About 120,000 years ago, long before cities or writing or the familiar rhythm of modern life, the Levant was a crossroads where different human species brushed past each other. Neanderthals, Homo erectus–like populations, and the earliest Homo sapiens shared the same landscapes, breathed the same dry-season air, and watched the same herds of wild cattle move across the plains. Yet their lives, it now seems, unfolded along very different paths.

A new study from the Nesher Ramla karst depression adds a vivid and surprisingly intimate glimpse into how these encounters may have shaped human history. Instead of dramatic mass hunts or grand communal drives, the extinct relatives of modern humans practiced something far quieter and more deliberate: the selective hunting of wild cattle, carried out one or two animals at a time.

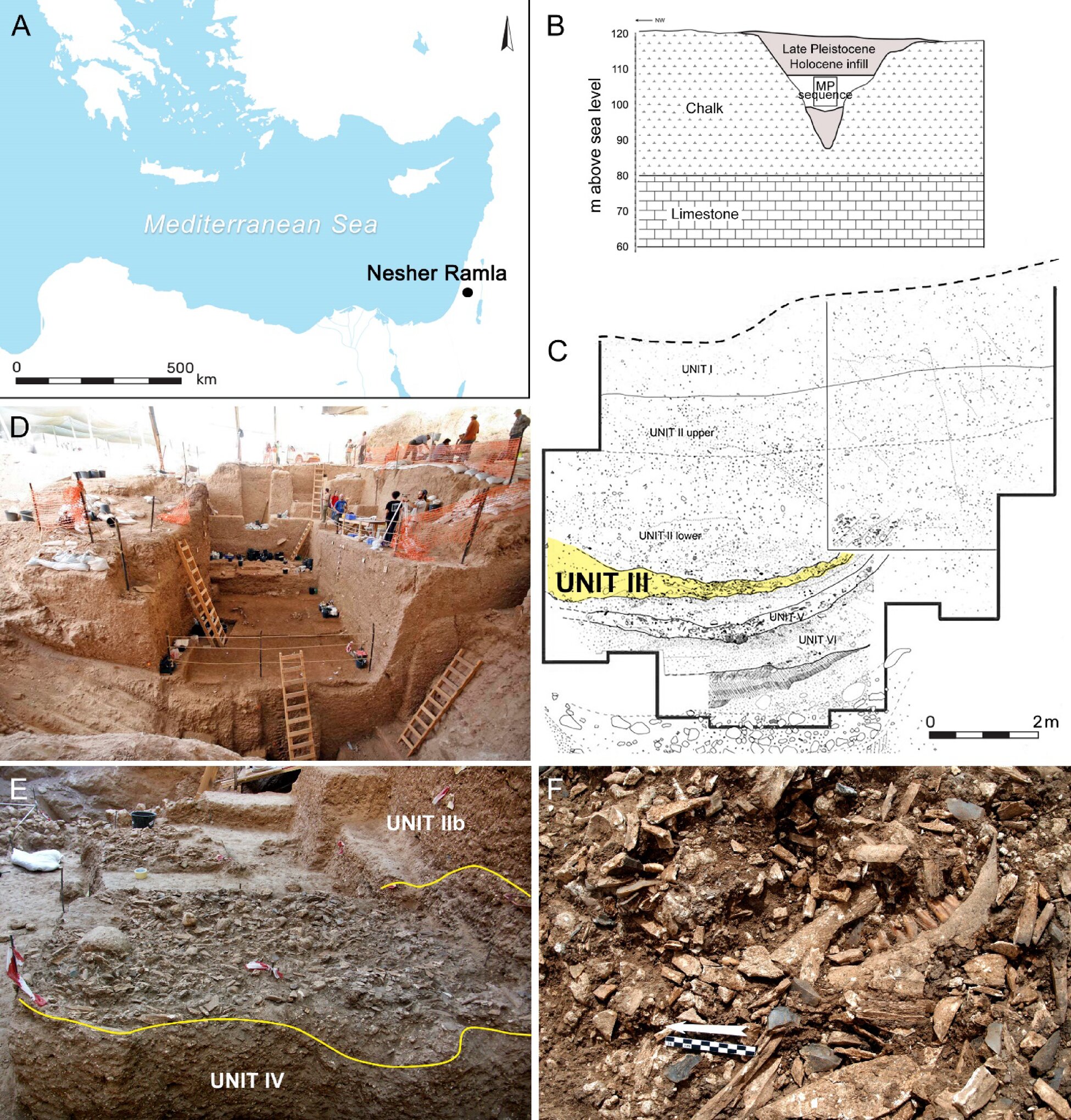

A Landscape Layered with Ancient Meetings

The Nesher Ramla site is more than a fossil deposit; it is a time capsule where layers of the Middle Paleolithic world lie stacked like pages in a book. Archaeologists excavating deposits dating back about 120,000 years discovered something striking: the bones of aurochs, the massive wild ancestors of modern cows, collected in one place with unmistakable signs of hunting and butchering.

These bones did not tell the story of a frenzied kill site where hunters drove entire herds into pits or traps. Instead, they spoke of patience. Precision. A deliberate choice of prey. The research team found that archaic humans consistently targeted prime-aged female aurochs. Their remains appeared not as a single overwhelming heap but as evidence of “isolated hunting incidents carried out in small batches, likely during the dry season.”

The immediate implication was clear. These people were not mass hunters. But the deeper implications were far richer.

Clues Hidden in Bones, Teeth, and Time

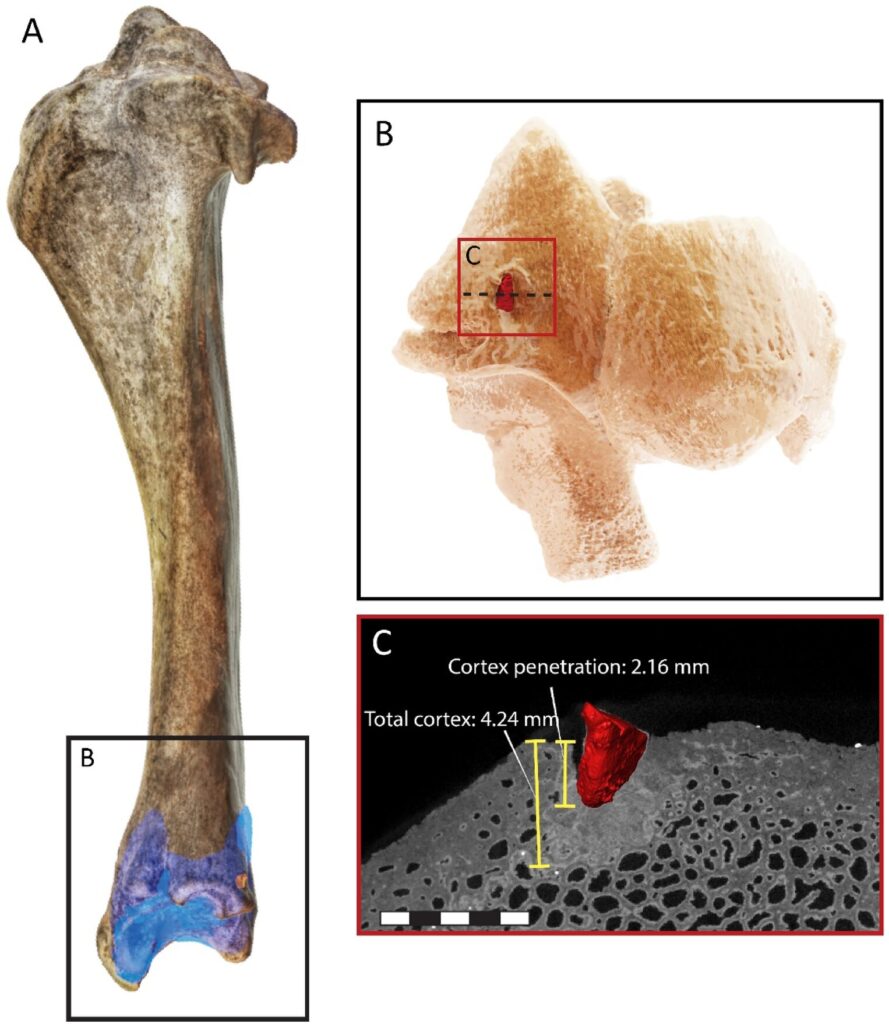

To reconstruct who hunted what, and how, the team examined the subtleties within the auroch remains. Bone fusion patterns and sexual dimorphism offered information about age and sex, revealing an unmistakable bias toward prime-aged cows. This alone signaled a careful, selective approach rather than an indiscriminate harvest of entire herds.

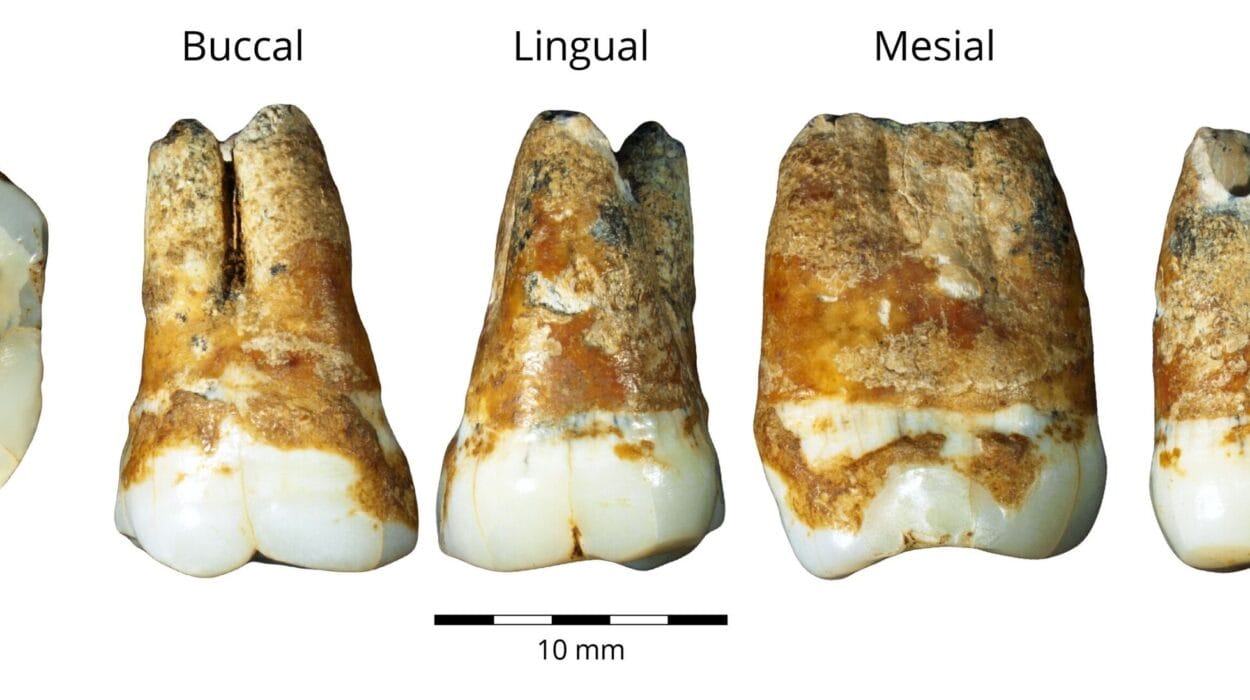

But the teeth told even more. Their surfaces carried the microscopic scars of an animal’s last meals. Because “a look at the microwear and tear on the teeth… revealed that the aurochs were killed during dry season when they had to rely on evergreen woody leaves and small twigs,” the researchers could pinpoint the season of the hunts.

Even deeper within the teeth, isotopic signatures preserved the chemical fingerprints of the regions the animals had roamed. These distinctive isotopic ratios showed that the animals came from different herds and different landscapes. It was an unmistakable signal: no single herd had been driven en masse to slaughter. As the study states, “isotopic analysis of the aurochs’ teeth revealed that they came from different herds and locations, thus refuting the mass hunting hypothesis.”

This was not industrial-scale hunting. It was personal, intentional, and episodic.

Reconstructing Ancient Lives from Hunting Patterns

Because direct evidence of archaic human social structure is scarce, researchers often rely on indirect clues. Hunting strategies can reveal how many individuals planned and acted together, how food was shared, and how groups coordinated during crucial survival tasks.

A key question hangs over the Middle Paleolithic: Did archaic humans live in small, isolated groups while modern humans formed broader, more interconnected communities? Many scholars favor this idea, and the Nesher Ramla findings strengthen that interpretation.

The logic is straightforward. Mass hunting requires far more than brute force. It demands communication across distances, cooperation among many people, and cultural norms that support large-scale food sharing. If archaic humans had organized themselves this way, the remains at Nesher Ramla would likely have shown signs of mass-kill events or coordinated drives. Instead, the evidence points in the opposite direction.

The study’s authors used this reasoning as a way to test long-standing hypotheses about social organization. They noted that “mass hunting… would require high levels of communication, cooperation and food sharing behavior among a large group of people.” Its absence here, especially in a site where archaic and modern humans may have directly interacted, suggests that these older species maintained the small, dispersed communities already suspected.

Meanwhile, Homo sapiens are known to have engaged in mass hunting around 50,000 years ago. While the researchers wondered whether such strategies might have deeper roots, the Nesher Ramla evidence showed no sign of earlier emergence. The patterns instead reinforced the view that archaic humans navigated life with fewer collaborators, fewer connections, and fewer opportunities to pool knowledge or resources.

At the Edge of Contact, Two Strategies Diverged

Nesher Ramla Unit III is significant not just for its age but for its context: it may be one of the regions where archaic humans and modern humans met face-to-face. In this shared space, two human strategies stood side by side.

On one hand were archaic humans whose hunting behavior suggests a careful but solitary rhythm. They chose specific prey. They hunted in ones and twos. They operated in small, likely scattered communities.

On the other hand were Homo sapiens, who, even if not yet engaged in mass hunting at this precise moment, were evolutionarily moving toward greater coordination and broader networks. Over tens of thousands of years, these larger interconnected societies may have offered advantages in resilience, knowledge exchange, and resource management.

This comparison supports the idea that archaic humans, despite their skill and adaptability, may have been at a disadvantage when living alongside Homo sapiens. As the study notes, “this difference may have increased modern humans’ chances of survival in regions where both groups co-existed.”

Why This Research Matters

Understanding how ancient humans hunted may seem like a narrow detail, but it illuminates one of the biggest questions in human evolution: why did our species thrive while others dwindled?

The Nesher Ramla study offers evidence that the answer may lie not only in biology but in social structure. If archaic humans lived in small, fragmented groups, while Homo sapiens built broader networks and shared information more widely, these differences could have shaped how each species responded to environmental challenges, resource scarcity, and competition.

These findings also remind us that evolution is not a straight line or a simple contest of strength. Often, it is culture—how people organize, cooperate, and innovate—that determines who survives. The research underscores that “further investigation is needed,” especially because other sites may yet reveal more complex hunting strategies in the Levant. But for now, the evidence from Nesher Ramla deepens our understanding of a pivotal moment when multiple human species shared the same land but walked into different futures.

In the bones of ancient aurochs, we find not just the story of a hunt, but the echo of a turning point in human history.

More information: Reuven Yeshurun et al, Archaic humans in the Middle Palaeolithic Levant conducted planned and selective intercepts of aurochs, but not mass hunting, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-26274-9