The Aztec Empire, which flourished in central Mexico between the 14th and early 16th centuries, was one of the most extraordinary civilizations of the pre-Columbian world. At the heart of its culture stood religion, a force so powerful that it shaped politics, war, agriculture, art, and daily life. The Aztecs did not see religion as something separate from existence—it was existence. To them, every sunrise, every harvest, every conquest, and every death carried spiritual meaning. The divine world and the human world were inseparably intertwined, like threads in an intricate tapestry woven by the gods themselves.

Among the countless deities venerated by the Aztecs, none loomed larger than the gods of war and agriculture. To the Aztec people, war and farming were not contradictory pursuits; rather, they were complementary forces. War provided the captives needed for sacrifice to nourish the gods, while agriculture ensured that the people themselves were nourished. Both domains—blood and maize, battle and harvest—were linked through cosmic necessity. Understanding the Aztec pantheon of war and agriculture is to glimpse the very soul of this civilization, and to see how they understood their role in maintaining the fragile balance of the universe.

The Aztec Worldview: Balance Between Life and Death

Before exploring the gods themselves, it is essential to understand the Aztec worldview. The Aztecs believed the universe was unstable, a fragile creation held together by divine effort. Life was not permanent or guaranteed; it required constant renewal through ritual, sacrifice, and devotion. The gods had created the world through great struggles, even self-sacrifice, and now it was humanity’s responsibility to repay that debt.

In this worldview, war and agriculture were not simply human activities but divine necessities. Crops could not grow without the gods’ blessing, and the gods would not continue their cosmic labors without offerings. Blood, seen as the essence of life, was the most precious gift to the divine. Maize, the sacred grain that sustained the Aztec people, was equally central to their survival. Together, blood and maize symbolized the reciprocal relationship between humans and gods, war and farming, life and death.

Huitzilopochtli: The Hummingbird of the South

At the heart of Aztec religion stood Huitzilopochtli, the god of the sun and war. His name means “Hummingbird of the South,” but he was no gentle creature. Huitzilopochtli embodied the relentless power of the sun, the warrior who battled each day against darkness to bring light to the world. The Aztecs believed that without his daily triumph, the universe would collapse into chaos.

Huitzilopochtli was also the divine patron of the Mexica people, guiding their migrations until they founded Tenochtitlan, the great capital of the Aztec Empire. In his honor, the Aztecs built the Templo Mayor, the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan, where sacrifices were performed to ensure his strength. War captives were offered to him so that his solar energy could continue burning.

For the Aztecs, every battle was fought not just for earthly territory but for cosmic survival. Warfare was “flower war”—a sacred duty to capture enemies alive, so their hearts could be given to Huitzilopochtli. Without war, the sun itself might falter, plunging the world into eternal night.

Tezcatlipoca: The Smoking Mirror of Conflict

Another powerful deity tied to war was Tezcatlipoca, whose name means “Smoking Mirror.” He was a complex god, embodying conflict, destiny, and the unpredictable forces of life. Unlike Huitzilopochtli, who represented solar order and victory, Tezcatlipoca was a god of chaos, temptation, and struggle.

Tezcatlipoca was often associated with sorcery and night skies. He could bring fortune or misfortune, empower kings or topple empires. Warriors prayed to him for strength, knowing that the outcome of battle was often unpredictable. In art, he was sometimes depicted with an obsidian mirror replacing one of his feet, symbolizing his ability to see into the hidden realms of fate.

Though feared, Tezcatlipoca was also revered. He reminded the Aztecs that war was not only about conquest but about cosmic testing. Every warrior’s life was at the mercy of divine will, and Tezcatlipoca embodied the harsh truth that human existence was fragile and uncertain.

Tlaloc: The Rain Bringer

If war sustained the sun, agriculture sustained the people. For this reason, Tlaloc, the god of rain and fertility, was one of the most beloved and feared deities in the Aztec pantheon. He was depicted with goggle-like eyes and fangs, a symbol of both the life-giving rains and the destructive storms he could unleash.

Tlaloc’s domain was essential for maize, beans, and squash—the sacred “Three Sisters” of Mesoamerican agriculture. Farmers prayed to him for favorable weather, offering sacrifices to ensure abundant harvests. But Tlaloc was a volatile god; if angered, he could withhold rain, sending devastating droughts, or drown fields with floods.

Children were often sacrificed to Tlaloc, as their tears were believed to bring rain. This practice, unsettling to modern sensibilities, reflected the Aztec belief that life and nourishment required sacred exchange. Without rain, the people would starve; without offerings, Tlaloc would withhold his blessings.

Centeotl: The God of Maize

Perhaps no deity was more closely tied to everyday Aztec life than Centeotl, the maize god. Maize was not simply food—it was life itself. The Aztecs believed humanity had been created from maize dough, shaped by the gods into the first people. To eat maize was to partake in one’s own origins.

Centeotl was depicted as a youthful figure, sometimes adorned with maize stalks. Festivals in his honor celebrated planting and harvest seasons. During these rituals, dancers and priests performed ceremonies to ensure the continued fertility of the soil and the protection of crops.

Through Centeotl, agriculture became sacred. To sow maize was to participate in a divine act of creation. Each kernel planted was a seed of life, mirroring the sacrifices of the gods who had given their blood to animate humanity.

The Templo Mayor: Axis of War and Agriculture

The heart of Aztec religious life was the Templo Mayor, the great double-pyramid in Tenochtitlan. Its twin temples were dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun, and Tlaloc, the god of rain and agriculture. This architectural pairing was no accident—it reflected the dual forces upon which the Aztec world depended.

The temple symbolized the unity of opposites: war and agriculture, fire and water, life and death. In the rituals performed there, the Aztecs enacted their cosmic role, ensuring both the nourishment of the gods and the fertility of the earth. The sacrifices on the temple’s steps were not merely acts of violence; they were offerings to keep the universe in balance.

The Templo Mayor was, in essence, a cosmic stage. Each ritual, each sacrifice, each prayer resonated with the belief that the fate of the universe hung in the balance of divine forces.

Rituals of Blood and Maize

Aztec rituals tied war and agriculture together in symbolic ways. Blood sacrifices to Huitzilopochtli ensured the sun’s journey, while offerings to Tlaloc and Centeotl ensured the growth of maize. Festivals often combined elements of both.

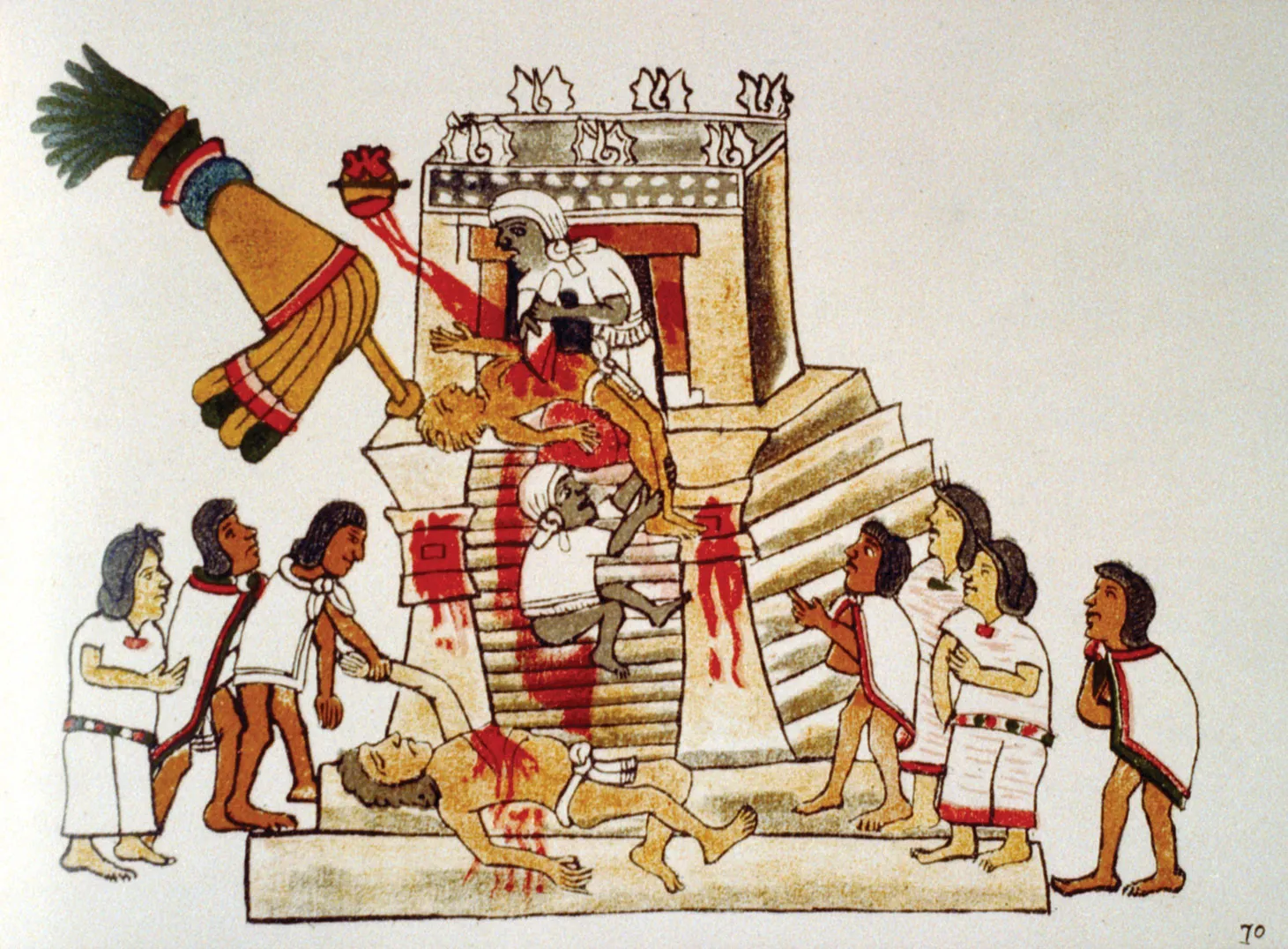

One notable example was the festival of Tlacaxipehualiztli, honoring Xipe Totec, the god of agricultural renewal and war. During this festival, warriors engaged in ritual combat, and captives were sacrificed. Priests wore the flayed skins of victims, symbolizing the shedding of old life and the rebirth of crops. This gruesome imagery mirrored the agricultural cycle: just as seeds must be buried and reborn, so too must human life be renewed through sacrifice.

Through such rituals, the Aztecs expressed their belief that war and agriculture were inseparable. The spilling of blood and the sowing of maize were both acts of cosmic nourishment.

The Ethical Dilemma of Sacrifice

From a modern perspective, the human sacrifices of Aztec religion are difficult to comprehend. Yet to the Aztecs, these acts were not cruelty for its own sake but the highest form of devotion. They believed the gods had sacrificed themselves to create the world, and it was humanity’s duty to reciprocate.

War provided the captives needed for sacrifice. Agriculture provided the sustenance of the people. Both were bound by the same principle: the cycle of giving and receiving. To the Aztecs, sacrifice was not an ending but a continuation of cosmic life.

While disturbing, this worldview reflected a profound spiritual logic. It was not indifference to human suffering but an urgent sense of cosmic responsibility. In their eyes, to withhold sacrifice was to invite universal collapse.

Conquest, Collapse, and the Fate of the Gods

When the Spanish arrived in the early 16th century, they encountered a world where gods of war and agriculture dominated every aspect of life. To the conquistadors, Aztec practices seemed barbaric, fueling the justification for conquest and conversion. The destruction of the Templo Mayor and the suppression of indigenous rituals marked the end of the Aztec religious order.

Yet the gods did not vanish. In hidden rituals, in folk traditions, and in the agricultural practices of rural Mexico, echoes of Aztec religion endured. Maize remains sacred in Mexican culture, and festivals still celebrate cycles of planting and harvest. The memory of Huitzilopochtli, Tlaloc, and Centeotl lingers in myth and history, reminding us of the enduring power of belief.

The Legacy of Aztec Religion

The Aztec religion of war and agriculture reveals a worldview both alien and familiar. Its practices may shock us, but its underlying truths—dependence on the sun, the rains, the soil, and the balance of life—remain as relevant as ever. In their devotion to sustaining the universe, the Aztecs remind us of humanity’s profound connection to nature and the cosmos.

Today, as we face global challenges of climate change, food security, and conflict, the Aztec vision of balance between war and agriculture, destruction and renewal, resonates with renewed urgency. Though their empire fell, their religion still speaks, offering lessons about the fragility of existence and the responsibility we bear toward life itself.

Conclusion: Gods of Blood and Maize

The Aztec gods of war and agriculture were not distant figures but living forces that shaped every heartbeat of their civilization. Huitzilopochtli’s demand for sacrifice fueled the empire’s military might, while Tlaloc and Centeotl embodied the agricultural lifeblood of the people. Together, they formed the twin pillars of Aztec existence, uniting battlefields and cornfields in a single cosmic order.

Aztec religion was a drama of survival, an eternal negotiation between humanity and the divine. In the gods of war and agriculture, we see a civilization striving to sustain the fragile flame of life, even at the cost of blood. Their story is both a testament to the power of belief and a reminder of the deep, often tragic, bond between human beings and the forces of nature.

The Aztecs believed that without war, the sun would falter, and without maize, humanity would perish. In their religion, war and agriculture were not opposites but inseparable halves of existence. And though their empire fell beneath foreign conquest, the echoes of their gods still whisper in the maize fields of Mexico and in the human struggle to live in harmony with the universe.