to honor a ruler, or a chronicle describing a rebellion, can become an astronomical record—a bridge between emotion and evidence, poetry and physics.

As Ralph Neuhäuser, an astrophysicist at the University of Jena, notes: “For SN 1181, there were only Chinese and Japanese records known before, so any new reports with astronomical details are important.” The Arabic poem, he adds, provides clues about the star’s brightness and position that could finally help identify its true remnant in the sky.

The Science Behind the Stars

What exactly is a supernova? In scientific terms, it’s the explosive death of a star—a brief, brilliant eruption in which a star releases more energy in a few weeks than the Sun will emit in its entire ten-billion-year lifetime.

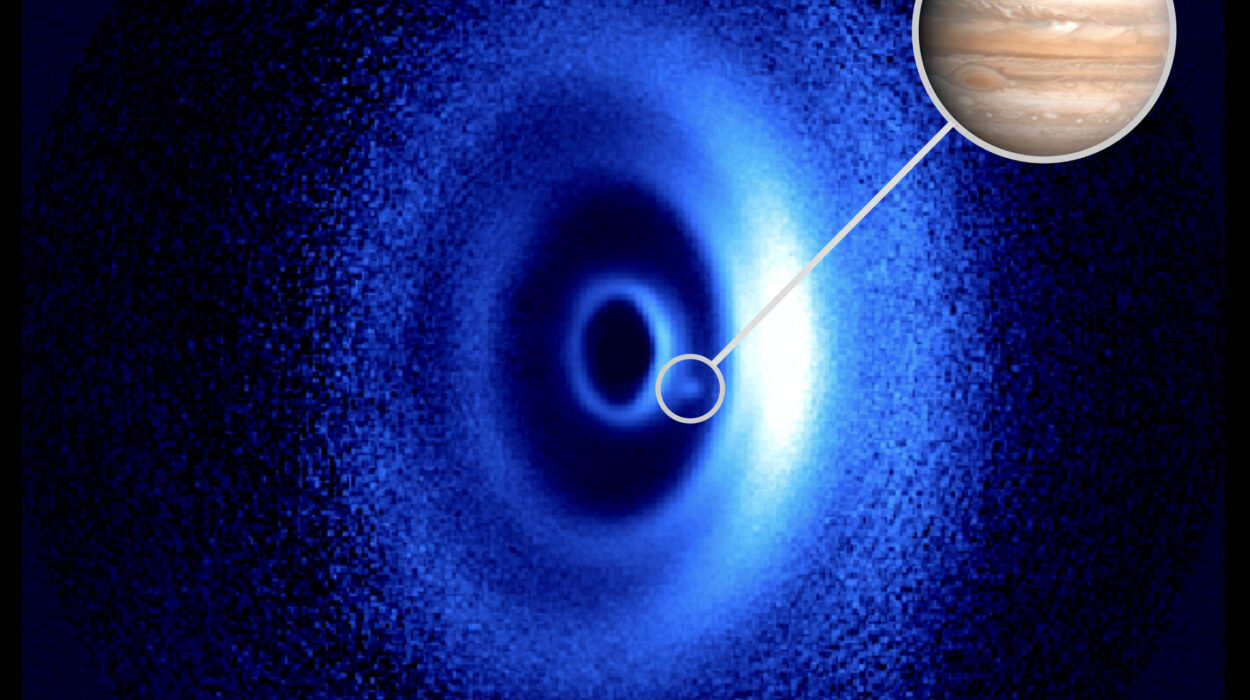

There are several kinds of supernovae, but both SN 1006 and SN 1181 are thought to have been Type Ia or Iax events. These occur when a dense, dying star known as a white dwarf steals material from a nearby companion star until it can no longer sustain itself and collapses in a catastrophic blast.

Supernovae are cosmic recyclers. They forge heavy elements—carbon, iron, gold, and more—and scatter them across space, seeding new stars, planets, and eventually, life. Every atom of iron in your blood and calcium in your bones was born in a star that once ended in such a brilliant death.

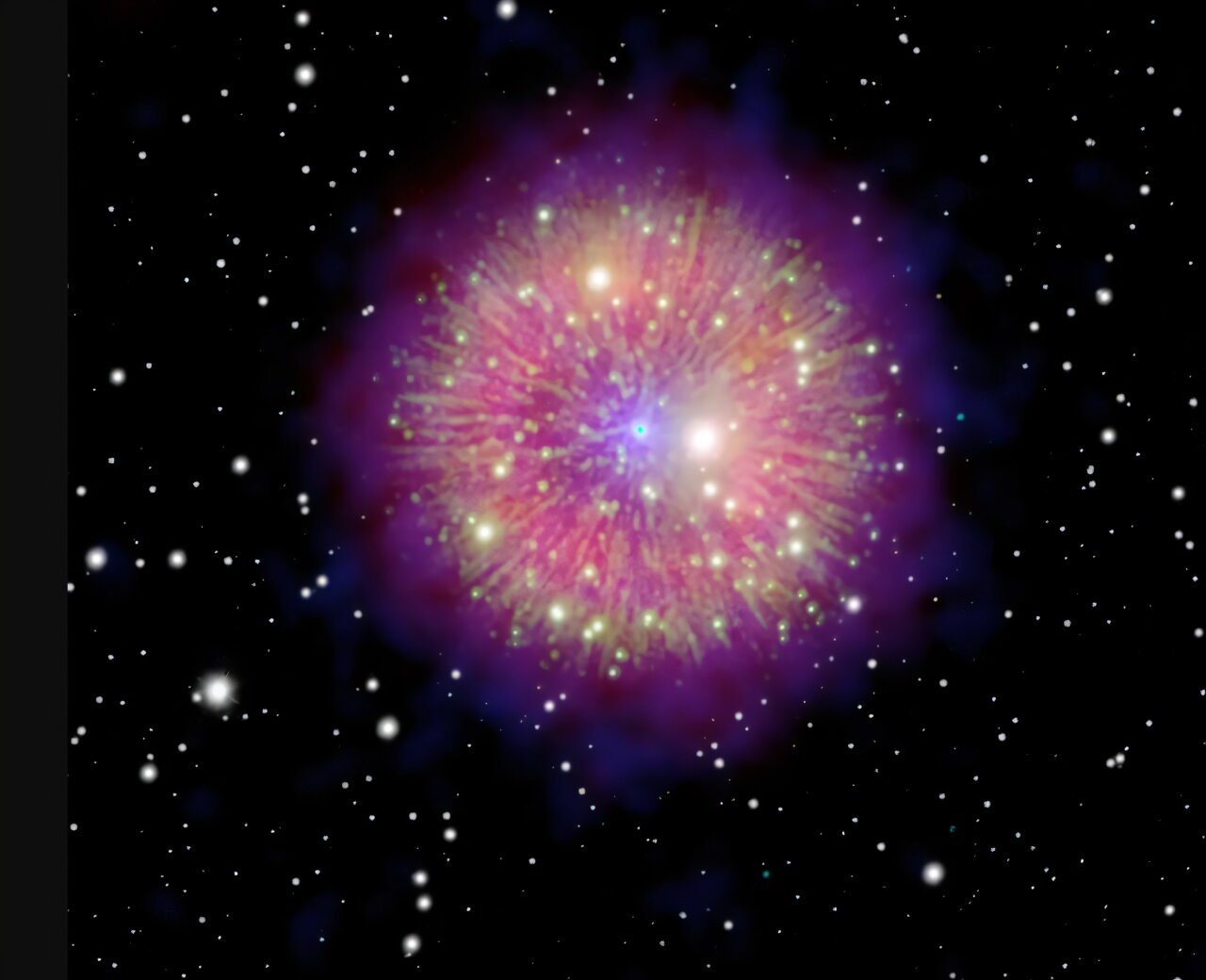

SN 1181 is especially intriguing to astrophysicists because it may represent a rare Type Iax explosion—one that doesn’t entirely destroy the star but leaves behind a dim, “zombie” remnant. If confirmed, it would be the first of its kind identified in our own galaxy.

A Sky Without Supernovae

It may seem strange that we haven’t witnessed such an event in modern times. The last supernova visible to the naked eye in our galaxy was “Kepler’s Star” in 1604—over four centuries ago. Since then, the Milky Way has remained quiet, at least from our vantage point.

Yet astronomers know that stars continue to die and be born within our galaxy’s spiral arms. The odds simply haven’t favored another bright explosion in our skies. The next one might already have occurred, hidden behind clouds of interstellar dust—or perhaps it’s about to, in a star we can already see.

The red supergiant Betelgeuse, for example, sits some 500 light-years away in Orion and has shown unusual dimming behavior in recent years. One day, it too will end in a titanic supernova, briefly shining as bright as a full moon. Whether that happens tomorrow or a hundred thousand years from now, no one can say.

The Power of Old Words and New Eyes

The rediscovery of these Arabic records does more than fill gaps in our astronomical timeline—it reveals the continuity of human curiosity. Across centuries and cultures, people have looked at the same sky, wondered at its mysteries, and tried to capture them in words.

Each historical account, whether written by a Chinese monk, an Arab poet, or a European scholar, is a piece of a cosmic puzzle. When assembled, they tell not just the story of stars, but of humanity’s relentless desire to understand them.

For researchers like Neuhäuser, the work continues. “I am currently reconstructing the light curves and color evolution of the supernovae of 1572 and 1604,” he says, referring to the ones observed by Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler. “Many new records are still being found.”

Waiting for the Next Cosmic Light

Supernovae are more than astronomical curiosities—they are cosmic reminders of creation and impermanence. When one appears, it transforms the sky for weeks or months, a brilliant wound of light in the blackness of space. Then, as quickly as it came, it fades, leaving behind a nebula, a pulsar, or sometimes, a ghostly ember.

We may never again see the exact brilliance that dazzled observers in 1006 or 1181, but one day, perhaps soon, another will appear—a beacon visible to every eye on Earth. When that happens, we’ll join hands across time with the ancient astronomers who first looked up and marveled at a “new star.”

Their words remind us that science and wonder are not opposites, but partners. In every observation lies a story; in every story, a spark of discovery. The sky that inspired Ibn Sanāʾ al-Mulk and al-Maqrīzī still stretches above us tonight—waiting for the next explosion, the next poem, the next chapter in humanity’s dialogue with the stars.

And when that moment comes, we too will look up and smile—just as the heavens once did, when they adorned themselves with a new and shining star.

More information: J. G. Fischer et al, New Arabic records from Cairo on supernovae 1181 and 1006, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2509.04127