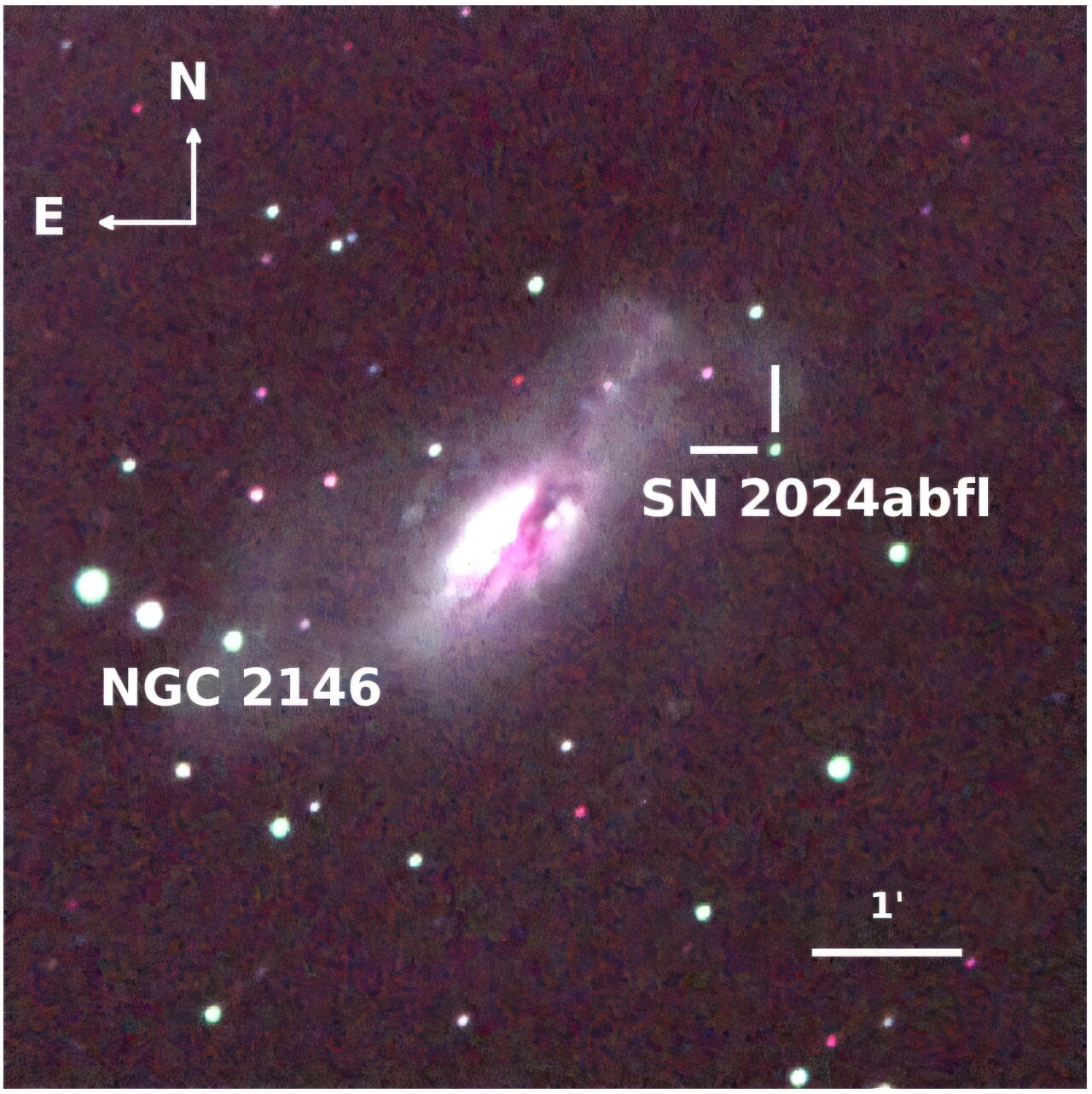

On November 15, 2024, a faint but unmistakable spark appeared in the galaxy NGC 2146. At an apparent magnitude of 17.5, it was not the brightest beacon in the sky, but to astronomers, it was a thrilling discovery. The object would soon be named SN 2024abfl, and it marked the violent end of a star’s life.

An international team of astronomers quickly turned their attention toward it. Through careful photometric and spectroscopic observations, they began tracing the light and dissecting the spectrum of this stellar explosion. Their findings, released on February 4 on the preprint server arXiv, would reveal that this was no ordinary cosmic detonation.

To understand why this event matters, we must first step back and look at what supernovae really are.

The Language of Exploding Stars

A supernova is one of the universe’s most dramatic finales. It is a powerful, luminous stellar explosion that marks the death of a star. These explosions are more than celestial fireworks. They are clues, scattered across space, helping astronomers decode how stars live, evolve, and ultimately transform galaxies.

Supernovae are sorted into two broad families based on their atomic spectra. Type I supernovae show no hydrogen in their spectra. Type II supernovae, by contrast, display clear hydrogen spectral lines. That simple presence or absence of hydrogen tells scientists something fundamental about the star that exploded.

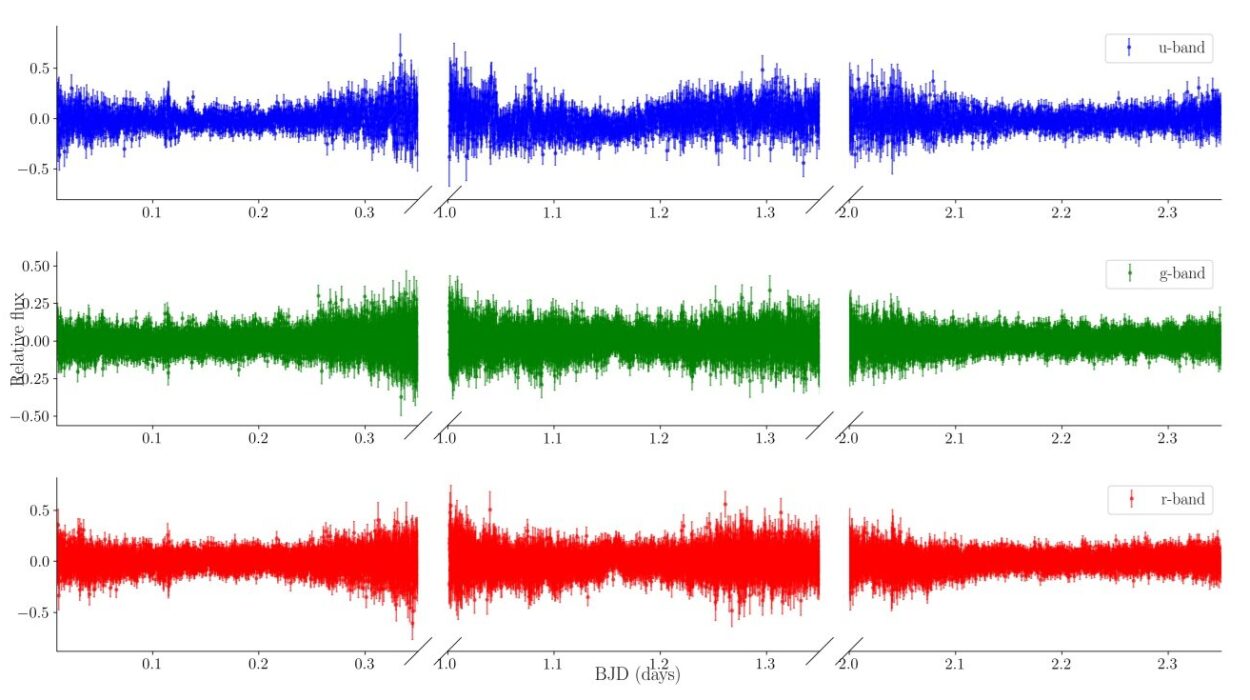

Even within Type II supernovae, there is another distinction. Astronomers study their light curves, which trace how brightness changes over time. Some Type II events fade quickly in a fairly straight line after reaching peak brightness. These are known as Type II-Linear (SNe IIL). Others hold their brightness steady for a surprisingly long time before dimming. These are called Type II-Plateau (SNe IIP).

A typical plateau for a standard SN IIP lasts about 100 days. During this time, the supernova shines with a steady brilliance, as though pausing before its final fade into darkness.

SN 2024abfl belonged to this plateau group. But it had its own story to tell.

A Plateau That Refused to Hurry

After its discovery, astronomers focused their telescopes—especially those at the Xinglong Station observatory in China—on SN 2024abfl. Led by Xiaohan Chen of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the team monitored its changing light and evolving spectrum with precision and patience.

What they found was striking. The plateau phase of SN 2024abfl lasted about 126.5 days. That is significantly longer than the roughly 100-day plateau typical of standard Type IIP supernovae. A longer plateau hints at something physical and substantial: a thick hydrogen envelope surrounding the star before it exploded. Hydrogen, glowing and recombining over time, can keep a supernova shining steadily for months.

But the brightness itself told a different story. The absolute magnitude during the plateau was about −15 mag, noticeably dimmer than normal Type IIP supernovae. This placed SN 2024abfl firmly in the category of a low-luminosity SN IIP.

So here was a paradox of sorts. A long-lasting plateau, yet a faint glow. A thick hydrogen envelope, yet a relatively subdued explosion. Something about this star’s life and death set it apart.

The Slow Breath of Ejecta

The team did not stop at brightness alone. They examined the spectral evolution of the supernova, tracking how its light shifted and changed over time.

In many ways, SN 2024abfl behaved like other Type IIP supernovae. Its spectral development followed familiar patterns. But one difference stood out clearly: the ejecta velocities were much lower than those seen in similar supernovae at comparable stages.

Ejecta are the stellar layers blasted outward by the explosion. Their speed reflects the violence of the blast. Lower velocities suggest a less energetic push. It was as if this star exhaled rather than roared.

About 37 days after the explosion, astronomers observed a high-velocity hydrogen-alpha absorption feature. This likely signaled a plume of material deep within the ejecta moving faster than its surroundings. Even in a generally slower explosion, there were pockets of urgency—hidden currents racing outward.

Then, 24 days later, two emission features appeared at velocities of around 2,000 km/s. These features were likely caused by interaction between the expanding debris and the surrounding circumstellar medium. In other words, the exploding star’s remnants were colliding with material it had shed earlier in its life. The star was interacting with its own past.

By about 138 days after the explosion, SN 2024abfl entered the nebular phase, a stage when the supernova becomes more transparent and deeper layers of material reveal themselves through emission lines. At this point, the explosion transitions from a bright, glowing sphere to a more ghostly remnant, lit from within by radioactive decay.

Counting the Ashes of a Star

Behind the glow of every supernova lies a physical accounting. How much material was thrown into space? How much energy was released? What elements were forged?

The team estimated that SN 2024abfl produced about 0.009 solar masses of nickel-56. This radioactive isotope plays a critical role in powering the late-time light of supernovae. Compared to many brighter events, this is a relatively small amount, consistent with the supernova’s low luminosity.

The explosion carried an initial kinetic energy of about 42 quindecillion ergs. While that number is staggering in everyday terms, it fits with the picture of a lower-energy event compared to more luminous Type IIP supernovae.

The total ejecta mass was estimated at 8.3 solar masses. That means a significant amount of stellar material was hurled into space, even in this relatively modest explosion.

Perhaps most evocative of all was the estimated radius of the progenitor star: nearly 1,000 solar radii. That immense size points unmistakably toward a supergiant star. Before it exploded, this star must have been swollen and vast, dwarfing our Sun in size though not necessarily in mass.

Archival data from the Hubble Space Telescope revealed a possible progenitor with an initial mass between 9 and 12 solar masses. The new study suggests that the progenitor’s mass was lower than 15 solar masses, reinforcing the idea that this was a relatively low-mass red supergiant.

The Quiet Fall of a Red Supergiant

Taken together, the evidence paints a coherent picture. SN 2024abfl was a low-luminosity SN IIP that originated from a low-mass red supergiant progenitor.

It was not a record-breaking explosion. It did not blaze with extreme brightness or hurl its outer layers at extraordinary speeds. Instead, it unfolded in a slower, dimmer, but deeply revealing way.

A thick hydrogen envelope sustained its long plateau. Lower ejecta velocities and modest nickel production kept its glow subdued. Its mass and radius tell of a star that lived a relatively quiet life compared to the most massive giants, only to end in a restrained but still powerful burst.

And yet, even in its quietness, SN 2024abfl has become a storyteller.

Why This Stellar Death Matters

Supernovae are more than cosmic spectacles. They are laboratories. Each one offers a different set of conditions, helping astronomers refine their understanding of how stars live and die.

SN 2024abfl adds a valuable piece to the puzzle of low-luminosity Type IIP supernovae. Its long 126.5-day plateau, its relatively faint −15 mag brightness, its low ejecta velocities, and its modest nickel-56 mass all contribute to a clearer picture of how lower-mass red supergiants end their lives.

By connecting its observed properties to a progenitor mass below 15 solar masses, the study strengthens the link between certain red supergiants and low-luminosity explosions. It also highlights the diversity within Type IIP supernovae. Not all plateau supernovae are equally bright or equally energetic. Some are quieter, slower, and more restrained.

Understanding these differences is essential. Supernovae shape galaxies, enrich space with heavy elements, and mark the final chapters of stellar evolution. By carefully measuring one such explosion—light curve by light curve, spectrum by spectrum—astronomers are refining the story of how ordinary stars end in extraordinary ways.

In the fading glow of SN 2024abfl, we glimpse not just the death of a distant star, but the subtle variety of cosmic endings. Even a dim supernova, shining softly across millions of light-years, can illuminate profound truths about the universe.

Study Details

Xiaohan Chen et al, SN 2024abfl: A Low-Luminosity Type IIP Supernova in NGC 2146 from a Low-Mass Red Supergiant Progenitor, arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2602.04309