Every autumn, the heavens put on a dazzling performance as the Taurid meteor shower graces the night sky. From late October through early November, streaks of glowing light race across the darkness, leaving trails that inspire wonder and curiosity. Known as the “Halloween fireballs,” these meteors are among the brightest and slowest-moving of the year, their golden arcs often lasting long enough for even casual observers to make a wish.

In New Mexico, where wide desert skies stretch endlessly and city lights are few, the Taurids become more than a celestial show—they are a reminder of our planet’s constant journey through the cosmic dust left behind by ancient comets. But beyond their beauty, scientists see in the Taurids a more complex and potentially concerning story—one that touches on Earth’s ongoing efforts to defend itself from space hazards.

The Origin of the Taurids: Fragments of a Dying Comet

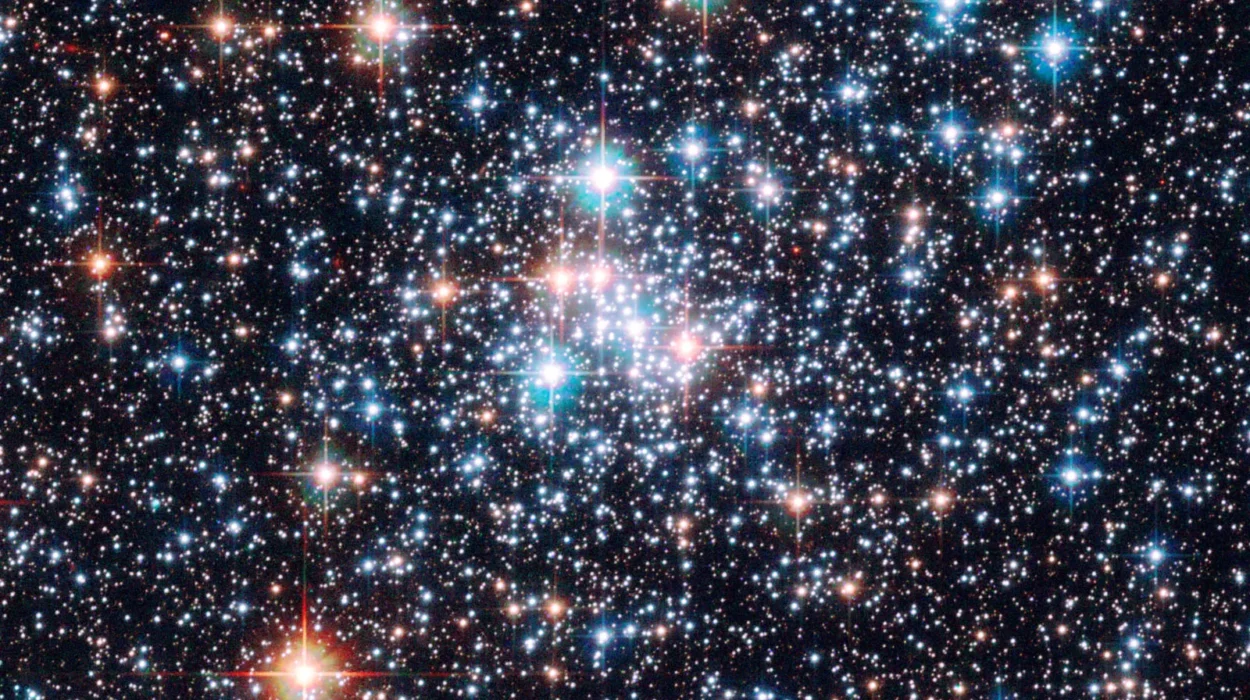

The Taurid meteor shower takes its name from the constellation Taurus, the celestial bull, where the meteors seem to radiate from. These shooting stars are not stars at all, of course—they are bits of cosmic debris burning up in Earth’s atmosphere. Each flash is caused by a tiny fragment, usually no larger than a pebble, entering the atmosphere at tens of kilometers per second.

The source of this debris is Comet Encke, one of the shortest-period comets in the solar system. Completing a lap around the sun every 3.3 years, Encke leaves behind a long, diffuse stream of dust and small rocks. As Earth passes through this stream twice each year, we encounter the Taurids—first as the daylight Beta Taurids in June, and then as the nighttime Northern and Southern Taurids in October and November.

The daytime Beta Taurids are invisible to the human eye, hidden by the glare of the sun, but the October–November Taurids deliver a more theatrical show. When these fragments enter our atmosphere, they produce brilliant fireballs—some so bright they can cast shadows and be seen even through thin clouds.

Yet the Taurids’ charm comes with a caveat. These bright meteors may be small reminders of something larger and more dangerous lurking in the same debris stream.

When Fireballs Become Hazards

While most Taurid meteors burn up harmlessly high above the ground, some researchers believe that larger objects may be traveling within the same orbital path. A new study led by Dr. Mark Boslough, a research professor and planetary impact expert, examines this possibility. Published in Acta Astronautica as part of the 2025 Planetary Defense Conference proceedings, Boslough’s research investigates whether a concentration of larger near-Earth objects (NEOs) could exist within the Taurid stream—and whether these could pose an increased impact risk to our planet in the near future.

The study, titled “2032 and 2036 Risk Enhancement from NEOs in the Taurid Stream: Is There a Significant Coherent Component to Impact Risk?”, explores the potential for what scientists call a “Taurid Resonant Swarm.” This hypothetical swarm refers to a cluster of larger objects—perhaps tens to hundreds of meters across—that orbit in resonance with Jupiter. That resonance, where the objects orbit the sun seven times for every two Jupiter orbits, allows Jupiter’s immense gravity to nudge and concentrate debris in certain regions of space.

Boslough compares this to a prospector swirling a pan in search of gold—each motion of Jupiter’s gravity gathering particles into denser clumps. If Earth happens to pass through one of those clumps, the number of incoming objects—and the associated risk—could temporarily rise.

Planetary Defense: Protecting Earth from the Skies

“Planetary defense is the multidisciplinary and internationally coordinated effort to protect Earth and its inhabitants from impacts by near-Earth objects,” Boslough explains. This field combines astronomy, physics, engineering, and emergency management. Its goals include discovering and tracking asteroids, modeling their potential effects, and developing ways to prevent or mitigate impacts.

A near-Earth object is defined as any asteroid or comet whose orbit brings it close to Earth’s. These objects can range from small pebbles to kilometer-wide asteroids capable of causing global damage. Fortunately, most are small, and large impacts are extremely rare. Still, events like the 2013 Chelyabinsk airburst over Russia remind scientists that even modest-sized objects can cause real harm.

The Chelyabinsk meteor, about 60 feet wide, exploded in the atmosphere with the energy of half a megaton of TNT—roughly 30 times the power of the Hiroshima bomb. It injured over 1,500 people, mostly from shattered glass after a blinding flash prompted many to rush to windows. A century earlier, in 1908, a far more powerful explosion flattened 800 square miles of Siberian forest in the Tunguska event, likely caused by a rock about 200 feet wide.

These are reminders that small asteroids striking Earth’s atmosphere can unleash enormous energy. Boslough’s models suggest that if a Taurid swarm contains even a few such objects, Earth could face a temporarily elevated risk during years when the swarm passes near our orbit—specifically in 2032 and again in 2036.

The Hypothesis of the Taurid Resonant Swarm

The Taurid Resonant Swarm, or TRS, remains a theoretical concept, but observations provide intriguing hints. Astronomers have recorded unusual concentrations of bright fireballs during certain years, consistent with the predicted timing of the swarm. Even seismic sensors on the Moon have detected impact signatures at those times, possibly from Taurid fragments striking its surface.

Boslough’s team incorporated these observations into their models and found that the risk from “airburst-sized” NEOs—objects that would explode in the atmosphere rather than hit the ground—could be larger than current estimates suggest.

“The resonant swarm is theoretical,” Boslough notes, “but there is some evidence that a sparse swarm of small objects exists because bright fireballs and seismic signatures of impacts on the moon have been observed at times that the theory has predicted.”

If this swarm does exist, Earth could pass through a denser section of it in 2032 and 2036, potentially bringing a higher-than-usual number of larger meteoroids into our skies. The good news: even then, the overall probability of a serious impact remains low.

Observing the Skies and Preparing for the Future

The upcoming close approaches of 2032 and 2036 offer a unique opportunity for astronomers to put the Taurid swarm hypothesis to the test. According to Boslough, existing telescopes can conduct targeted surveys to look for these objects when Earth nears the predicted intersections.

“If we discover the objects with enough warning time, then we can take measures to reduce or eliminate the risk,” Boslough says. “If the new infrared telescope—NEO Surveyor—is in operation, then we can potentially have much more warning time.”

The NEO Surveyor mission, led by NASA and scheduled for launch later this decade, is designed specifically to find and track hazardous asteroids using infrared light, which can detect dark objects that reflect little visible light.

In New Mexico, facilities such as the Magdalena Ridge Observatory near Socorro are already contributing to planetary defense observations. Scientists at Sandia National Laboratories (SNL) and Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) also play leading roles in modeling asteroid impacts and testing mitigation strategies.

Lessons from the Past

Understanding how to respond to a potential impact event is as important as predicting one. The Chelyabinsk event taught experts that most injuries resulted not from the explosion itself, but from people reacting to the sudden light. “If a similar event were to occur over New Mexico,” Boslough notes, “this would likely be the primary cause of injury.”

The key lesson: if you see a bright flash in the sky, stay away from windows. Do not look directly at it. Wait for the shockwave to pass. Public awareness can make the difference between panic and safety.

Boslough also emphasizes the need for perspective. Asteroid impacts are only one category of natural hazard, alongside earthquakes, volcanoes, hurricanes, and wildfires. While the average person’s chance of being affected by an asteroid is extremely small, understanding the risk—and supporting ongoing research—helps ensure that we remain prepared for rare but high-consequence events.

Separating Science from Myth

As with many cosmic topics, the Taurid swarm has attracted sensational claims on social media and pseudoscientific websites. Some fringe theories have suggested that past climate catastrophes or even ancient civilizations were destroyed by Taurid impacts. Boslough, who has spent years debunking misinformation, warns the public to rely on peer-reviewed science rather than speculation.

He points to a recent example in which a journal retracted a paper claiming that an ancient city in Jordan was obliterated by a Tunguska-style airburst—research later shown to be based on misinterpreted evidence. Boslough’s own analyses were instrumental in that retraction.

He also coauthored a detailed refutation of the idea that the Taurid swarm caused a mass extinction or triggered a sudden global cooling event 12,900 years ago. “A lot of false information and mythology about this subject has been promulgated on social media and sensational TV shows,” he said. “It gives the public the wrong impression about NEOs, impacts, and airbursts, and what we can do to reduce the risk.”

A Sky Worth Watching

For now, the Taurid meteor shower remains an event of beauty, not fear. In 2025, the show will peak around Halloween—an appropriate time for the “Halloween fireballs” to make their annual appearance. Boslough recommends venturing out after 2 a.m., when the radiant point in Taurus is highest and the moon has set. For the best view, find a dark location far from city lights, give your eyes time to adjust, and simply look up.

A few days after the full moon on November 5, the Taurids will again be visible in the early evening sky before moonrise. While most meteors will be faint, a few might blaze bright enough to momentarily turn night into day.

As you watch the fireballs streak across the heavens, remember that these lights are the dying sparks of ancient cosmic fragments—tiny emissaries from a comet that has circled the sun for millennia. They remind us of our planet’s place in a vast, dynamic universe, where beauty and danger coexist in equal measure.

The Balance of Wonder and Vigilance

The story of the Taurids captures both the romance of the night sky and the scientific seriousness of planetary defense. For thousands of years, humans have looked up at meteors with awe, interpreting them as omens, messages, or magic. Today, science reveals their true nature—natural events that link us directly to the processes shaping our solar system.

Still, the emotional power of these streaks of light remains unchanged. They connect us to the cosmos, reminding us that we are travelers through a universe that is both breathtakingly beautiful and unpredictably alive.

As researchers like Mark Boslough work to understand and prepare for potential cosmic hazards, the rest of us can continue to marvel at the spectacle above. The Taurid meteor shower invites us to look up—not just with curiosity, but with gratitude for the fragile, protected world we call home.

More information: Mark Boslough et al, 2032 and 2036 risk enhancement from NEOs in the Taurid stream: Is there a significant coherent component to impact risk?, Acta Astronautica (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2025.09.069