Long before the rise of Rome, long before the pyramids reached their golden age, a remarkable civilization thrived quietly along the banks of the Indus River and its tributaries. This was the Indus Valley Civilization—sometimes called the Harappan Civilization—a society so advanced and so mysterious that it still puzzles historians, archaeologists, and linguists today. Hidden beneath sands and soils for nearly four millennia, its ruins tell a story of human ingenuity, resilience, and perhaps tragedy. Yet, despite its grandeur, it remains shrouded in silence, for the people of the Indus left behind no deciphered writings, only enigmatic symbols carved into seals and pottery.

The Indus Valley Civilization is one of the world’s earliest urban cultures, standing alongside Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. It flourished between roughly 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE across what is today Pakistan, northwest India, and parts of Afghanistan. With carefully planned cities, advanced sanitation, flourishing trade networks, and artistic expression, the Harappans revealed a vision of society that was astonishingly sophisticated for its time. But just as suddenly as it rose, it declined, leaving behind abandoned cities and countless unanswered questions.

To step into the Indus Valley’s story is to travel back into a world where humanity’s first experiments with city life unfolded—where innovation met mystery, and where secrets remain buried beneath the sands.

The Land of the Indus

Geography played a central role in shaping this civilization. The Indus River, one of the longest in Asia, flows from the snowy peaks of the Himalayas through arid plains into the Arabian Sea. Around 5000 years ago, the river’s basin provided fertile lands and abundant water for farming. Seasonal monsoons nourished crops, while rivers created natural highways for transport and trade.

Archaeologists believe the Indus Valley Civilization stretched across an area larger than that of Mesopotamia or Egypt—spanning over 1.25 million square kilometers. Major urban centers such as Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro anchored this expanse, while smaller towns and villages dotted the landscape. The civilization’s scale suggests a highly organized society capable of coordinating across vast distances.

But geography also held risks. The Indus River was unpredictable, prone to floods that could enrich farmland but also devastate settlements. In time, changing climate patterns, shifting river courses, and perhaps weakening monsoons may have contributed to the civilization’s decline. Yet during its peak, the Indus Valley thrived by harnessing nature’s gifts with remarkable ingenuity.

The Discovery of a Forgotten World

For centuries, the Indus Valley lay forgotten, its ruins mistaken for ordinary mounds scattered across the plains of South Asia. It was only in the 19th and early 20th centuries that archaeologists realized these mounds concealed an ancient civilization.

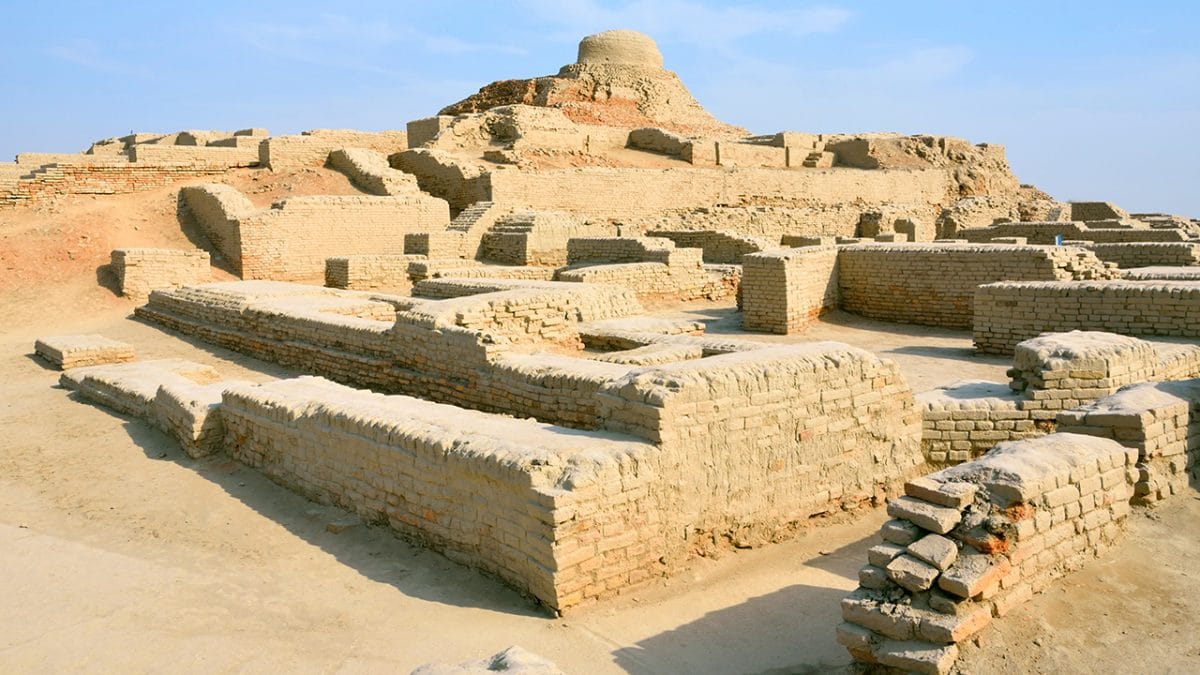

The first major discovery came at Harappa in present-day Pakistan, when workers building a railway in the mid-1800s stumbled upon bricks that had once belonged to an ancient city. These bricks, used casually in modern construction, were relics of a civilization thousands of years old. Later, in the 1920s, excavations at Mohenjo-Daro revealed an entire city, buried yet astonishingly well-preserved. Streets, wells, baths, granaries, and houses emerged from the dust, forcing historians to rewrite the story of human history.

What shocked scholars most was the sophistication of this lost civilization. These cities were not chaotic clusters of huts; they were meticulously planned urban centers that rivaled the achievements of other ancient cultures. In a sense, the Indus Valley Civilization had been hiding in plain sight—its grandeur buried beneath centuries of silence.

Cities of Order and Innovation

The cities of the Indus Valley stand as the civilization’s most striking achievement. Unlike the monumental temples and pyramids of Egypt and Mesopotamia, Harappan cities reveal a society that valued practicality, organization, and communal well-being.

Streets were laid out in grid patterns, suggesting that town planning was deliberate and centralized. Main roads intersected with smaller lanes, forming neat blocks. Houses, built of standardized baked bricks, featured courtyards, flat roofs, and private wells. Many even had bathrooms and drainage systems that connected to covered sewers—an innovation centuries ahead of its time.

The Great Bath of Mohenjo-Daro, a massive public water tank lined with bricks and sealed with bitumen, suggests a cultural emphasis on ritual bathing or communal gatherings. Nearby, large granaries point to centralized storage of food, ensuring that cities could withstand shortages.

Unlike in Egypt, where kings ruled with divine authority, or Mesopotamia, where palaces dominated cities, the Indus Valley shows little evidence of monumental rulers or grandiose temples. Instead, its urban landscape suggests a society governed more by collective order than by centralized power. This mystery—how such large cities functioned without evidence of kings or armies—remains one of archaeology’s great puzzles.

Life in the Indus Valley

What was daily life like for the people of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro? Archaeology provides tantalizing glimpses.

The Harappans were skilled farmers, cultivating wheat, barley, peas, and sesame. They domesticated animals such as cattle, buffalo, and goats, while evidence suggests they may have been among the first to grow cotton for textiles. Farmers used sophisticated irrigation techniques to harness the river’s water, supporting large populations.

Artisans thrived in the cities, crafting pottery, beads, ornaments, and figurines. The famous “Dancing Girl” bronze statue from Mohenjo-Daro reveals both artistic skill and cultural expression. Jewelry made of gold, silver, and semi-precious stones like carnelian suggests trade and personal adornment were important.

Trade was the lifeblood of the civilization. Indus merchants exchanged goods with Mesopotamia, Oman, and possibly even Egypt. Seals bearing animal motifs and undeciphered script were likely used in commerce. Archaeologists have found Indus weights and measures, standardized across cities, reflecting a regulated economy.

Children played with terracotta toys, carts, and animal figurines. Religion, though less understood, seems to have included fertility cults and reverence for animals. Clay figurines of mother goddesses and depictions of bulls suggest symbolic significance.

In short, life in the Indus Valley blended practicality with creativity, routine with ritual, in ways both familiar and alien to us today.

The Mystery of the Indus Script

Perhaps the greatest enigma of the Indus Valley Civilization is its writing system. Thousands of inscribed objects—seals, tablets, pottery fragments—have been discovered, bearing symbols that appear to form a script. Yet despite decades of effort, scholars have not deciphered it.

The script is typically short, with inscriptions rarely exceeding five or six symbols. This brevity complicates efforts to decode it. Some scholars argue it represents a full language; others suggest it may be symbolic or mnemonic rather than linguistic.

If deciphered, the Indus script could unlock vast knowledge about the civilization: its governance, religion, laws, and daily concerns. Without it, we are left with archaeology but not voices—streets but not stories, cities but not chronicles. The silence of the Indus script is both haunting and compelling, a reminder of how fragile human history can be.

A Civilization Without Kings?

One of the most striking features of the Indus Valley is what we don’t find. Unlike Mesopotamia, there are no ziggurats; unlike Egypt, no pyramids or massive statues of rulers. There are no clear signs of monarchs, dynasties, or armies.

This absence raises intriguing questions. How did such a vast civilization govern itself? Was power decentralized, perhaps resting in councils or local assemblies? Did trade guilds or religious leaders play a central role? Or was authority expressed in ways that left no monumental traces?

The lack of visible kingship has led some to describe the Indus Valley as the world’s first “egalitarian” civilization—though this may be an oversimplification. Social hierarchy certainly existed, as suggested by differences in house sizes and access to luxury goods. Yet the absence of ostentatious rulers suggests that collective order and civic planning mattered more than displays of personal power.

Decline and Disappearance

By around 1900 BCE, the Indus Valley Civilization began to decline. Cities were gradually abandoned, trade routes collapsed, and urban life gave way to smaller, rural communities. But why?

Scholars propose multiple explanations. Environmental changes likely played a major role: shifts in the monsoon weakened agriculture, rivers changed course, and floods may have damaged cities. Archaeological evidence shows signs of drought, reduced crop yields, and silted riverbeds.

Some suggest invasions by Indo-Aryan tribes contributed to the collapse, though evidence for violent conquest is limited. More likely, it was a convergence of factors—climate stress, resource depletion, and social fragmentation—that eroded the civilization’s foundations.

Unlike Egypt or Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley left no lasting dynasties or empires. Yet its legacy endured in subtle ways: agricultural practices, urban layouts, and perhaps cultural traditions that influenced later South Asian civilizations.

Legacy and Significance

Though largely forgotten for millennia, the Indus Valley Civilization holds immense significance for understanding human history. It demonstrates that complex urban societies could emerge without kings, without monumental warfare, and perhaps without rigid hierarchies. It shows that sanitation, trade, and collective planning were as crucial to civilization as temples and conquests.

The Indus Valley also reminds us of the fragility of civilizations. Despite its brilliance, it could not withstand the forces of environmental change and shifting social dynamics. Its story resonates today, as modern societies confront climate change, resource challenges, and the balance between growth and sustainability.

Most of all, the Indus Valley captivates because of its mystery. Its undeciphered script keeps its people silent, its vanished rulers invisible, its faiths and philosophies elusive. And yet, in its streets, its baths, its toys, and its ornaments, we glimpse a humanity both distant and familiar—a people who worked, traded, played, and dreamed much like ourselves.

Secrets Still Beneath the Sands

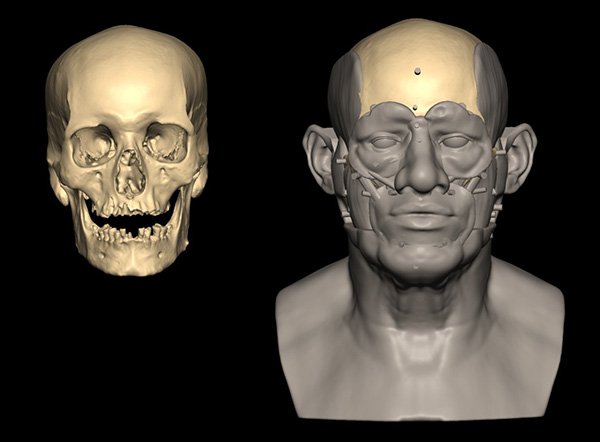

Archaeologists continue to unearth new sites, revealing fresh insights into this enigmatic civilization. Advances in satellite imaging, DNA analysis, and environmental studies promise to answer lingering questions: Who were the Harappans’ ancestors? What language did they speak? Why did they disappear so suddenly?

Perhaps one day the Indus script will be cracked, and with it, the voices of this lost civilization will finally speak. Until then, the Indus Valley remains both known and unknown—its ruins solid and tangible, its meaning elusive.

The Indus Valley Civilization is a testament to humanity’s capacity for innovation, cooperation, and resilience. Buried beneath sands for thousands of years, it whispers to us across time, reminding us that history is not just what is remembered, but also what is forgotten, waiting to be rediscovered.