On a clear, moonless night, far away from the glow of city lights, the sky unfolds like a theater of stars. Constellations trace ancient myths across the heavens, planets glide silently in their orbits, and countless points of light shimmer above us like cosmic lanterns. To the unaided eye, these stars may appear scattered and solitary, but each one belongs to something vastly larger — galaxies, the colossal star cities that populate the observable universe.

This leads to a fascinating question that blends astronomy, curiosity, and our yearning for cosmic connection: Can we see other galaxies with the naked eye? Can a human, standing on Earth with no telescope, actually peer across intergalactic space and witness the light of another galaxy?

The answer is yes — but it’s more than a simple yes. It’s a journey into scale, perception, human limits, cosmic architecture, and the incredible majesty of the night sky. To understand which galaxies we can see, and why we can see them, we must first understand what a galaxy truly is.

What Is a Galaxy?

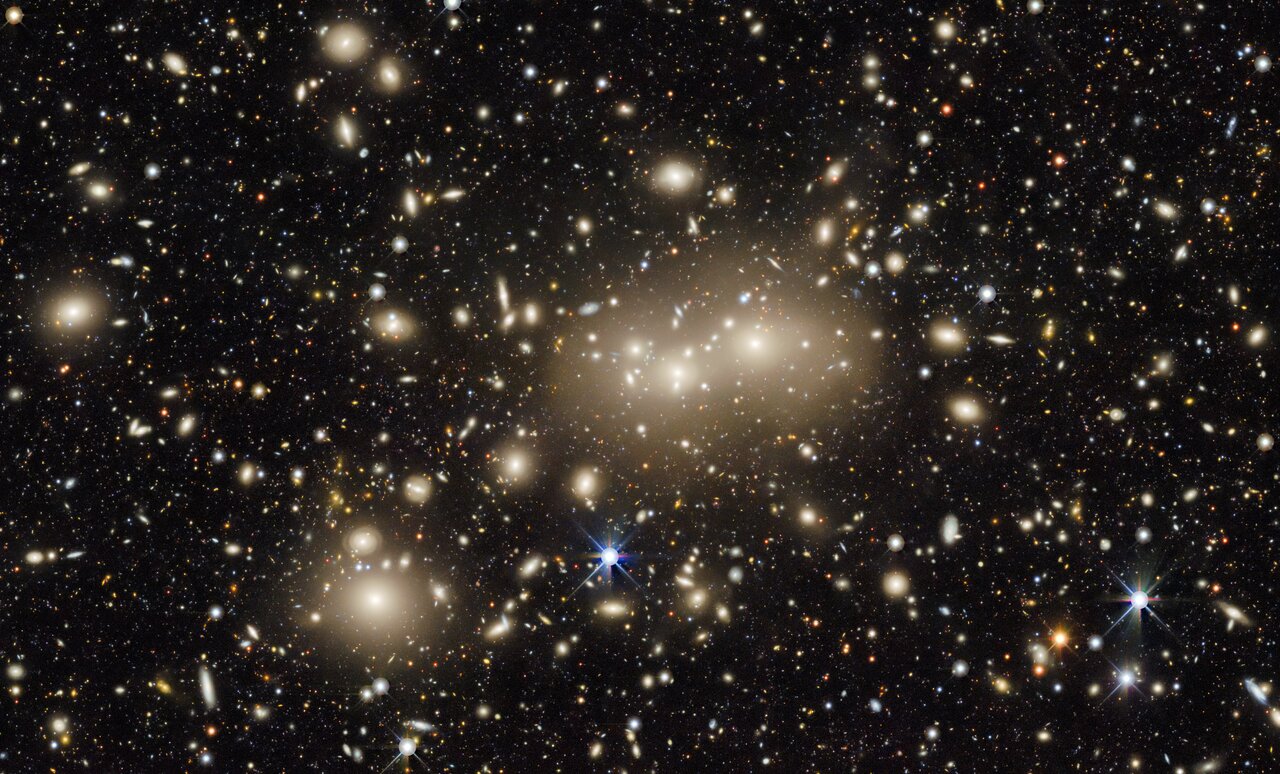

A galaxy is not a star — it’s a gravitationally bound system of millions, billions, or even trillions of stars, along with gas, dust, dark matter, and other celestial phenomena. Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is a spiral galaxy containing over 200 billion stars, along with nebulae, black holes, and star-forming regions. Its diameter is estimated to be about 100,000 light-years across.

Galaxies come in many shapes and sizes — spirals, ellipticals, irregulars — and they are the fundamental units of structure in the universe. They collide, merge, evolve, and spread across the cosmos in colossal filaments and walls, separated by even vaster voids.

When we speak of “other galaxies,” we are referring to objects not part of the Milky Way, not gravitationally bound to our galactic disk. They lie beyond our stellar neighborhood, shining with their own ancient light.

But light travels through space. And the farther a galaxy is from us, the dimmer and more dispersed that light becomes. The question of visibility becomes a game of light, distance, atmospheric clarity, and human perception.

Naked Eye Astronomy: Limits and Capabilities

The human eye is an extraordinary organ. While it cannot match the power of a telescope, it has evolved to detect a wide range of brightness and color in natural light. In perfect conditions — with no atmospheric pollution, artificial lighting, or cloud cover — the average human eye can detect celestial objects with an apparent magnitude of about +6 to +6.5.

The apparent magnitude scale is logarithmic and inverted: the lower the number, the brighter the object. For comparison:

- The full Moon is about -12.7

- Venus at its brightest is around -4.7

- The faintest stars visible to most eyes are +6.0

- The dimmest stars seen in the city may be around +3 or +4

Most galaxies are fainter than +6, which makes them invisible to the naked eye. But there are a few exceptions — galaxies so large, so close, or so bright that they punch through the veil of darkness and reveal themselves to human vision.

The Andromeda Galaxy: Our Cosmic Neighbor

The crown jewel of naked-eye galaxies is the Andromeda Galaxy, known formally as Messier 31 (M31). Located about 2.5 million light-years away, it is the nearest large spiral galaxy to the Milky Way and is on a slow-motion collision course with us that will play out over the next several billion years.

Despite its great distance, Andromeda is enormous — about 220,000 light-years across, even larger than the Milky Way. Its sheer size and relatively close proximity allow it to be seen with the naked eye under dark skies.

To the eye, Andromeda appears as a faint, fuzzy patch of light, elongated and ghostly, often described as a smudge or an oval cloud. It is located in the constellation Andromeda, which rises in the northern sky during fall and early winter in the Northern Hemisphere. Under suburban or urban skies, it can be nearly impossible to see. But from a truly dark site — such as a desert, a mountain range, or a rural field — Andromeda can be spotted without optical aid, appearing as a quiet whisper from another world.

Though the eye sees it as a pale blur, binoculars or a small telescope can begin to reveal its structure, showing the bright galactic core and hints of the spiral arms.

What you are seeing is astonishing: the combined light of one trillion stars, taking 2.5 million years to reach your eyes. Every glance is a look back in time, a moment from a prehistoric universe making contact with you in the present.

The Large and Small Magellanic Clouds: Southern Sky Treasures

While Andromeda dominates the northern sky, the Southern Hemisphere has its own naked-eye galaxies — the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) and the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC). These are irregular dwarf galaxies located about 160,000 and 200,000 light-years away, respectively.

To observers in the Southern Hemisphere, especially in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and South America, these galaxies appear as distinct cloud-like smudges in the night sky. Unlike Andromeda, they are close companions to the Milky Way and are gravitationally bound to our galaxy, possibly on long elliptical orbits.

Both the LMC and SMC are easily visible to the naked eye under dark skies. The Large Magellanic Cloud is the fourth-brightest galaxy in the sky, and its relative closeness makes it an ideal laboratory for studying stellar formation, supernova remnants, and galactic dynamics.

The LMC is home to the Tarantula Nebula, the most active star-forming region in our local group of galaxies. Though not visible without a telescope, the presence of such regions emphasizes just how active and dynamic even small galaxies can be.

To the naked eye, these clouds appear serene, but they are buzzing with activity, teeming with stellar birth, death, and cosmic evolution.

Seeing the Triangulum Galaxy (M33)

Another galaxy that occasionally sneaks into the reach of naked-eye observers is the Triangulum Galaxy, or Messier 33. Located about 2.7 million light-years away, it is the third-largest member of the Local Group, after the Milky Way and Andromeda.

M33 is a face-on spiral galaxy, and despite being relatively close in cosmic terms, it is faint, with an apparent magnitude around +5.7. It is one of the most difficult objects to spot with the unaided eye, requiring perfect viewing conditions — dark skies, no moon, and a trained eye.

When conditions are just right, M33 can be seen as a diffuse, pale glow in the small constellation Triangulum, not far from Andromeda. Because it has low surface brightness, it is often invisible even when technically bright enough. The eye struggles to distinguish it from the surrounding skyglow, making it a prize for dedicated skywatchers.

Spotting M33 is a testament to both human perception and the subtlety of cosmic light.

Galaxies Beyond Sight: Hidden Giants

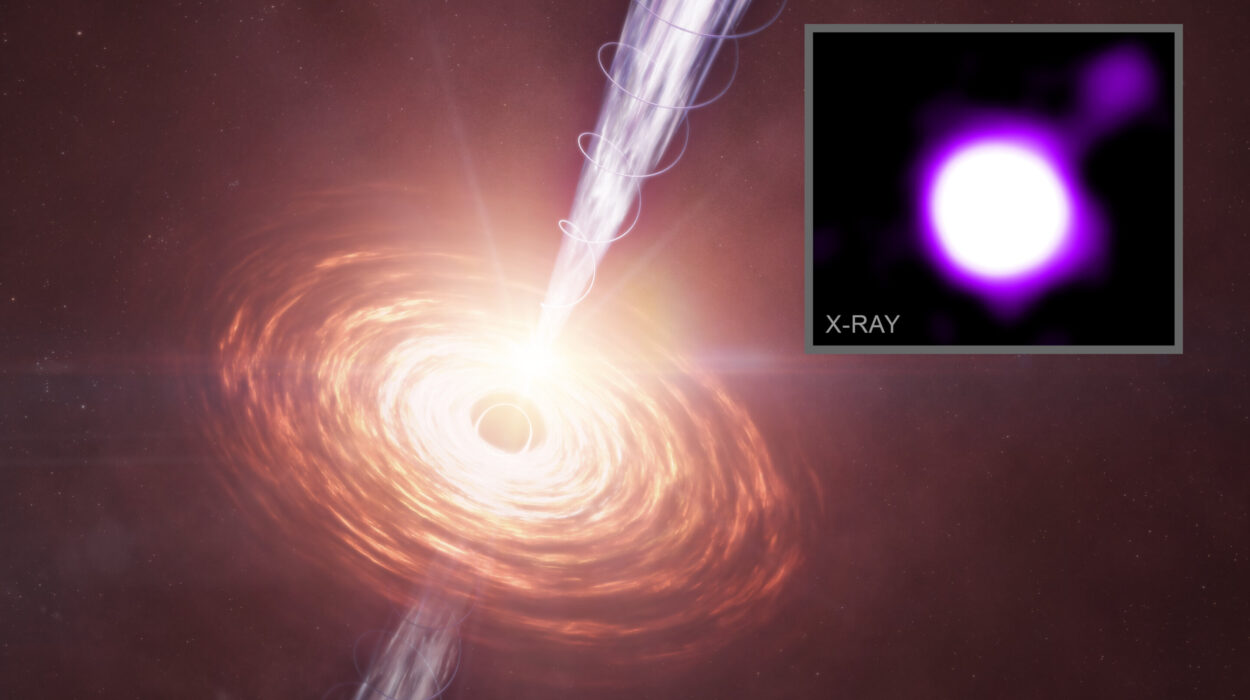

Beyond these few visible examples, the vast majority of galaxies are too far and too faint to be seen without optical aid. Most are only observable through telescopes, either amateur or professional, and many are only visible in other wavelengths — radio, infrared, ultraviolet, or X-ray.

Galaxies like Messier 81 (Bode’s Galaxy), Messier 82 (the Cigar Galaxy), NGC 253 (the Sculptor Galaxy), and NGC 4945 are tantalizingly close and bright, but not visible to the naked eye except under extremely rare and pristine conditions.

This does not diminish their importance — only our access to them. They populate the cosmic landscape like cities in the night, each with billions of stars and countless stories of stellar birth, planetary formation, and black hole activity.

Why Are Galaxies So Hard to See?

Several reasons make galaxies difficult for the human eye to perceive:

- Distance: Most galaxies are millions or billions of light-years away. Even bright galaxies like Andromeda and Triangulum are rendered faint by sheer distance.

- Surface Brightness: Galaxies are extended objects. Their light is spread over a wide area, lowering their brightness per square arcsecond, which makes them harder to detect than point-like stars.

- Atmospheric Interference: Light pollution, humidity, and even thin clouds can scatter or absorb the faint light from galaxies.

- Biological Limitations: The human eye is sensitive but not infinitely so. It can detect a candle in the dark from miles away under ideal conditions, but the diffuse light of galaxies challenges its resolution and sensitivity.

Seeing with the Soul: The Human Connection

Even when we can’t see them, galaxies are part of us. Every atom in your body was once forged in the heart of a star — perhaps in a long-dead galaxy. The light of distant galaxies still pours into Earth’s atmosphere, bathing us in invisible radiance, whispering of cosmic epochs long gone.

Astronomy connects us to a larger story — one in which humans, perched on a small planet orbiting an average star, look up and recognize their place in a vast, expanding universe.

Seeing another galaxy with your own eyes, with no telescope, is one of the most awe-inspiring experiences available to the human mind. It doesn’t just inform — it transforms. It reorients our sense of scale, our appreciation of time, and our reverence for the cosmos.

Stargazing and the Art of Stillness

Finding galaxies with the naked eye demands patience, solitude, and a willingness to slow down. In an age of artificial light, 24-hour brightness, and constant stimulation, galaxy watching is a kind of resistance — a quiet rebellion in favor of stillness and silence.

It requires you to travel away from cities, to wrap yourself in layers of clothing, and to wait for your eyes to adjust to the dark. You must learn the constellations, read star maps, and sometimes simply sit and stare until the universe unveils its secrets.

But when it happens — when Andromeda emerges from the inky void, or when the Magellanic Clouds bloom over the horizon — the feeling is one of profound humility. You are not just looking at light. You are witnessing history, seeing the ancient signal of another galaxy across the gulf of space and time.

The Future of Naked-Eye Astronomy

As light pollution increases and urban development spreads, the ability to see galaxies with the naked eye is becoming rare. Many people grow up never seeing the Milky Way, let alone another galaxy. Efforts are underway to protect dark skies through the establishment of dark sky reserves, national parks, and public education.

Technology will continue to push the boundaries of what we can detect with machines — the James Webb Space Telescope, for example, can see galaxies over 13 billion light-years away — but the magic of naked-eye viewing lies in its simplicity and intimacy.

You, standing alone beneath the sky, no tools, just eyes and stars. And yet, you see another galaxy. That moment, humble and ancient, is one of the most powerful connections between humanity and the universe.

Final Thoughts: A Universe Within Reach

So yes — we can see other galaxies with the naked eye. Not many, and not easily, but we can. The light from Andromeda, the Magellanic Clouds, and occasionally Triangulum graces our skies for those willing to seek it.

In a universe filled with wonders, the naked eye still holds its place. It is the original telescope, the primal lens through which humanity first looked up and asked the most important questions: Where are we? What is out there? Are we alone?

The galaxies answer with silence, but their light says enough. And for those who take the time to look, to really look, the cosmos reveals its greatest secret: that it is not distant or unreachable. It is already here, in our eyes, in our atoms, and in our awe.