In the dusty bones of our distant ancestors lies a story that’s both haunting and enlightening—a story that stretches back thousands of years, yet remains profoundly relevant today. Imagine the pathogens that once haunted prehistoric humans, lurking in the shadows of early civilizations. What diseases did they carry, and how did they shape the course of history?

In a groundbreaking study published in Nature, a team led by Eske Willerslev, professor at the University of Copenhagen and the University of Cambridge, has uncovered ancient DNA from 214 human pathogens, revealing the first-known traces of zoonotic diseases—illnesses transmitted from animals to humans. These findings, based on an analysis of over 1,300 prehistoric individuals, open a new chapter in the history of infectious diseases. The research offers a window into a time when our ancestors first began living alongside domesticated animals, forever changing the landscape of health and disease.

The study not only rewrites our understanding of how zoonotic diseases began but also offers vital insights into how these pathogens have evolved and spread over millennia. Some 6,500 years ago, humans experienced the earliest recorded encounters with zoonotic diseases—encounters that would evolve into the deadly outbreaks we know today.

The Dawn of Zoonotic Diseases: A Link to Farming and Animal Husbandry

Picture it: The first seeds of agriculture are being sown in Eurasia, and the rhythms of human life are shifting. With this change comes a significant new chapter in human existence—humans start to live closer to their domesticated animals. But this newfound proximity isn’t without its consequences. What began as a revolution in food production soon triggered the rise of diseases that would cross over from animals to humans.

“We’ve long suspected that the transition to farming and animal husbandry opened the door to a new era of disease,” says Professor Willerslev, who led the study. “Now DNA shows us that it happened at least 6,500 years ago.”

The research uncovers the fascinating—and somewhat eerie—truth: these early pathogens didn’t just cause illness; they may have played a pivotal role in shaping human history, triggering population collapses, migrations, and even genetic adaptations. As humans began to domesticate animals like cattle, sheep, and goats, they became increasingly susceptible to diseases carried by these creatures.

These findings emphasize how crucial the domestication of animals was in the development of diseases that would go on to impact human health for millennia. As early as 6,500 years ago, humans were already experiencing diseases like tuberculosis, anthrax, and various parasites—diseases that are still present today. However, the 5,000-year mark appears to be particularly important. At that time, large-scale migrations of pastoralists from the Pontic Steppe would have dramatically accelerated the spread of these diseases across vast regions.

A Revolution in Infectious Disease: The Power of Ancient DNA

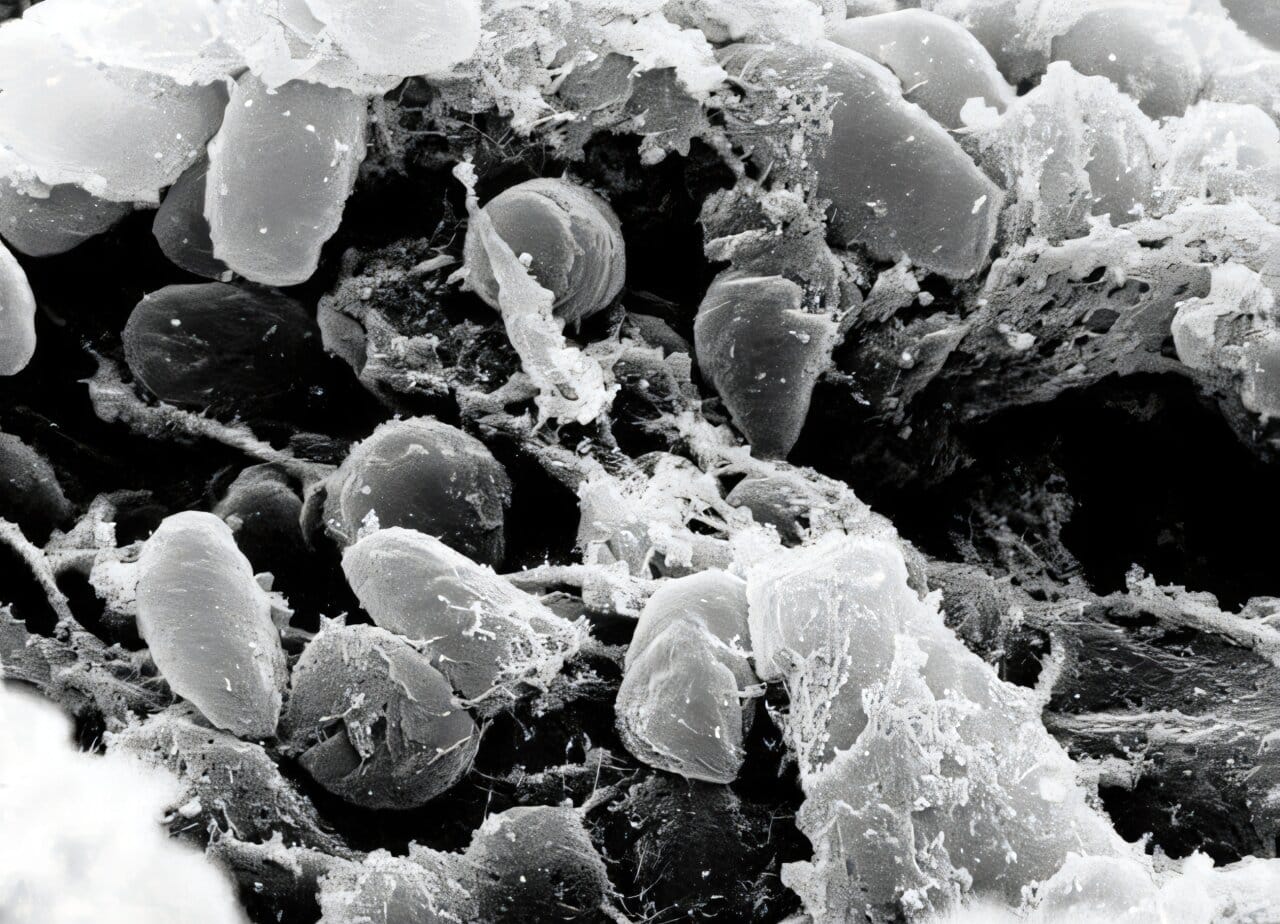

The research team’s approach was nothing short of extraordinary. They extracted ancient DNA from the bones and teeth of over 1,300 prehistoric individuals—some dating as far back as 37,000 years. These ancient remains, found in a wide range of archaeological sites across Eurasia, served as a genetic time capsule. What they uncovered was remarkable.

In total, the researchers identified 214 different pathogens. Among the most startling discoveries was the world’s oldest genetic trace of the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis, found in a 5,500-year-old sample. The bacterium that caused the Black Death, responsible for killing between one-quarter and one-half of Europe’s population during the Middle Ages, has long haunted the collective imagination. But this ancient DNA suggests that the plague was already lurking in the shadows long before the Middle Ages, affecting humans thousands of years earlier than previously believed.

But Yersinia pestis was not alone. The study also identified a host of other dangerous bacteria, viruses, and parasites that likely shaped human populations in ways we are only beginning to understand. The presence of these pathogens is a stark reminder of the ongoing relationship between humans and the diseases that have followed us for millennia.

Lessons for the Future: Preparing for Emerging Diseases

While this research offers a fascinating look at the past, it also holds powerful lessons for the future. In recent years, the world has been gripped by a pandemic—COVID-19—which, like many diseases before it, originated in animals and crossed over to humans. As our world becomes more interconnected and we encroach further into wildlife habitats, the threat of new zoonotic diseases continues to loom large.

Professor Willerslev’s team believes that understanding the history of zoonotic diseases could help prepare us for future outbreaks. “If we understand what happened in the past, it can help us prepare for the future, where many of the newly emerging infectious diseases are predicted to originate from animals,” says Associate Professor Martin Sikora, the study’s first author.

The researchers suggest that by studying past mutations in pathogens, scientists could better predict how current diseases might evolve and adapt. Some of these ancient mutations may reappear, meaning that vaccines developed to fight current diseases might need to be reevaluated to ensure they remain effective. Willerslev stresses the importance of this research for future vaccine development: “This knowledge is important for future vaccines, as it allows us to test whether current vaccines provide sufficient coverage or whether new ones need to be developed due to mutations.”

A Peek Into the Past: The Ancient Origins of Global Disease

What makes this research even more intriguing is its broader implications for understanding the evolution of human health. By examining pathogens that existed tens of thousands of years ago, we gain valuable insight into how diseases evolved and adapted over time, spreading through ancient populations and affecting everything from genetics to migration patterns.

It’s a discovery that forces us to reconsider our place in the long arc of human history. While we often think of diseases like the plague or tuberculosis as a modern scourge, they were already impacting our distant ancestors in profound ways. These early epidemics may have led to population bottlenecks, altering genetic diversity, and influencing which individuals survived to pass on their genes.

The study paints a picture of a constantly shifting landscape—one where human health is inextricably tied to the animals we live with and the diseases they carry. In this light, ancient DNA does more than just illuminate the past; it helps us navigate the future, offering clues that could help us tackle the next global health crisis before it starts.

A New Era of Disease Research

This groundbreaking study marks the dawn of a new era in disease research. As ancient DNA analysis becomes more refined, we’re bound to uncover even more about the pathogens that have shaped our history. With each new discovery, we come closer to understanding not just the diseases themselves but how they have shaped the course of human civilization.

For now, the ancient pathogens of Eurasia remain silent, preserved in the bones of our ancestors. But their story is far from over. As we look ahead, the study of ancient DNA offers an invaluable tool for understanding the origin, spread, and evolution of infectious diseases—and how they may continue to shape our future.

Reference: Martin Sikora, The spatiotemporal distribution of human pathogens in ancient Eurasia, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09192-8. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09192-8