In 2023, something extraordinary slipped quietly into Earth from the depths of space. It left no flash in the sky, no sound, no crater. Instead, it announced itself through a whisper in a detector buried far below the sea. A single neutrino, a subatomic particle so elusive it can pass through planets as if they were fog, arrived carrying an amount of energy that stunned physicists around the world.

This neutrino was not just powerful. It was impossible.

Its energy was measured at 100,000 times greater than the highest-energy particle ever produced by the Large Hadron Collider, humanity’s most powerful machine for smashing particles together. According to everything scientists knew, there were no known objects in the universe capable of creating such a particle. No exploding star, no violent galaxy, no theoretical engine could explain it.

And yet, there it was.

Now, a team of physicists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst believes this impossible visitor may be the long-awaited clue to one of the deepest mysteries in modern science. In new research published in Physical Review Letters, they argue that the neutrino may have been born from the explosive death of an exotic object called a quasi-extremal primordial black hole. If they are right, this single particle could be pointing toward the fundamental structure of the universe itself.

Black Holes Born Before Stars Existed

Most black holes have a familiar origin story. A massive star burns through its fuel, collapses inward, detonates in a supernova, and leaves behind a region of spacetime so dense that not even light can escape. These black holes are enormous, heavy, and remarkably stable. Once formed, they can persist for longer than the age of the universe.

But in 1970, physicist Stephen Hawking proposed a radically different idea. In the chaotic moments shortly after the Big Bang, the universe may have been dense and turbulent enough to create black holes directly, without the need for stars. These hypothetical objects are known as primordial black holes, or PBHs.

Unlike their stellar cousins, PBHs could be much lighter. And paradoxically, that lightness changes everything.

Hawking showed that black holes are not entirely black. Through a subtle quantum process now called Hawking radiation, black holes can slowly emit particles. For massive black holes, this radiation is negligible. But for smaller ones, it becomes increasingly important. The lighter the black hole, the hotter it becomes, and the more intensely it radiates.

Primordial black holes, if they exist, would sit at the edge of this strange behavior.

A Slow Burn That Ends in Fire

“As PBHs evaporate, they become ever lighter, and so hotter,” explains Andrea Thamm, an assistant professor of physics at UMass Amherst and co-author of the study. “They emit more and more radiation in a runaway process until explosion.”

This final stage would not be gentle. It would be violent and sudden, releasing a burst of energy in the form of subatomic particles. Crucially, this radiation could include particles we already know, particles we have only hypothesized, and possibly particles that science has never encountered before.

Such an explosion would act like a cosmic inventory, revealing a catalog of everything that exists at the most fundamental level. Electrons, quarks, Higgs bosons, hypothetical dark matter particles, and unknown entities could all pour out in a final flash.

The UMass Amherst team had previously shown that these explosions might not be exceedingly rare. They could occur as often as once every decade. And if scientists were paying attention, our existing detectors might be able to see them.

For years, this idea remained purely theoretical.

The Day Theory Met a Particle

Then came 2023.

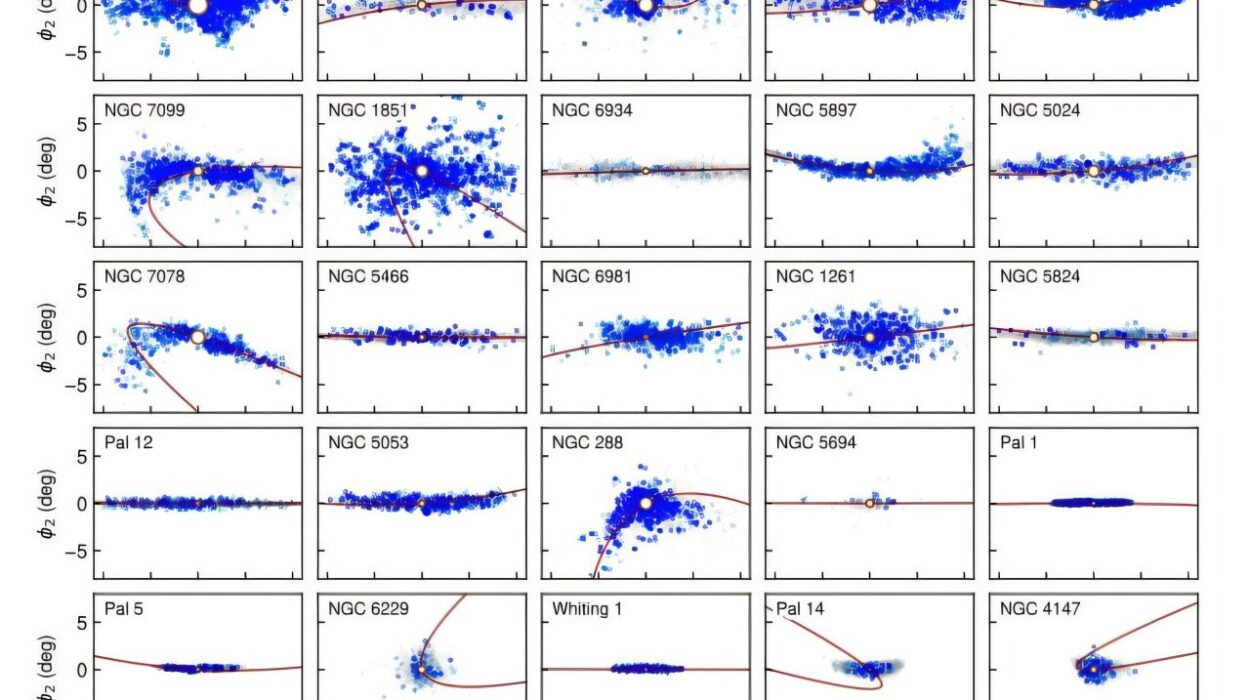

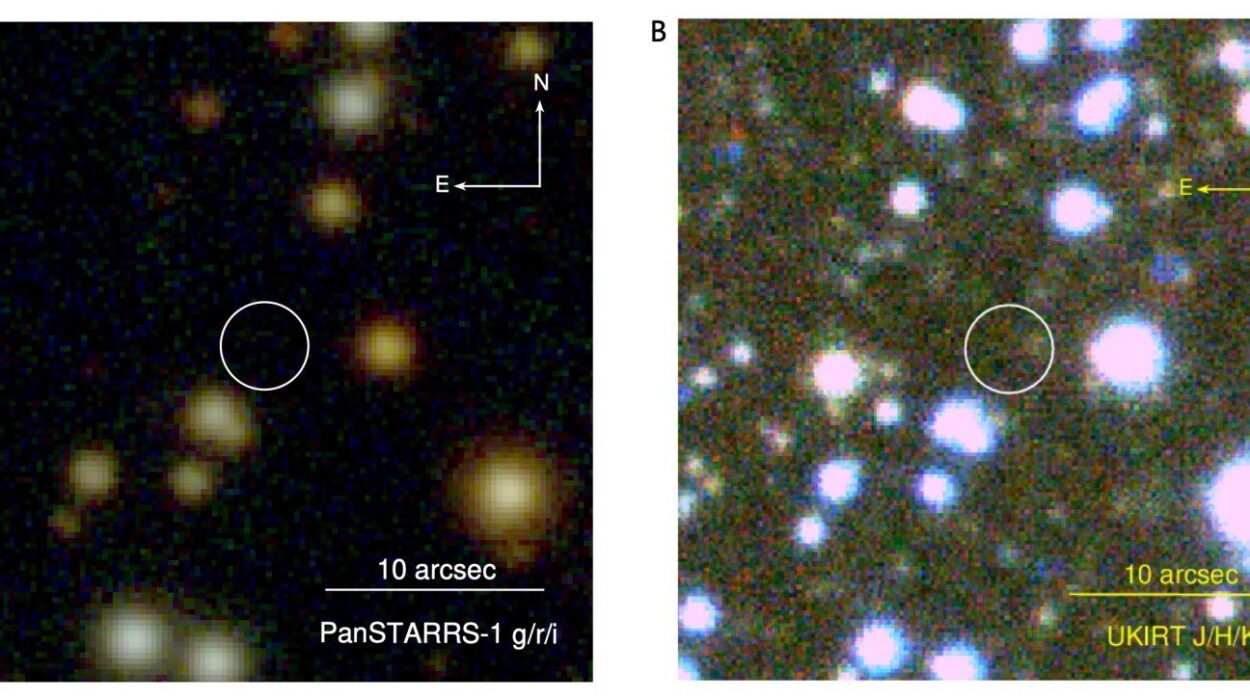

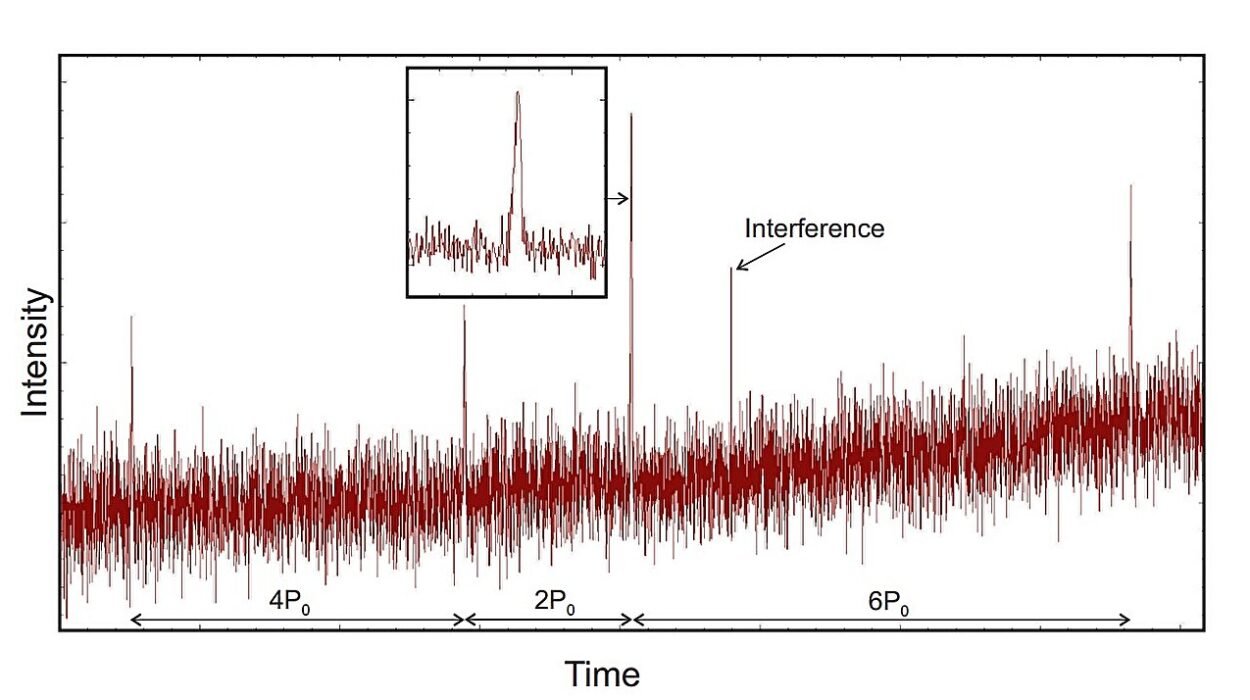

An experiment known as the KM3NeT Collaboration, designed to detect high-energy neutrinos from space, captured the signal of the impossible particle. The neutrino carried exactly the kind of extreme energy the UMass Amherst team had predicted could come from an evaporating primordial black hole.

It seemed like a triumph. But almost immediately, a problem emerged.

Another major neutrino detector, IceCube, which is also designed to capture cosmic neutrinos, saw nothing. Not only did it miss this event, it had never recorded anything with even one hundredth of the energy.

If primordial black holes were common and exploding regularly, why weren’t detectors being flooded with these high-energy neutrinos? Why did one experiment see the impossible while another saw nothing at all?

The universe, once again, refused to give up its secrets easily.

A Hidden Charge in the Darkness

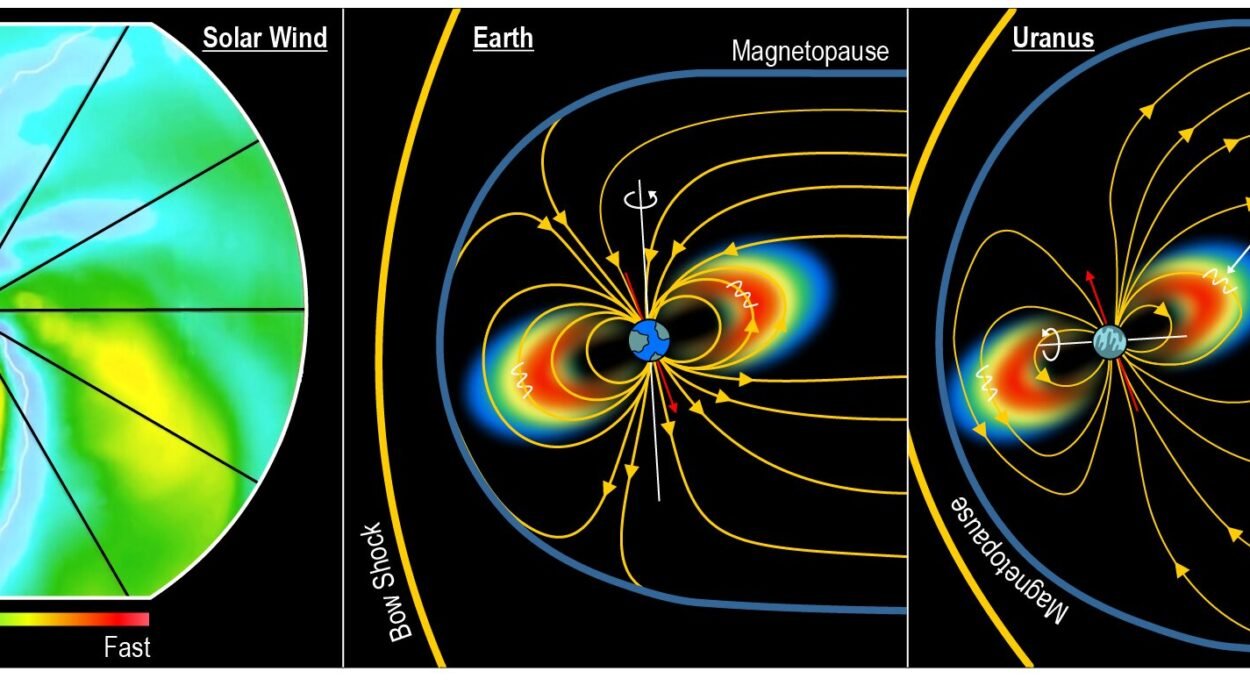

The answer, the researchers propose, lies in something entirely unfamiliar: a dark charge.

“We think that PBHs with a dark charge are the missing link,” says Joaquim Iguaz Juan, a postdoctoral researcher at UMass Amherst and co-author of the paper. These special black holes are known as quasi-extremal primordial black holes.

The dark charge is described as a hidden counterpart to the electric force. Just as ordinary electricity involves electrons and electric charge, this dark version would involve a very heavy, hypothesized particle the team calls a dark electron.

This additional charge fundamentally changes how a primordial black hole behaves as it evaporates. It alters the timing, intensity, and composition of the particles released in the final explosion.

“Our dark-charge model is more complex,” says Michael Baker, another co-author and assistant professor of physics at UMass Amherst. “But that complexity may mean it provides a more accurate model of reality.”

In this framework, only certain detectors, under specific conditions, would be likely to observe the most extreme particles produced in these explosions. That could explain why KM3NeT saw the neutrino, while IceCube did not.

According to the team, a PBH with a dark charge has unique properties that allow it to reconcile all of the seemingly inconsistent experimental data.

When One Particle Connects Everything

The implications of this idea stretch far beyond a single neutrino.

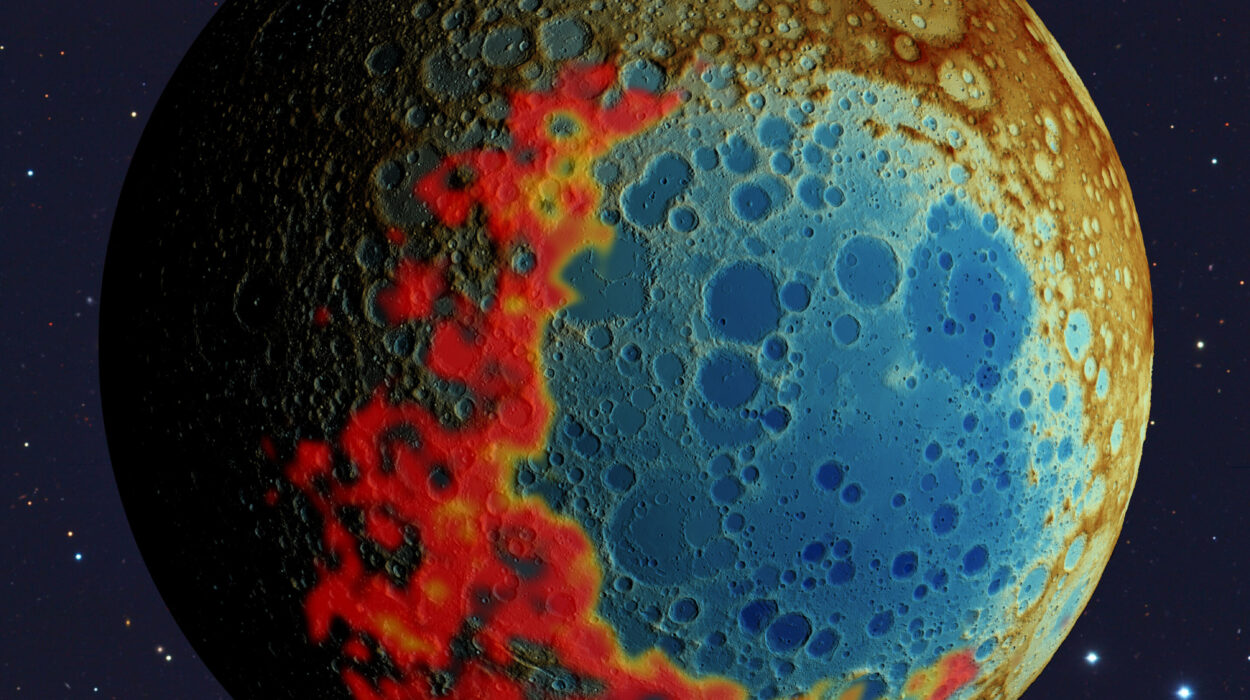

For decades, astronomers have known that something invisible is shaping the universe. Observations of galaxies and the cosmic microwave background show that there is far more matter than we can see. This unseen substance, called dark matter, outweighs ordinary matter and governs the motion of galaxies.

Yet no one knows what dark matter is made of.

“If our hypothesized dark charge is true,” says Iguaz Juan, “then we believe there could be a significant population of PBHs.” These black holes, carrying dark charge, could exist in numbers consistent with other astrophysical observations. And together, they could account for all of the missing dark matter in the universe.

In this view, dark matter is not a mysterious new particle drifting through space. It is a vast population of ancient black holes, born in the first moments after the Big Bang, quietly shaping the cosmos while occasionally announcing themselves through spectacular explosions.

The impossible neutrino may be one such announcement.

Why This Changes Everything

The arrival of a single high-energy neutrino has opened a door that physicists have been knocking on for decades. If the UMass Amherst team is right, this particle could represent the first experimental glimpse of Hawking radiation, a phenomenon that has never been directly observed. It could offer evidence that primordial black holes truly exist. It could point toward new particles beyond the Standard Model, including the dark electron. And it could finally provide a coherent explanation for dark matter, one of the greatest unsolved problems in science.

“Observing the high-energy neutrino was an incredible event,” says Baker. “It gave us a new window on the universe.”

That window looks back to the earliest moments of time, to black holes formed before stars, before galaxies, before light itself filled the cosmos. It suggests that the universe still carries messages from its birth, encoded in particles so small they almost never interact with anything at all.

One of those messages reached Earth in 2023. Against all expectations, it arrived. And in its impossible energy, it may be telling us what the universe is really made of.

Study Details

Explaining the PeV neutrino fluxes at KM3NeT and IceCube with quasi-extremal primordial black holes, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/r793-p7ct. On arXiv : DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2505.22722