Long before the rise of cities or written language, small bands of humans began to settle down. They planted seeds, raised animals, and built the first villages — modest clusters of mud-brick homes that would become the foundation of civilization. But what did it mean to belong to one of these early farming communities? How did people move, marry, and connect in a world just discovering permanence?

A team of archaeologists has recently brought this distant world into sharper focus. By analyzing the chemical signatures preserved in human teeth found across ancient Syria, they have revealed how the world’s first farmers built communities, how they moved across the land, and how they welcomed outsiders into their midst. Their discoveries do more than illuminate the lives of people who lived 10,000 years ago — they offer a mirror, showing how humanity’s earliest roots of cooperation, kinship, and inclusion began to grow.

Reading Stories Written in Teeth

Archaeologists often say that bones tell stories. But teeth, it turns out, can whisper secrets that bones cannot. In this groundbreaking study, led by Dr. Eva Fernandez-Dominguez of Durham University, researchers analyzed strontium and oxygen isotopes from the tooth enamel of 71 individuals. These remains spanned the entire Neolithic period — roughly from 11,600 to 7,500 years ago — and came from five archaeological sites scattered across what is now modern Syria.

Each person’s teeth carried the imprint of the place where they grew up. The ratio of strontium and oxygen isotopes reflects the unique geological and climatic fingerprint of a region, absorbed through the water and food a person consumed during childhood. By comparing these isotopic patterns, the team could tell whether someone had spent their early years in the same area where they were buried or had moved there later in life.

The result was a map not of territories, but of movements — invisible trails of migration, exchange, and settlement drawn across the ancient landscape.

Settling Down: The Birth of the Village

The Neolithic period marks one of the greatest turning points in human history: the shift from nomadic hunting and gathering to settled farming life. In the fertile valleys of the Near East, including the region that is now Syria, people began to cultivate wheat and barley, domesticate sheep and goats, and build permanent homes.

The isotope analysis revealed that in the earliest stages of the Neolithic, people were still highly mobile. Communities were small and fluid, with groups moving across the land as they experimented with early forms of agriculture. But as the centuries passed and permanent villages took root, that changed dramatically.

The data showed that most individuals buried in these later settlements had grown up locally. They were born, lived, and died in the same place. Over generations, people began to form deep, enduring ties to their land and to each other. Villages became more than just clusters of homes — they became symbols of identity and belonging.

Women on the Move

One of the study’s most fascinating insights came from the discovery that women were more likely than men to move between communities in the later Neolithic. While most men appeared to have been born and raised in the same village, the isotope signatures in several women’s teeth indicated that they had grown up elsewhere.

This pattern suggests the rise of patrilocal traditions — social systems in which women left their birth communities to marry and join their husbands’ families. Such practices are known from many later cultures around the world, but this research shows that their roots stretch deep into prehistory.

There is also a biological logic behind this social pattern. By encouraging women to marry outside their natal villages, communities could reduce the risk of inbreeding, introducing genetic diversity and strengthening the population’s resilience. What might seem like a personal decision — who one marries, where one moves — was, at its core, an evolutionary strategy that helped early societies thrive.

Shared Graves, Shared Lives

The study’s power lies not only in chemical analysis but also in how it connects science to human experience. When the researchers compared isotopic data with burial patterns and funerary rituals, they found something remarkable.

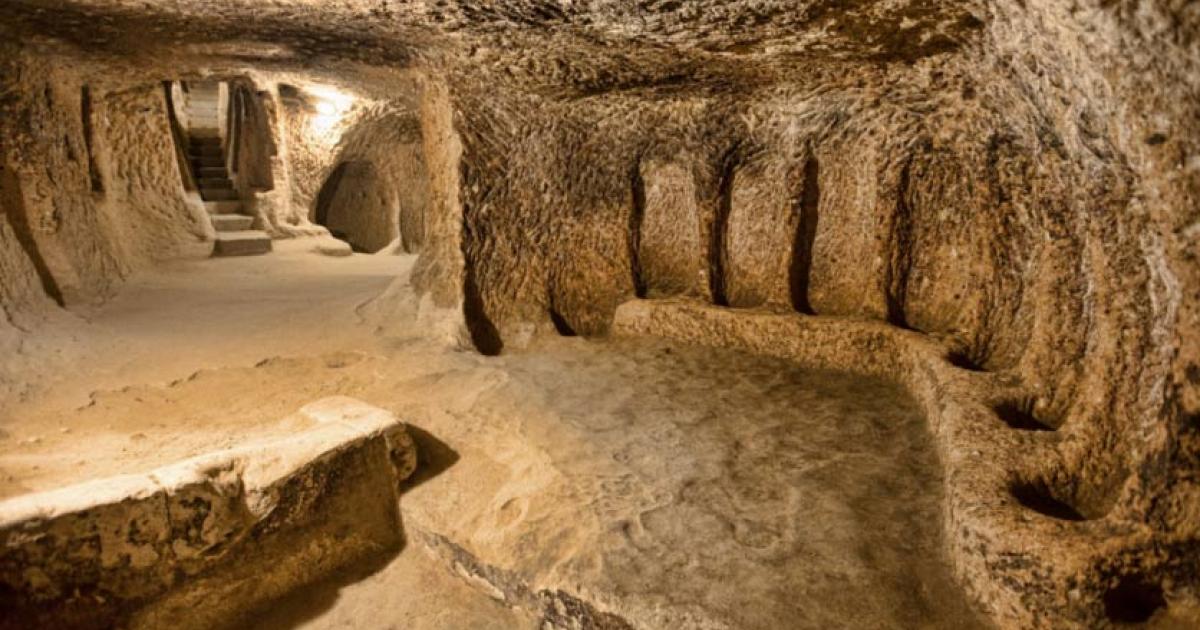

At sites like Tell Halula, a Neolithic settlement near the Euphrates River, people were often buried within the very houses where they had lived. Layers of human remains were found beneath the floors, suggesting that generations of family members — or perhaps community members — rested together in death.

But isotope analysis revealed that not all of these individuals were locals. Some had grown up in distant regions before joining the community. Yet, in burial, there was no distinction. Local and non-local individuals were treated the same — sometimes with elaborate funerary rites and special burial positions, such as being seated upright.

This equality in death suggests equality in life. Outsiders were not marginalized but welcomed, woven into the social and spiritual fabric of the village. Even those who came from afar were granted the same honor, the same care, and the same place in the ancestral home.

The Open Villages of Early Farmers

In the modern imagination, ancient villages might seem insular or isolated — small pockets of humanity clinging to survival. But this research paints a different picture. Early farming communities were surprisingly open and inclusive.

The isotope data showed that while most people stayed local, outsiders were common and accepted. At several sites, local and non-local individuals were buried side by side in the same cemeteries, often with similar grave goods and under the same conditions. There was no clear sign that newcomers were treated as strangers or outsiders.

This openness may have been essential for survival. Farming was a new and uncertain endeavor — crops could fail, herds could die, and environmental conditions could shift. By maintaining flexible and inclusive social networks, these early communities could share knowledge, labor, and resources. Welcoming newcomers wasn’t just kind; it was smart. It brought new skills, new connections, and new lifelines.

The Science Behind the Findings

To uncover these insights, the team combined multiple strands of evidence. The strontium isotope ratios in tooth enamel reflected the geological signature of the region where each individual spent their childhood. The oxygen isotopes, meanwhile, captured variations in local water sources linked to climate and altitude.

These chemical clues were then compared against local environmental data to determine each person’s likely origin. Skeletal analysis added another layer of understanding — providing information about age, sex, health, and burial context.

By merging these approaches, the researchers could reconstruct an intricate picture of mobility, social organization, and community life across thousands of years. What emerged was not a static scene but a dynamic portrait of how the first farmers navigated a changing world — both physically and socially.

The Dawn of Social Identity

What does it mean to belong? The Neolithic villagers of Syria were among the first people in human history to grapple with that question in a settled world. Before farming, belonging was defined by movement — by shared paths, shared hunts, shared migrations. But once people began to stay in one place, new identities emerged.

The study’s findings suggest that these early farmers built communities rooted in shared land and shared memory, yet flexible enough to include newcomers. Their villages were not fortresses but living organisms, constantly adapting, growing, and integrating.

In their graves, we see the reflection of their values. The equal treatment of locals and outsiders in death speaks of a social order based not on birthplace but on participation — on being part of the rhythm of daily life, the planting and harvesting, the shared rituals of the living and the dead.

A Window into Humanity’s First Home

Standing in a Neolithic village 10,000 years ago, one might have heard the low hum of conversation around a communal hearth, the laughter of children playing near the fields, the rhythmic thud of grinding stones. Life was hard, but it was shared.

Every tooth, every bone uncovered by archaeologists tells a fragment of this ancient story — a story of connection, resilience, and adaptation. The people of these early villages were not so different from us. They too loved, mourned, and dreamed. They built homes, formed families, and found meaning in community.

Their openness to newcomers reminds us that inclusion has always been part of our species’ success. The instinct to welcome, to connect, to build together — that, perhaps, is humanity’s oldest tradition.

The Legacy of the First Farmers

The discoveries from this study, published in Scientific Reports, reach far beyond the dusty soils of ancient Syria. They help redefine what it means to be human. Our ancestors were not merely survivors; they were innovators of social life. They created the first systems of belonging, laying the groundwork for the complex societies that would follow.

In understanding them, we better understand ourselves. The same forces that shaped those early villages — mobility, marriage, migration, and inclusion — continue to shape our world today. In an age of borders and displacement, their story is a reminder that openness and cooperation are not modern ideals; they are ancient ones.

The first farmers of the Neolithic built more than villages. They built the human heart of community — a legacy that still beats within us all.

More information: Jo-Hannah Plug et al, Strontium and oxygen isotope analysis reveals changing connections to place and group membership in the world’s earliest village societies, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-18134-3