For nearly a hundred years, it sat quietly in a museum collection, barely noticed, barely remembered. It was tiny, no longer than a finger, light enough to disappear in a palm. When archaeologists first recorded it in the 1920s, they gave it a modest, almost dismissive description: a little copper awl, wrapped with some leather thong. Then they moved on.

But history has a habit of circling back.

A new study has returned to this overlooked object, excavated long ago from a cemetery at Badari in Upper Egypt, and listened more carefully. What researchers from Newcastle University and the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna discovered is startling in its implications. This small copper-alloy tool is now identified as the earliest known rotary metal drill from ancient Egypt, dating to the Predynastic period, in the late fourth millennium BCE, long before the first pharaohs rose to power.

What once looked like a simple awl now tells a much richer story about invention, skill, and the quiet brilliance of everyday technology.

The Grave and the Man Who Took a Tool With Him

The drill was found in Grave 3932, the burial of an adult man. We do not know his name, his profession, or the details of his life. But someone chose to place this tool beside him in death, suggesting it mattered. Tools are intimate things. They carry the memory of hands, of repeated motions, of work done day after day.

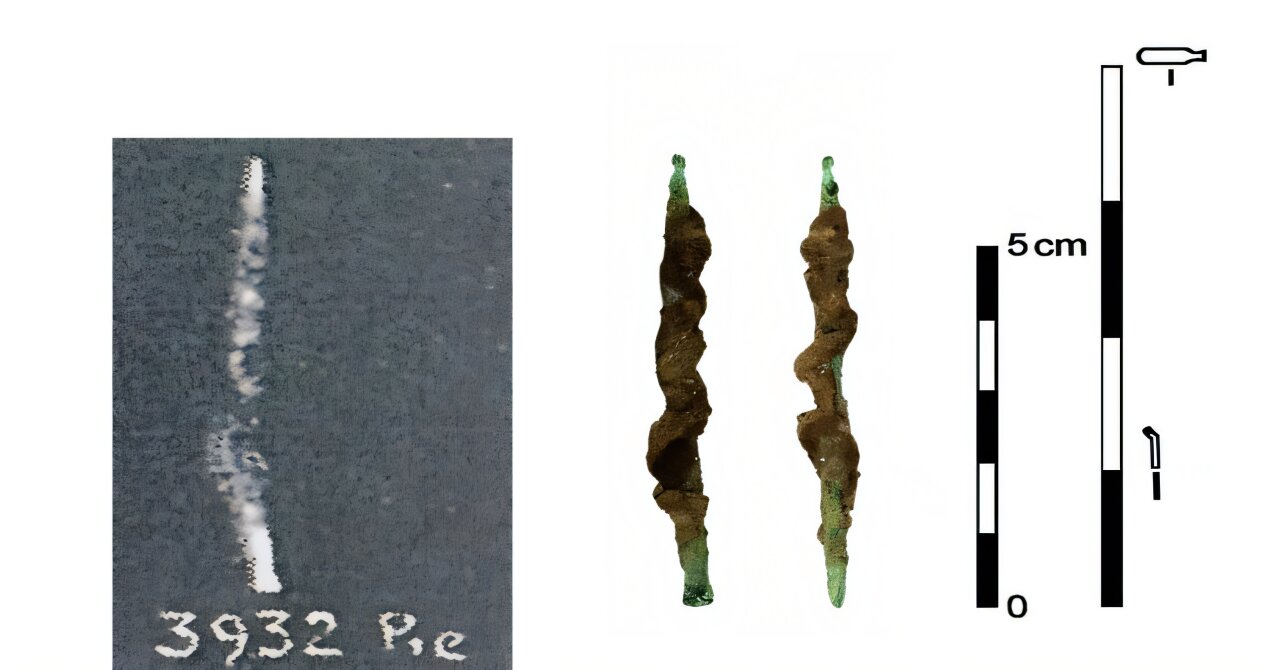

Cataloged as 1924.948 A and now held at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, the object measures just 63 millimeters long and weighs about 1.5 grams. Its size made it easy to miss. Its meaning made it easy to misunderstand.

For decades, no one thought to look closer.

Looking Again, This Time Through a Lens

When the research team examined the object under magnification, the story changed. The surface revealed fine striations, subtle but unmistakable. The edges were rounded, not sharp. The working end showed a slight curvature.

These marks are not what you would expect from a tool used to poke or puncture by hand. They are the signatures of rotary motion, created when an object spins rapidly against another material. In other words, this was not an awl. It was a drill.

This distinction matters more than it may first appear. Rotary drilling represents a leap in mechanical understanding. It allows for faster work, greater control, and more precise results. It transforms what a craftsperson can do.

Six Fragile Loops That Changed Everything

Perhaps the most delicate and astonishing part of the find is not metal at all.

Wrapped around the shaft are six coils of extremely fragile leather thong. Organic materials like leather rarely survive from such deep antiquity. Yet here it was, clinging to the tool across millennia.

The researchers argue that this leather is the remnant of a bowstring, once part of a bow drill. In this setup, a string is wrapped around the drill shaft and attached to a bow. Moving the bow back and forth spins the drill rapidly, much like an ancient hand-powered version of a modern drill.

This configuration would have allowed the user to generate consistent speed and pressure, far beyond what twisting a tool by hand could achieve. It turns a simple piece of metal into a sophisticated machine.

Everyday Technology Behind Ancient Wonders

Dr. Martin Odler, lead author of the study and Visiting Fellow at Newcastle University, emphasizes why this matters. Ancient Egypt is often celebrated for its monumental achievements, stone temples, painted tombs, and glittering jewelry. But behind all of that beauty stood humble tools.

The drill was one of the most important. It enabled people to pierce wood, stone, and beads, supporting everything from furniture-making to ornament production. Without reliable drilling, much of what defines ancient Egyptian material culture would not have been possible.

This re-analysis shows that Egyptian craftspeople had mastered controlled rotary drilling more than two millennia earlier than some of the best-preserved drill sets known from later history.

Earlier Than Anyone Expected

Bow drills are well documented in much later periods of Egyptian history. Surviving examples from the New Kingdom, in the middle to late second millennium BCE, show similar tools in use. Tomb scenes from the area of modern-day Luxor depict craftsmen drilling beads and woodwork with confidence and precision.

Until now, this level of mechanical sophistication was not firmly anchored in the Predynastic period. The Badari drill pushes that timeline back dramatically. It suggests that the knowledge behind these tools did not suddenly appear alongside kings and monumental architecture. It was already present, refined through generations of hands-on experimentation.

A Metal Recipe That Raises New Questions

The story deepens when chemistry enters the picture.

Using portable X-ray fluorescence analysis, the team examined the composition of the drill. It is not made of simple copper. Instead, it contains arsenic and nickel, with notable amounts of lead and silver.

According to co-author Jiří Kmošek, this combination would have produced a harder and visually distinctive metal. The presence of silver and lead may indicate deliberate alloying choices, suggesting that the maker understood how different elements could change the properties of metal.

Even more intriguingly, this unusual recipe may hint at wider networks of materials or know-how, potentially linking Egypt to the broader ancient Eastern Mediterranean during the fourth millennium BCE. The tool does not just speak of local skill. It whispers of connection.

When Museum Shelves Become Time Machines

This discovery did not come from a new excavation or a dramatic dig. It came from a museum shelf.

The study is linked to the EgypToolWear project, which focuses on understanding ancient tools through microscopic wear and careful re-examination. The Badari drill shows how much knowledge still lies hidden in collections assembled long ago, often described briefly and then set aside.

A single line in a publication from the 1920s failed to capture the object’s true nature. Today, that same object preserves evidence of early metalworking, mechanical innovation, and even organic material that reveals how the tool was powered and used.

It is a reminder that archaeology is not only about finding new things, but about learning how to see old things differently.

Why This Discovery Matters

This small drill changes how we think about early Egyptian technology. It shows that mechanical sophistication did not wait for pharaohs, pyramids, or written history. It emerged quietly, through the needs of craftspeople solving practical problems.

By demonstrating that bow drill technology existed in the late fourth millennium BCE, the research reshapes timelines and challenges assumptions about when complex tools became part of daily life. It highlights the intelligence embedded in ordinary work and the creativity of people whose names we will never know.

Most of all, it reminds us that progress does not always announce itself with grandeur. Sometimes, it survives as a fragile coil of leather around a tiny piece of metal, waiting patiently for someone to look again.

Study Details

The Earliest Metal Drill of Naqada IID Dating, Egypt and the Levant (2026) DOI: 10.1553/AEundL35s289. www.austriaca.at/?arp=0x0041300e