Long before the pyramids of Egypt reached their towering heights, before the ziggurats of Mesopotamia rose against the desert skies, there thrived a civilization whose echoes still whisper through the dust of the Punjab plains. That civilization was the Indus Valley Civilization, and one of its greatest cities was Harappa.

Today, Harappa lies in ruins—its once-proud walls reduced to scattered bricks, its streets silenced by millennia of abandonment. Yet, these broken remnants are more than just archaeological fragments; they are keys to a story that reshaped our understanding of early human history. Harappa is not simply a ruin but a window into one of humanity’s earliest urban experiments, a society that flourished around 2600 BCE and rivaled the mightiest civilizations of its age.

The rediscovery of Harappa in the 19th and 20th centuries shocked the world. For centuries, scholars had believed that ancient India’s history began with the Vedic Age. But here, buried beneath centuries of soil and neglect, was proof of an advanced urban culture predating the Vedas by more than a thousand years. Harappa transformed history, showing that South Asia was not merely a passive recipient of civilization but a cradle of urbanism in its own right.

The Setting of Harappa

Harappa is located in present-day Punjab, Pakistan, nestled along the once-mighty Ravi River, a tributary of the Indus. In its prime, the city thrived on fertile floodplains, where agriculture flourished. The river provided not only water but also a vital artery for transport and trade, connecting Harappa with other settlements of the Indus Valley Civilization.

The geography of Harappa was a gift and a challenge. The fertile plains allowed intensive farming of wheat, barley, sesame, and cotton—the latter making the Harappans among the first people in the world to cultivate and spin cotton. The rivers, however, were unpredictable, flooding heavily at times and shifting course over centuries. This duality of abundance and uncertainty shaped Harappan society, pressing its people to build with resilience and foresight.

The Discovery of Harappa

For centuries, Harappa lay forgotten beneath mounds of earth. Local villagers occasionally stumbled upon baked bricks, carting them away for use in modern construction. It was not until the mid-19th century that Harappa’s significance came to light.

In 1826, Charles Masson, a British deserter turned explorer, noted the presence of large ruins near Harappa, but his observations attracted little scholarly attention. It was in 1856, when workers building a railway between Lahore and Multan unearthed large quantities of fired bricks, that Harappa’s remains were first stripped away in earnest—ironically, many of the bricks from the ancient city ended up as ballast for the railway.

It wasn’t until the 1920s, under the supervision of archaeologists such as Sir John Marshall, Daya Ram Sahni, and R. D. Banerji, that Harappa and Mohenjo-daro were recognized as part of a vast, previously unknown civilization. What emerged from the dust was astonishing: a civilization that rivaled Mesopotamia and Egypt in scale, complexity, and innovation.

The Urban Splendor of Harappa

What struck archaeologists most about Harappa was its sophisticated urban planning. This was not a haphazard settlement but a carefully designed city, built according to a grid system that revealed foresight and civic organization.

The city was divided into two main sections: the “citadel” and the “lower town.” The citadel, raised on a massive mud-brick platform, contained monumental structures, possibly used for administrative or ceremonial purposes. The lower town housed the majority of the population, with carefully laid-out residential quarters, workshops, and marketplaces.

Harappa’s streets were wide and straight, intersecting at right angles in a grid pattern that modern urban planners still admire. Houses were built of uniform baked bricks, often with multiple rooms and courtyards. Many homes had private wells and bathrooms, connected to an elaborate drainage system that channeled wastewater into covered sewers along the streets. This attention to public hygiene was unparalleled in the ancient world and would not be matched in many parts of the world for thousands of years.

Harappa was, in every sense, a city ahead of its time—a testament to the organizational genius of its builders.

The Society and Daily Life of Harappans

Harappa was not only a city of bricks and drains; it was a city of people. Its inhabitants, estimated in the tens of thousands, lived lives that combined agriculture, trade, craftsmanship, and domestic life.

The Harappans were primarily agriculturalists. Fields around the city produced wheat, barley, peas, mustard, and cotton. They domesticated cattle, buffalo, goats, and sheep, while evidence suggests they may have used camels and elephants as well. Fishing supplemented their diet, with nets and hooks discovered among the artifacts.

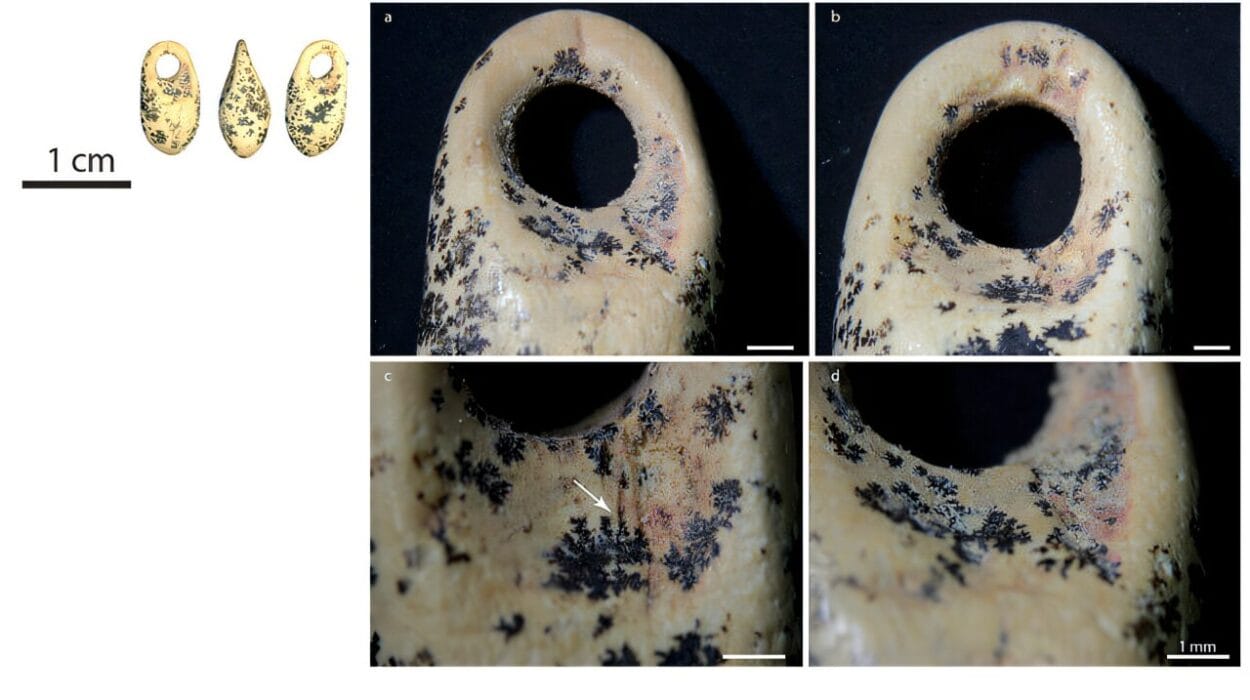

Crafts flourished in Harappa. Skilled artisans produced exquisite beads, pottery, seals, figurines, and tools. Bead-making, in particular, was highly advanced, with craftsmen drilling tiny holes in semi-precious stones such as carnelian. The presence of standardized weights and measures indicates a regulated system of trade and economic exchange.

Social hierarchy in Harappa is more difficult to discern. Unlike Egypt or Mesopotamia, there is little evidence of grand palaces, lavish tombs, or statues of rulers. This absence suggests that Harappan society may have been more egalitarian, or at least less focused on displays of centralized power. Instead, authority may have rested in councils or institutions rather than in a single monarch.

Religion, too, remains elusive. Numerous terracotta figurines, often interpreted as fertility goddesses, have been found, along with seals depicting animals and horned figures reminiscent of later Hindu deities like Shiva. Ritual bathing areas suggest the importance of water in Harappan spiritual life, foreshadowing the central role of purification in later South Asian religions.

The Indus Script: An Unsolved Mystery

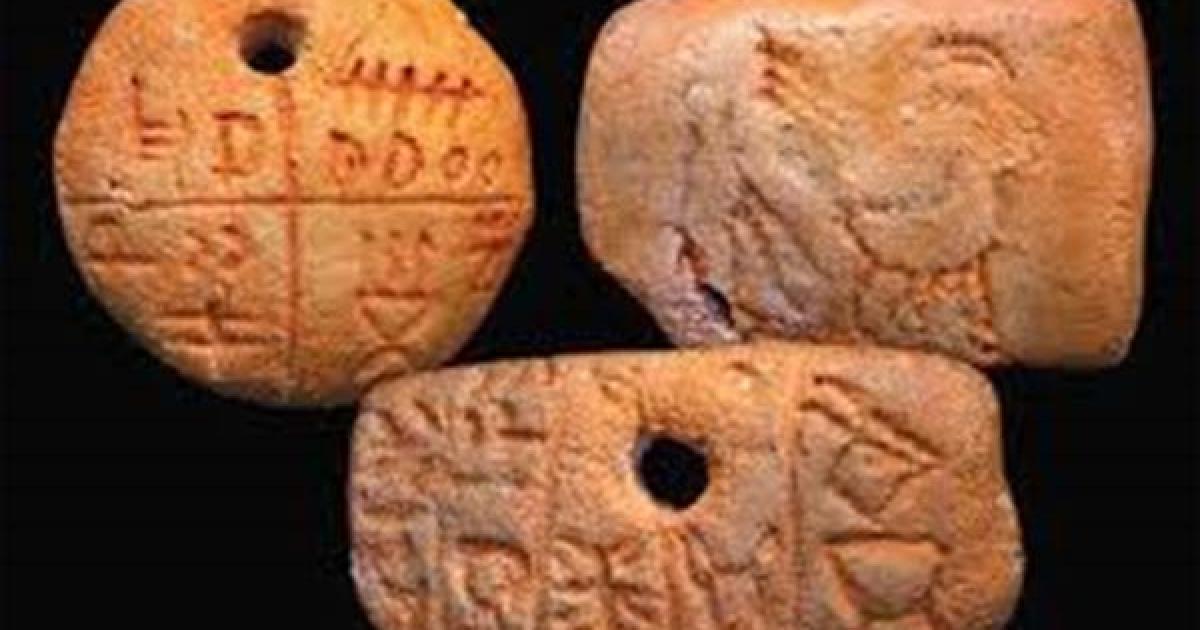

Among the most tantalizing aspects of Harappa is its script. Thousands of seals, tablets, and pottery fragments bear inscriptions in a writing system that remains undeciphered to this day.

The Indus script consists of short sequences of symbols, often accompanied by animal motifs such as bulls, elephants, and unicorn-like creatures. While many scholars believe it represents a full-fledged writing system, others argue it may have been a proto-writing used for administrative or symbolic purposes.

Despite decades of effort, the script has resisted all attempts at translation. Without bilingual inscriptions (like the Rosetta Stone for Egyptian hieroglyphs), the language of the Harappans remains locked away. Until it is deciphered, our understanding of their politics, religion, and culture will remain incomplete.

Yet this very mystery is part of Harappa’s allure—a reminder that ancient civilizations still hold secrets beyond our grasp.

Trade and Connectivity

Harappa was not an isolated city but part of a vast economic network. Archaeological evidence reveals extensive trade within the Indus region and beyond.

Indus seals have been found in Mesopotamia, suggesting contact between Harappa and cities like Ur and Sumer. Harappan carnelian beads and cotton textiles likely traveled westward, while silver, tin, and wool may have been imported in return. Trade routes extended eastward into Gujarat and southward into peninsular India, bringing resources such as lapis lazuli, shells, and semi-precious stones.

The standardized weights and measures found at Harappa indicate a regulated system of commerce, ensuring fairness in trade. This level of organization speaks to the sophistication of Harappan society, capable of sustaining long-distance economic relationships across challenging terrains.

Decline and Disappearance

Perhaps the greatest mystery of Harappa is its decline. By around 1900 BCE, the city and other Indus settlements began to wither. Streets fell silent, drains clogged, and the orderly life of the city crumbled. What caused this collapse?

Scholars propose several theories. Climate change may have played a role, as evidence suggests the Indus region experienced shifting river patterns and prolonged droughts around this time. Floods may have devastated agriculture, while the drying up of rivers cut off vital water supplies.

Another possibility is overexploitation of resources—deforestation, soil depletion, and ecological stress undermining the sustainability of Harappan society. Some scholars point to invasions by Indo-Aryan tribes, though archaeological evidence for violent conquest is scarce.

Most likely, the decline was not caused by a single event but a combination of environmental, social, and economic factors. By 1300 BCE, the great cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro were abandoned, their people dispersing into smaller rural communities.

Yet the legacy of Harappa did not vanish. Elements of Harappan culture—such as urban planning, craft traditions, and perhaps even religious practices—echoed into later South Asian civilizations, shaping the cultural fabric of the subcontinent.

Harappa and the Legacy of the Indus Civilization

Harappa is more than just ruins; it is a symbol of human ingenuity. It reminds us that 4,000 years ago, people on the Indian subcontinent built cities as advanced as any in the world. It challenges simplistic narratives of “civilization” arising only in Mesopotamia or Egypt and asserts South Asia’s role as a birthplace of urban complexity.

The legacy of Harappa lives on not only in archaeology but also in culture. Practices like ritual bathing, reverence for fertility, and symbolic animal motifs may trace their roots back to the Indus. Even the linguistic and cultural diversity of South Asia may carry echoes of Harappan heritage.

Harappa also forces us to confront the fragility of civilizations. Despite its achievements, the city collapsed under pressures of climate, environment, and societal strain. Its story resonates today, as modern societies face challenges of climate change, urban sustainability, and ecological balance.

Harappa in Modern Times

Today, Harappa is a major archaeological site, with excavations continuing to reveal new insights. Museums house artifacts that testify to the artistry and ingenuity of its people. Yet challenges remain: preservation of the ruins is difficult, threatened by urban encroachment, pollution, and limited resources.

For the people of South Asia, Harappa is not just an archaeological site but part of a shared heritage, a reminder that their ancestors built one of the world’s first great civilizations. It is a source of pride and identity, as well as a subject of continued fascination for scholars and laypeople alike.

Conclusion: Lessons from Harappa

Harappa stands as a testament to human creativity, resilience, and ambition. Its streets, drains, seals, and bricks tell the story of a civilization that valued order, cleanliness, trade, and community. Its mysteries—the undeciphered script, the uncertain religion, the enigmatic decline—remind us that history is never fully known, always inviting deeper inquiry.

In the silence of Harappa’s ruins, we hear echoes of both triumph and fragility. We are reminded that civilizations, no matter how advanced, are not eternal. They depend on balance—with nature, with society, with themselves.

To walk through Harappa today is to step into humanity’s shared past, to see how far we have come, and to reflect on where we are going. It is a city lost to time but alive in memory, a chapter in the epic of civilization that continues to inspire wonder and humility.