On July 2, 2025, during what was meant to be an ordinary sweep of the sky, something refused to stay ordinary.

The Einstein Probe (EP), a China-led space telescope built to hunt the universe’s most fleeting outbursts, caught sight of an exceptionally bright X-ray source. At first glance, it looked like just another transient flash in the vast darkness. But within moments, astronomers realized this was no routine signal. Its brightness was changing violently and rapidly, rising and falling in ways that defied the usual cosmic script.

The signal was so unusual that it immediately triggered follow-up observations from telescopes around the world. The cosmic detective story had begun.

Scientists would later give the event a name that sounded almost clinical—EP250702a, also known as GRB 250702B. But behind that label was a mystery that could rewrite what we know about how black holes feed.

The Telescope with a Wide Eye on the Sky

This discovery did not happen by chance alone. It was made possible by the Einstein Probe’s two complementary X-ray instruments, each designed to catch different aspects of high-energy phenomena.

The first to notice the anomaly was the Wide-field X-ray Telescope (WXT). Equipped with advanced lobster-eye micro-pore optics, it scans huge swaths of the sky with remarkable sensitivity. During its routine survey, WXT detected a transient X-ray source that wasn’t just bright—it was unstable, flickering with intense variability.

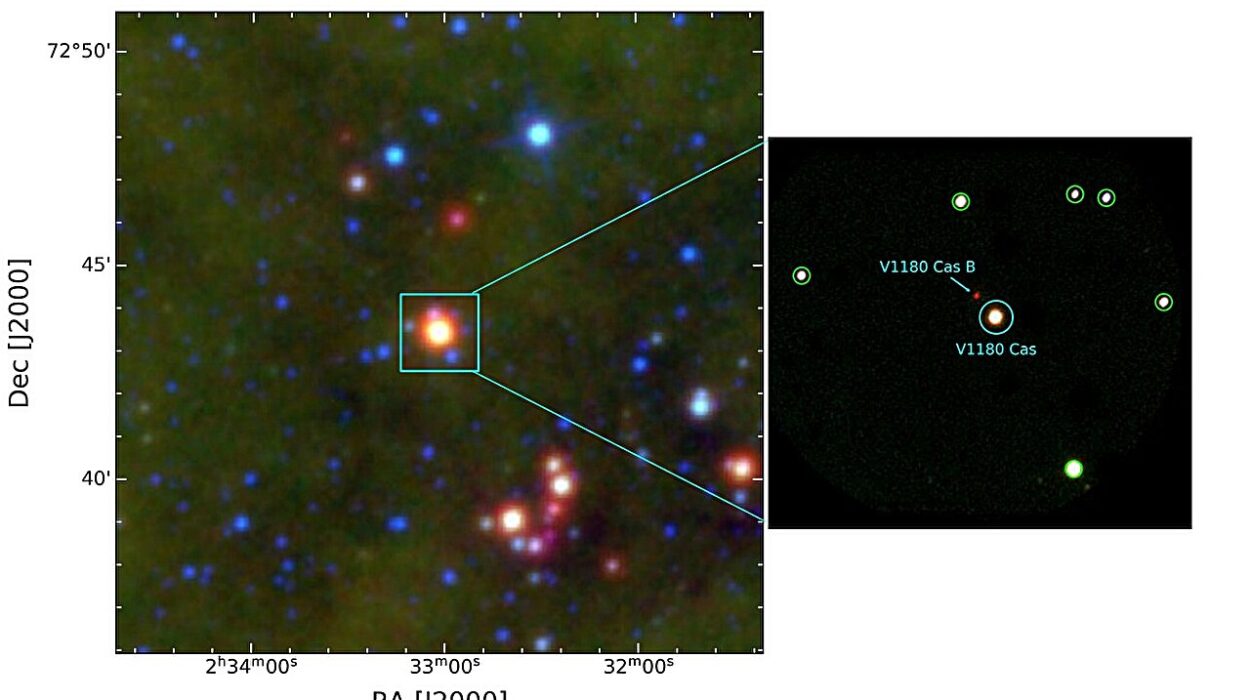

Almost simultaneously, NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected a series of gamma-ray bursts from the same region of space. That coincidence alone was intriguing. But the real twist came when scientists looked backward in time.

When researchers examined WXT’s earlier data, they found that the telescope had already detected persistent X-ray emission from that exact location about a day before the gamma-ray bursts appeared.

That sequence—X-rays first, gamma rays later—rarely happens in known high-energy cosmic explosions.

As Dr. Dongyue Li from the National Astronomical Observatories of China put it, “This early X-ray signal is crucial. It tells us this was not an ordinary gamma-ray burst.”

The Eruption That Reached the Extreme

About fifteen hours after the first unusual signal, the source erupted.

A series of intense X-ray flares burst outward, pushing the event to a peak luminosity of approximately 3 × 10⁴⁹ erg s⁻¹. In that brief instant, EP250702a became one of the brightest instantaneous outbursts ever observed in the universe.

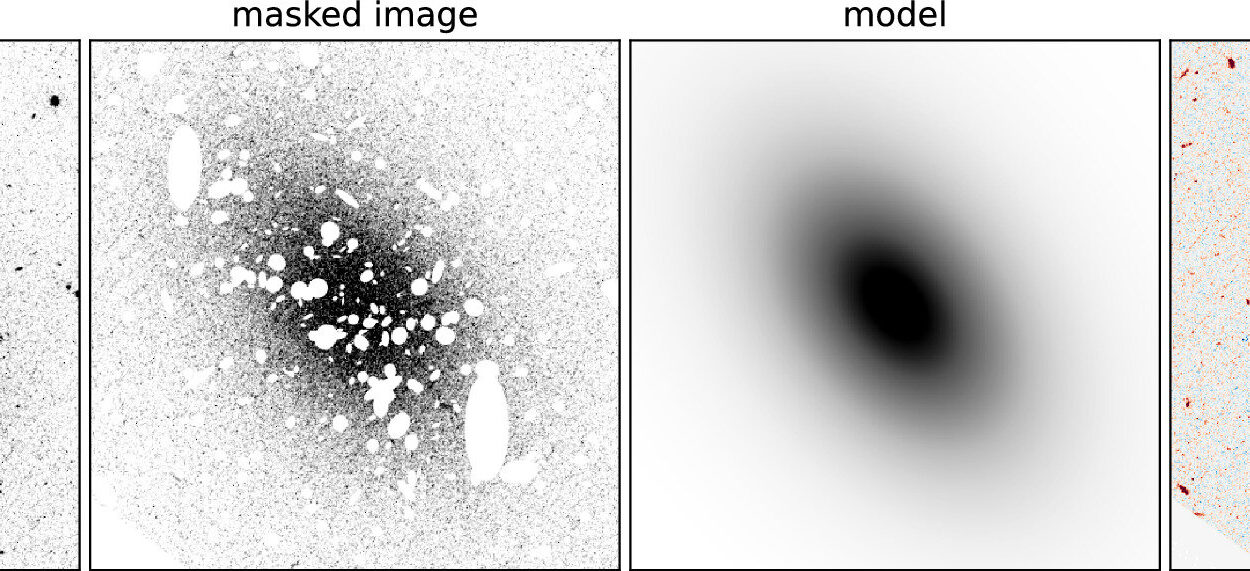

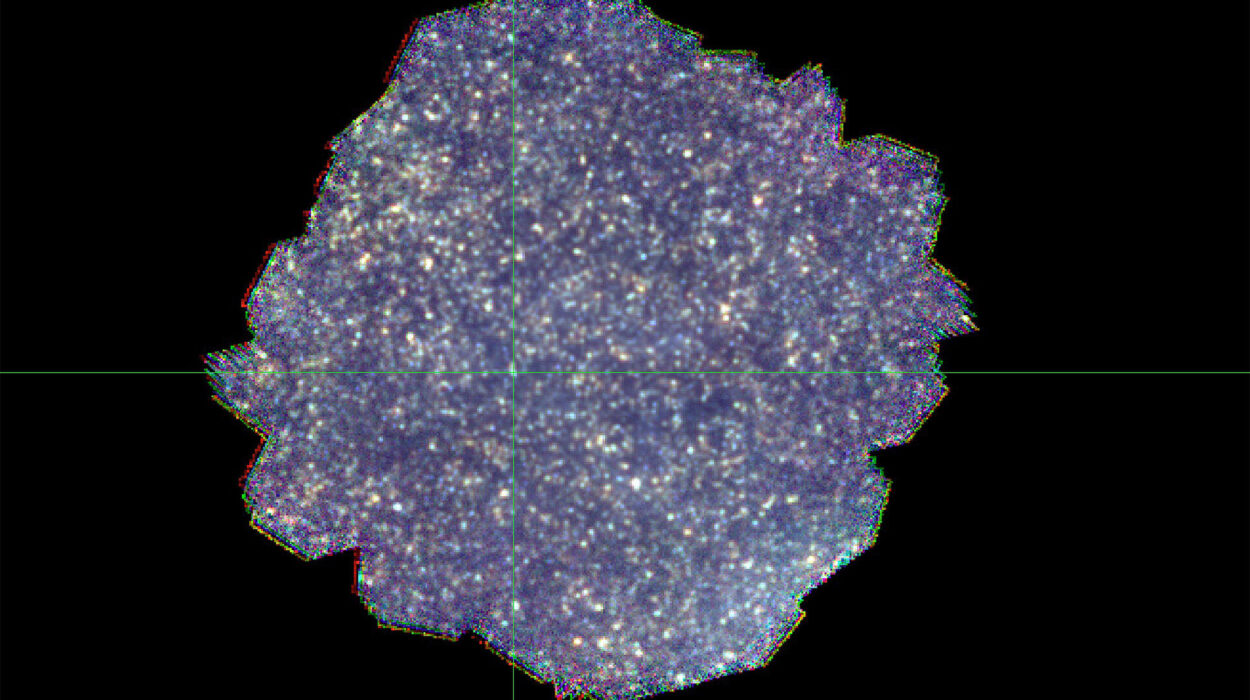

The Einstein Probe’s precise coordinates allowed large telescopes worldwide to quickly lock onto the object. Observations across multiple wavelengths confirmed its location—not at the center of its host galaxy, but in the outskirts of a distant galaxy. That detail would become critical.

Then EP’s second instrument, the Follow-up X-ray Telescope (FXT), took over. Over roughly 20 days, it tracked the source as its brightness plummeted by more than a hundred thousand times. Meanwhile, its X-ray emission shifted from higher-energy “hard” states to lower-energy “soft” states.

The event was evolving at a breathtaking pace.

And yet, even with data pouring in from across the electromagnetic spectrum, the event refused to fit neatly into existing models.

A Pattern That Broke the Rules

Scientists began lining up possible explanations. Was this some unusual gamma-ray burst? A rare stellar collapse? Something else entirely?

But the pieces did not align.

The X-rays had appeared before the gamma rays. The brightness had been extraordinarily high. The evolution had been remarkably fast. And the event’s location—far from the galaxy’s center—did not match the usual pattern of many known high-energy cosmic events.

Existing models struggled to account for all these features at once.

Then a bold idea began to stand out from the crowd.

What if this was the moment when an intermediate-mass black hole tore apart and consumed a white dwarf star?

It was a dramatic hypothesis. And if true, it would represent something never directly observed before.

When a Black Hole Meets a White Dwarf

The collaboration behind the Einstein Probe data spanned institutions in China and abroad. At the University of Hong Kong (HKU), astrophysicists played a key role in interpreting what they were seeing.

Professor Lixin Dai, from HKU’s Department of Physics and the Hong Kong Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics (HKIAA), provided the crucial theoretical judgment that shifted attention toward the white dwarf–intermediate-mass black hole model.

“The white dwarf–intermediate-mass black hole model can most naturally explain its rapid evolution and extreme energy output,” she explained.

To test this idea, Dr. Jinhong Chen, a postdoctoral fellow at HKU and co-first author of the study, ran in-depth numerical simulations. The question was simple but profound: could the tidal forces of an intermediate-mass black hole, acting on the extreme density of a white dwarf, produce the kind of explosive energy and rapid timescales seen in EP250702a?

The simulations suggested yes.

According to Dr. Chen, the combination of intense tidal forces and the compact nature of the white dwarf could generate jet energies and evolutionary patterns highly consistent with the observational data. In this scenario, as the white dwarf is torn apart, material spirals inward, and a powerful relativistic jet is launched—producing the brilliant X-ray and gamma-ray signals observed.

The model fit not just one or two features, but the entire strange sequence: early X-rays, extreme luminosity, rapid fading, and the event’s unusual location.

A Global Scientific Conversation

The findings were published as a cover article in Science Bulletin, reflecting the event’s scientific significance.

Professor Bing Zhang, Director of HKIAA at HKU, emphasized that Hong Kong’s researchers brought both international vision and technical expertise to the collaboration. Their deep involvement, he noted, highlights the city’s critical role in global astronomical exploration.

But what truly underscored the event’s importance was the vigorous debate it inspired.

As Professor Dai observed, multiple international teams proposed competing models to explain the phenomenon. That robust scientific discussion is not a sign of confusion—it is a sign of value. When nature presents something unprecedented, the global scientific community responds with creativity, skepticism, and collaboration.

At the center of it all was the Einstein Probe itself.

“The mission of the Einstein Probe is to capture unpredictable and extreme transient phenomena in the universe,” said Professor Weimin Yuan, Principal Scientist of the mission at the National Astronomical Observatories of China. The discovery of EP250702a, he said, demonstrates the mission’s ability to capture the universe’s most extreme moments—and to do so first.

Why This Discovery Could Change the Black Hole Story

If the interpretation is ultimately confirmed, EP250702a would provide the first clear, direct evidence of an intermediate-mass black hole tearing apart a white dwarf and producing a relativistic jet.

That would be more than a single dramatic event. It would fill a longstanding gap.

Intermediate-mass black holes are thought to exist between smaller stellar-mass black holes and the supermassive giants found at galactic centers. Yet direct evidence for their behavior has remained elusive. Capturing one in the act of shredding a compact star would help illuminate this missing population.

Such a discovery would also open new paths for understanding how black holes grow, what ultimately happens to compact stars like white dwarfs, and how extreme cosmic events send signals across multiple forms of radiation.

EP250702a began as a flicker in a routine sky survey. But it may turn out to be a watershed moment—a glimpse of a rare cosmic encounter that reshapes our understanding of black holes and their hidden lives.

In the end, this story is about more than a flash of X-rays. It is about the power of watching the sky continuously and carefully, about the value of global collaboration, and about how the universe still holds events so extreme that they force science to stretch its imagination.

Somewhere in the outskirts of a distant galaxy, a compact star may have met its end in the grip of a hungry black hole. And because a telescope was watching at just the right moment, we may now be closer to understanding one of the universe’s most mysterious inhabitants.

Study Details

Dongyue Li et al, A fast powerful X-ray transient from possible tidal disruption of a white dwarf, Science Bulletin (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.scib.2025.12.050