At the edge of the Egyptian desert, where the Red Sea wind brushes ancient stone and the sun bleaches every footprint into silence, archaeologists have uncovered a story no one expected. Berenike, once a bustling Roman port, has offered up many artifacts over the years. But nothing has stirred curiosity quite like the discovery of dozens of carefully buried monkeys.

These small primates were not wild creatures stumbled upon by chance. They were companions, status symbols, and in some cases, beloved pets of Roman military elites. Their presence in this isolated port reveals a world in which luxury traveled across oceans, and prestige could be measured by the creature perched on a general’s shoulder.

Where Monkeys Were Treated Like Nobility

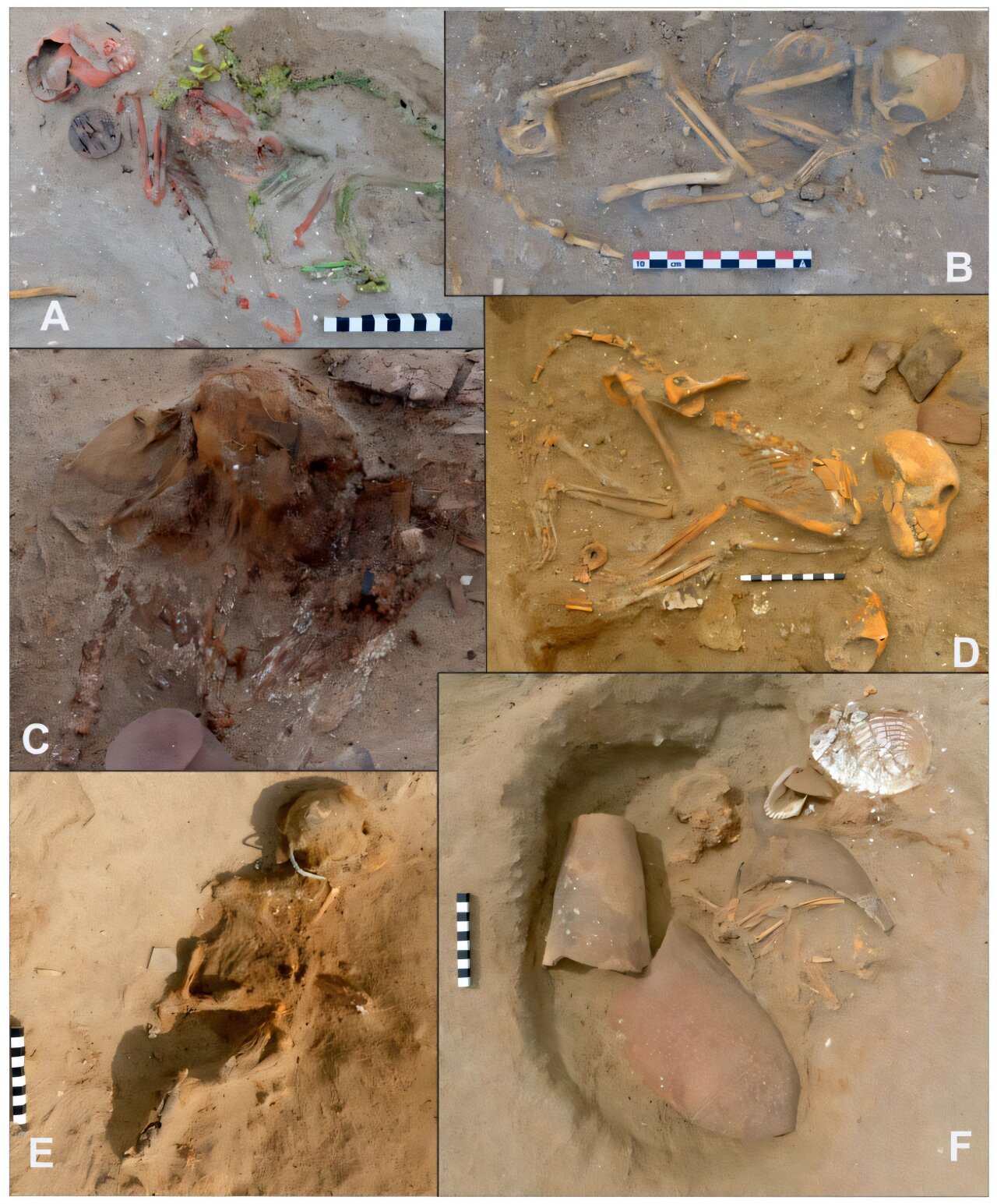

The cemetery that unlocked this story sits just outside the ancient city’s edge. Found in 2011, it has since yielded nearly 800 animal burials, but the thirty-five monkeys resting there have captured the most attention. Their bones date to the first and second centuries CE, the same period when high-ranking Roman military personnel were posted in Berenike.

These were not local species. According to the study’s authors, most of the bones belonged to macaques from India. This single detail rewrites what historians knew about ancient trade. Never before had there been physical proof that live animals were transported all the way from India to Roman Egypt.

As the researchers wrote, “The Berenike burials of monkeys of this species are the first unequivocal indication of organized importation of non-human primates from beyond the ocean.”

The conclusion is striking. Someone went to enormous effort to bring these animals across dangerous sea routes, not for practical use, but as symbols of prestige.

The Luxury Goods Buried With Silent Companions

What makes these burials especially revealing is not just the monkeys themselves but what they were laid to rest with. Nearly forty percent of the monkey graves contained grave goods. That number is astonishing when compared to the roughly three percent of cats and dogs that received the same treatment.

Monkeys were buried with restraining collars, bowls of food, and dazzling objects such as iridescent shells. These were offerings suggesting affection, care, and a desire to honor them in death. Some graves held an even stranger surprise. A few monkeys had their own pets, like piglets or kittens, nestled beside them in the sand. This was not mere disposal. This was ceremony.

The authors note that “Owning monkeys may have been an element of identity, a distinct marker of one’s elite place in local society.”

In other words, to own a macaque in Berenike was to declare yourself wealthy, connected, and unmistakably elite.

When Prestige Meets Harsh Reality

Yet not every part of the story is glamorous. Two rhesus macaque skulls showed signs of malnutrition. Their teeth and bone development hinted at diets lacking fresh fruits and vegetables, staples that primates need to survive and thrive.

The researchers do not believe this was cruelty. Instead, it reflects the challenge of keeping such animals alive in one of the most isolated Roman outposts. Berenike was far removed from major farming regions. Supplying fresh produce there was difficult even for humans, let alone exotic pets from across the ocean.

The result was a paradox. Monkeys were treasured enough to be buried with honors, yet their daily care was hindered by the limits of geography.

An Ancient Story With Modern Echoes

The discoveries at Berenike provide a vivid look at ancient Roman life. The port may have been remote, but its inhabitants carved out a world of wealth, display, and personal identity that feels surprisingly familiar. The desire to own exotic pets, to display rare possessions, and to stand apart from the ordinary is a trait that stretches across centuries.

These burials reveal more than the affection or ambition of individual Romans. They map the reach of ancient trade, the complexities of cultural identity, and the lengths elites would go to shape how they were seen. A monkey in Berenike was not simply an animal. It was a statement.

Why This Research Matters

The Berenike monkey burials transform our understanding of ancient Rome’s global connections. They provide the first physical evidence of live primate importation across the Indian Ocean. They show that Roman elites expressed identity not only through architecture, clothing, or public events but through living companions whose presence required extraordinary effort to obtain and maintain.

These discoveries remind us that history is not only built from battles and politics but from the quiet traces of daily life. Every shell placed in a monkey’s grave and every collar clasped around a tiny neck tells a human story. It is a story of aspiration, affection, cultural expression, and the universal desire to stand out in the world.

Two thousand years have passed, yet the impulse remains recognizable. The ancient Romans of Berenike lived at the edge of an empire, but their dreams of status, luxury, and connection reached far beyond the horizon.

More information: Marta Osypińska et al, A centurion’s monkey? Companion animals for the social elite in an Egyptian port on the fringes of the Roman Empire in the 1st and 2nd c. CE, Journal of Roman Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1017/s1047759425100445