The rugged valleys and soaring peaks of the Southern Caucasus have witnessed millennia of human history — from the rise of ancient kingdoms to the spread of Christianity, from bustling trade routes to the movements of empires. Now, a groundbreaking international study has opened a new chapter in our understanding of this crossroads of civilizations.

An international team of scientists from Germany, Georgia, Armenia, and Norway has analyzed ancient DNA from 230 individuals recovered from 50 archaeological sites across Georgia and Armenia. By piecing together these genetic clues, the researchers have reconstructed a sweeping 4,000-year history of the region — revealing stories of continuity, migration, and cultural transformation.

The work, published in Cell, was conducted within the Max Planck-Harvard Research Center for the Archaeoscience of the Ancient Mediterranean, co-directed by Johannes Krause, Director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, and Philipp Stockhammer, Professor at Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich.

A Deeply Rooted Ancestry

One of the study’s most surprising revelations is just how stable the population’s genetic makeup has been over the centuries. From the Early Bronze Age (around 3500 BCE) to the centuries following the Migration Period (about 500 CE), the Southern Caucasus retained a remarkably constant ancestry profile.

“The persistence of a deeply rooted local gene pool through several shifts in material culture is exceptional,” says population geneticist Harald Ringbauer, whose team at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology led the analysis. “This stands out compared to other regions across Western Eurasia, where many cultural changes were accompanied by major movements of people.”

In other words, while pottery styles, burial practices, and political borders shifted over the millennia, the genetic foundation of the local population endured — an unbroken thread through the fabric of history.

Bronze Age Encounters

Yet, this continuity does not mean the Southern Caucasus was isolated. The researchers found genetic traces of interactions with neighboring peoples, especially during the later phases of the Bronze Age. Some ancestry from Anatolia and the Eurasian steppe pastoralists entered the region during this period, coinciding with innovations in technology, shifts in economic systems like mobile pastoralism, and changes in burial traditions.

These migrations were not sweeping population replacements but smaller waves of interaction. Following the Bronze Age, the population grew, and genetic markers from newcomers often appear as brief episodes or in isolated individuals — a testament to a region that could absorb outside influences without losing its deep-rooted identity.

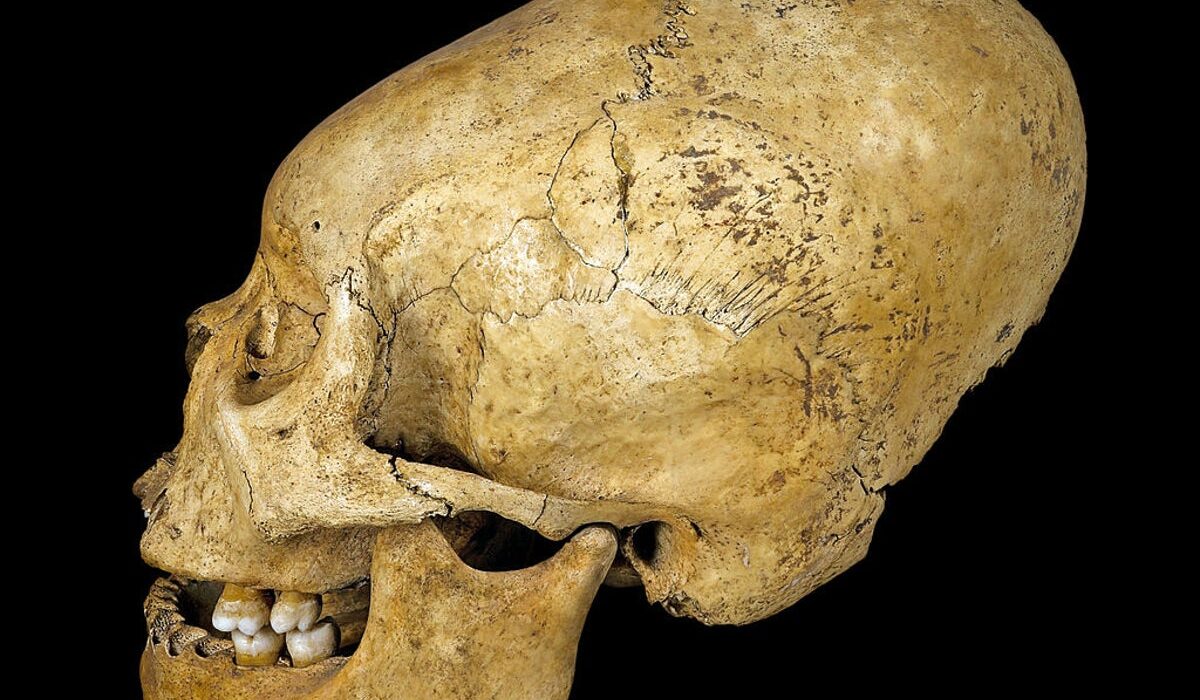

The Mystery of Deformed Skulls

One of the most visually striking discoveries came from early medieval burials in the territory of the ancient Iberian Kingdom in present-day eastern Georgia: intentionally deformed skulls. For decades, archaeologists believed this practice was introduced by nomadic groups from the Central Eurasian Steppe, such as the Huns or Avars.

Geneticist Eirini Skourtanioti, the study’s lead author, explains: “We identified numerous individuals with deformed skulls who were genetically Central Asian, and we even found direct genealogical links to nomadic groups like the Avars and Huns. But the surprise was that most of these individuals were locals, not migrants.”

The finding reveals that cranial deformation — a dramatic reshaping of the skull during infancy — was not just a mark of foreign origin. It was a cultural practice adopted by local people, likely as a result of contact with migrating groups.

Liana Bitadze, head of the Anthropological Research Laboratory at Tbilisi State University, sees this as a turning point in understanding the custom. “In the past, we addressed this question through comparative morphometric analyses,” she says. “Now, ancient DNA gives us an entirely new line of evidence — and more definitive answers.”

Cities as Cultural Crossroads

The study also sheds light on the later periods of Southern Caucasus history, especially during Late Antiquity. As cities and early Christian sites emerged in eastern Georgia, they became hubs of diversity, drawing people from across the region and beyond.

“Historical sources mention how the Caucasus Mountains served both as a barrier and a corridor for migration,” says Xiaowen Jia, co-lead author and Ph.D. researcher at Ludwig Maximilians University Munich. “Our study shows that in Late Antiquity, increased individual mobility was a defining feature of urban life.”

These findings reinforce the view of the Caucasus not as a remote backwater, but as a vibrant, interconnected frontier — a place where cultures met, mingled, and transformed.

Rewriting the Region’s Genetic History

For archaeogenetics, the Southern Caucasus has long been a blind spot, overshadowed by studies of Western Europe, the Near East, and the Eurasian steppe. This new research sets a high standard for the region, combining large-scale genetic data with archaeological context to offer a nuanced, human-scale portrait of the past.

It shows a land where traditions could persist for thousands of years, yet where cultural innovations — from herding practices to skull-shaping — flowed in through the steady currents of human contact. It is a reminder that history is not only written in stone monuments and ancient texts, but also in the genetic code quietly carried by every person who has ever lived.

More information: The Genetic History of the Southern Caucasus from the Bronze Age to the Early Middle Ages: 5000 years of genetic continuity despite high mobility, Cell (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.07.013