A quiet cornfield in southern Sulawesi, Indonesia, has yielded a message from the deep past—seven tiny stone fragments, sharp and weathered, tucked away in the layers of ancient sandstone. At first glance, these flakes of stone may seem unremarkable. But to scientists, they are astonishing.

According to a groundbreaking study published in Nature, these tools—painstakingly excavated by a team led by Budianto Hakim of Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) and Professor Adam Brumm from the Australian Research Center for Human Evolution at Griffith University—date back at least 1.04 million years. The implications of this discovery are nothing short of extraordinary: early humans made a major deep-sea voyage to reach Sulawesi long before we ever imagined.

The Ancient Puzzle of the Wallace Line

To grasp the full weight of this discovery, it helps to understand the formidable natural boundary that separates Sulawesi from mainland Asia: the Wallace Line. First drawn in the 19th century by British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, this invisible biological frontier cuts through the Indonesian archipelago and divides the ecozones of Asia and Australasia. West of the line, tigers and elephants roamed. East of it, marsupials and cassowaries ruled.

For animals—and early hominins—crossing the Wallace Line meant a daunting sea voyage, not a simple land migration. It has long stood as a barrier that early scientists believed only modern humans could have breached. But the tools unearthed at Calio, Sulawesi, tell a different story. They suggest that our extinct human relatives were capable of open-ocean travel much earlier than we had thought, and they reached the remote islands of Wallacea—previously considered out of reach—over a million years ago.

A Million-Year-Old Workshop by the River

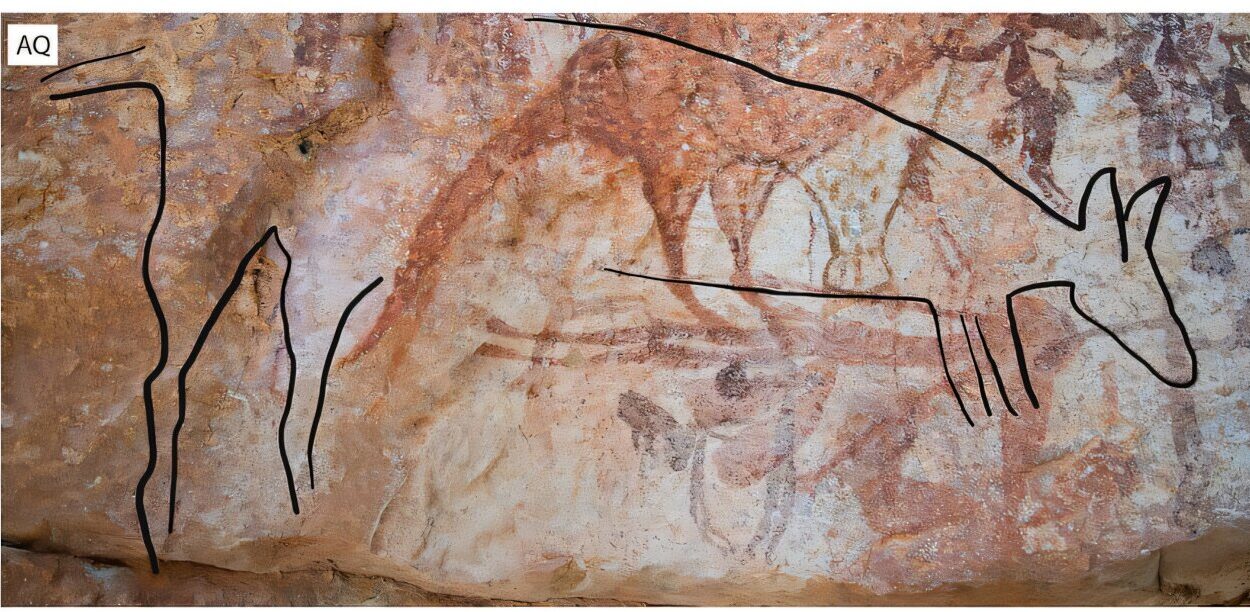

During the Early Pleistocene, the site where the Calio tools were found would have looked very different. It wasn’t farmland then; it was a lush riverside zone—rich with life, and apparently, a workshop for early tool-makers.

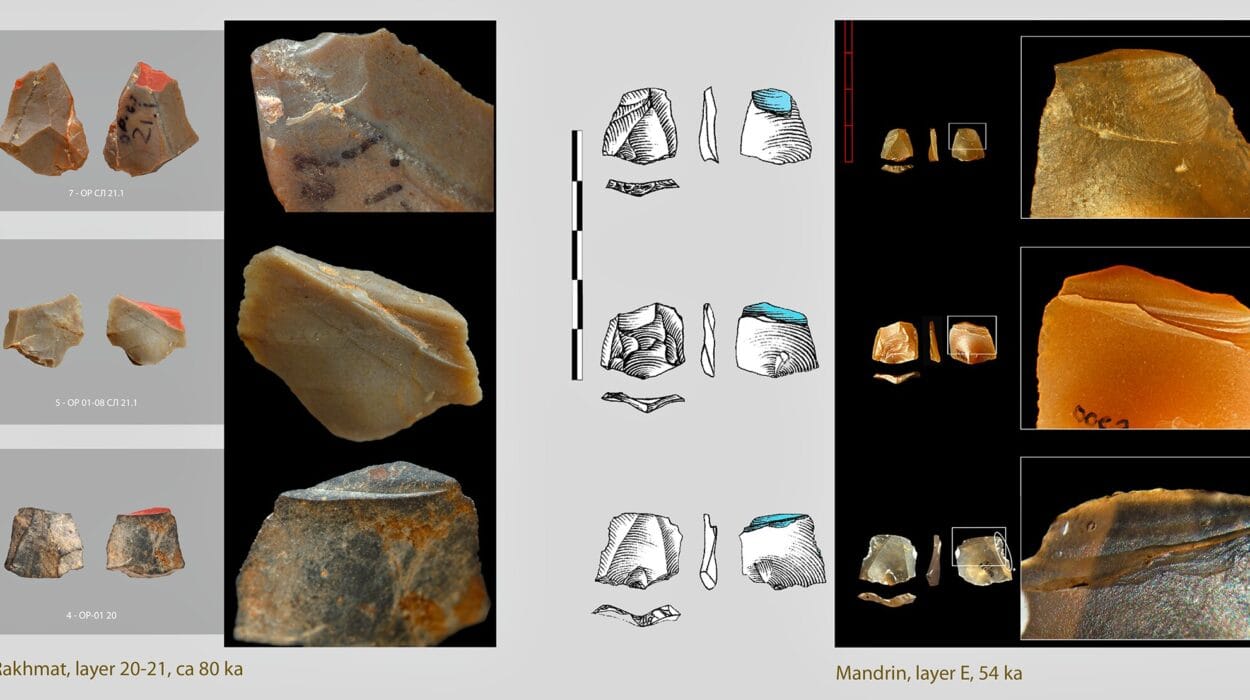

The artifacts themselves are small, sharp-edged stone flakes. These flakes were carefully struck from larger pebbles, likely scavenged from the surrounding riverbeds, by hominins using basic stone-knapping techniques. In other words, whoever lived here had the knowledge to make tools—perhaps to cut meat, scrape hides, or hunt smaller animals. These were no random rocks. They were the fingerprints of cognition, of hands shaping nature for survival.

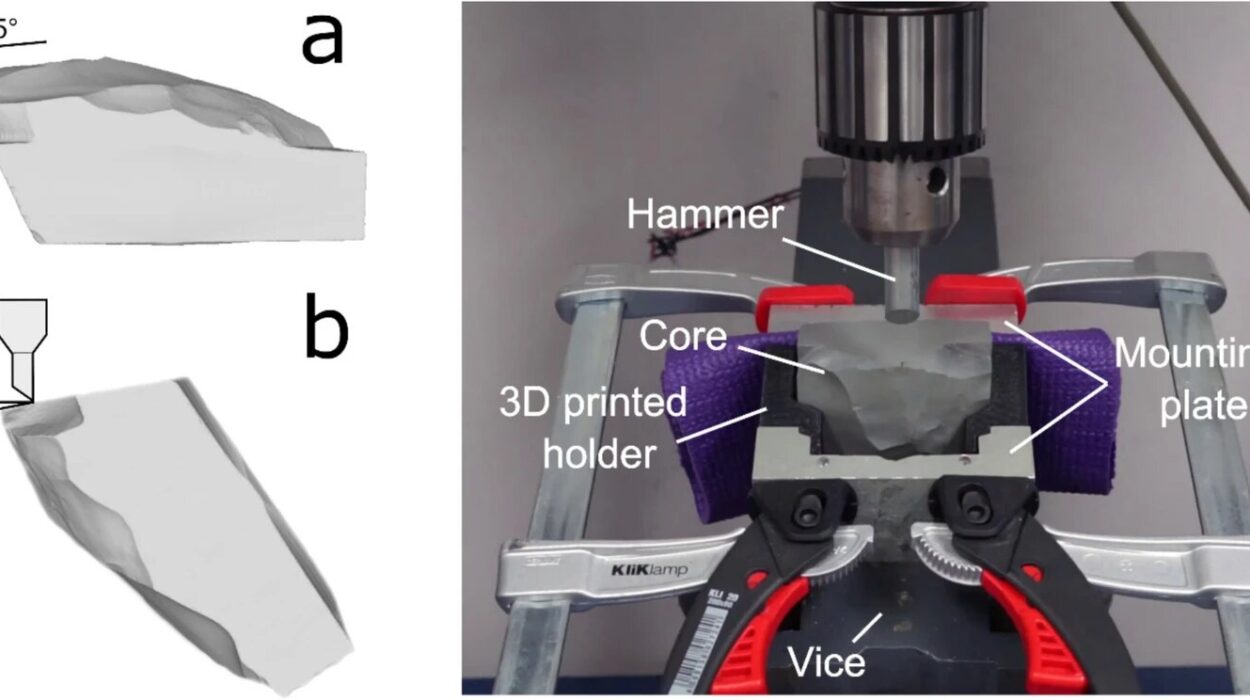

While only seven artifacts were found during the initial excavation, their presence, and the geological context in which they were found, speak volumes. Using paleomagnetic dating techniques on the sandstone layers—alongside the direct dating of a pig fossil found in the same sediment—the team confirmed that these tools are at least 1.04 million years old.

Who Were These Mysterious Toolmakers?

While the tools whisper of hands and minds long vanished, they do not reveal who made them. No hominin fossils have been discovered at the Calio site—yet. And so, a new mystery emerges in the wake of this extraordinary find.

The identity of these early explorers remains elusive. But clues lie in the broader record of Southeast Asia and Wallacea.

Previously, Professor Brumm and his colleagues uncovered tools on the nearby island of Flores, dating to 1.02 million years ago. It was on Flores that scientists discovered Homo floresiensis—the so-called “hobbit” species, with its diminutive frame and distinct features. The hobbit likely descended from an early population of Homo erectus—a widespread hominin species known for its upright posture, large brain, and adaptability.

Fossils from Luzon in the Philippines suggest yet another island population existed there 700,000 years ago, adding weight to the idea that multiple hominin species, perhaps all related to Homo erectus, had crossed the seas and settled in isolated archipelagos throughout Southeast Asia.

The First Mariners of Humanity

This brings us to a profound possibility: the hominins who left their mark at Calio may have been among the earliest seafarers in human history.

That idea would have been ridiculed just a few decades ago. The mainstream view was that only Homo sapiens, with their complex language, social systems, and advanced tools, were capable of building watercraft and navigating ocean crossings. Yet more and more evidence now points to a humbler but no less awe-inspiring truth: early humans—long before our species emerged—were building rafts, crossing oceans, and expanding the boundaries of their world.

The Calio site strengthens this view. To get to Sulawesi from mainland Asia, early hominins would have had to cross several deep-water straits, navigating unpredictable currents and relying on simple technology and extraordinary courage. They didn’t need compasses or sails—just the will to push into the unknown.

Sulawesi: The Evolutionary Wild Card

While Flores has long captured the spotlight for the discovery of Homo floresiensis and other ancient finds, Sulawesi may be an even more intriguing evolutionary laboratory.

At over 12 times the size of Flores, Sulawesi is ecologically diverse and geologically complex—almost a mini-continent in its own right. “Sulawesi is a wild card,” says Professor Brumm. “If hominins were cut off on this huge and ecologically rich island for a million years, would they have undergone the same evolutionary changes as the Flores hobbits? Or would something totally different have happened?”

That’s the tantalizing question. On Flores, the hobbits are thought to have evolved through island dwarfism—a process where large-bodied species become smaller over time due to limited resources and isolated conditions. But Sulawesi, with its mountains, forests, and river systems, might have supported a different trajectory. Did its early inhabitants stay large and robust like their Homo erectus ancestors? Did they evolve into a new species altogether?

Until fossils are found, we can’t know. But the archaeological clock is now ticking. With the Calio discovery pushing the timeline back further than ever before, the race is on to uncover more evidence—and perhaps even the bones—of these ancient island pioneers.

Rewriting the Human Story

The Calio tools are more than just flakes of stone. They are shards of a much larger narrative—one that challenges long-held assumptions about human evolution and migration.

This is not just a tale of where early humans lived, but how they thought, how they adapted, and how they dared. In reaching Sulawesi, these ancient tool-makers crossed not only a sea but an evolutionary threshold. They stepped beyond the perceived limits of their kind, guided by curiosity, necessity, or accident. Whatever the reason, the result was monumental.

The study, titled “Hominins on Sulawesi during the Early Pleistocene”, is yet another reminder that the human story is far older, deeper, and more complex than we imagined. Each new discovery pushes the boundaries of our understanding—and sometimes, those discoveries come not from glamorous digs or high-tech labs, but from simple artifacts found in the soil of a cornfield.

The Next Chapter Awaits Beneath the Soil

What lies buried beneath Sulawesi’s rugged landscape remains unknown. But this island, once believed to be unreachable to early humans, may hold the keys to an entire chapter of human evolution that has yet to be written.

The scientists are already preparing for future excavations. There is hope—strong hope—that the next dig might uncover hominin bones, a tooth, or even a skull. That would tell us not just that someone was here, but who they were, how they lived, and how they changed across a million years of isolation.

For now, the Calio tools stand as silent testimony to a great journey taken by our ancestors—a journey across seas, through time, and into mystery.

As Professor Brumm puts it, “It’s a significant piece of the puzzle… but the Calio site has yet to yield any hominin fossils; so while we now know there were tool-makers on Sulawesi a million years ago, their identity remains a mystery.”

Mystery, yes—but not forever. The stone speaks. We’re just beginning to listen.

More information: Hominins on Sulawesi during the Early Pleistocene, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09348-6 , www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09348-6