In the grand sweep of the universe, galaxies usually make themselves known. They blaze with the light of billions of stars, glowing across unimaginable distances. They announce their presence boldly, painting the cosmos with spirals, clusters, and halos. But not all galaxies want to be seen.

Some remain almost invisible—dim, ghostly structures known as low-surface-brightness galaxies. These galaxies are so faint that they seem to dissolve into the darkness around them. They contain only a sparse scattering of weak stars and are overwhelmingly dominated by dark matter, the mysterious substance that does not reflect, emit, or absorb light.

One of these elusive cosmic phantoms, called CDG-2, may be among the most heavily dark matter-dominated galaxies ever found. Its story, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, reads less like a routine discovery and more like a quiet triumph over cosmic invisibility.

Hunting What Cannot Be Seen

Finding a galaxy that barely glows is a bit like trying to spot a shadow in the middle of the night. Traditional methods struggle. After all, telescopes detect light—and CDG-2 offers almost none.

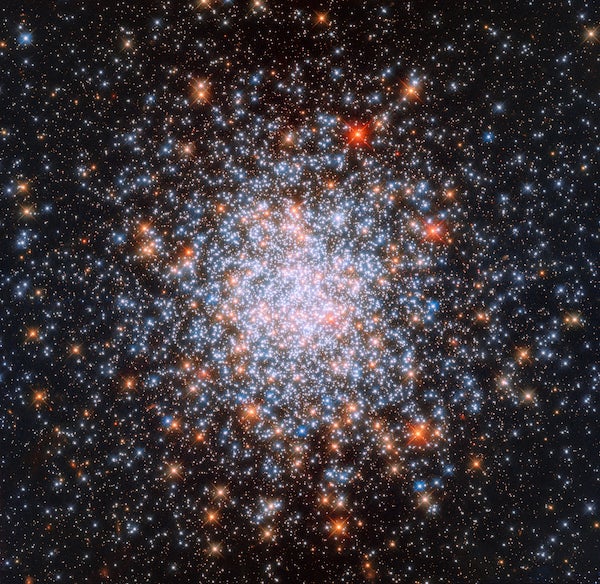

Instead of searching directly for faint stars, David Li of the University of Toronto and his team tried something clever. They searched for tight gatherings of globular clusters—compact, spherical groups of stars that typically orbit galaxies. Globular clusters are ancient, dense, and resilient. Even when the rest of a galaxy fades into near invisibility, these clusters can remain.

The team used advanced statistical techniques to comb through astronomical data, not looking for glowing galaxies, but for these small, bright knots of stars. Where several globular clusters appeared unusually close together, there might be something more lurking in the dark.

Their approach paid off. They identified ten previously confirmed low-surface-brightness galaxies and two additional dark galaxy candidates. Among them was CDG-2, hiding quietly in the shadows.

Four Clusters in the Dark

To confirm whether CDG-2 was truly a galaxy—and not just a coincidence of star clusters—astronomers turned to a trio of powerful observatories. They combined the sharp vision of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the wide-field capabilities of the European Space Agency’s Euclid space observatory, and the ground-based strength of the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii.

The first crucial clue came from Hubble. Its high-resolution images revealed a close grouping of four globular clusters inside the Perseus galaxy cluster, located about 300 million light-years away. Four clusters, tightly packed together in a place where they shouldn’t simply be floating alone.

But clusters by themselves are not a galaxy. The team needed more.

Follow-up observations using data from Hubble, Euclid, and Subaru revealed something extraordinary—a faint, diffuse glow surrounding the clusters. It was barely perceptible, like a smudge against the cosmic backdrop. Yet it was unmistakable evidence of an underlying galaxy.

“This is the first galaxy detected solely through its globular cluster population,” Li explained. In other words, CDG-2 was discovered not because its stars shone brightly, but because its clusters betrayed its presence.

Under conservative assumptions, the four clusters may represent the entire globular cluster population of CDG-2. If so, this galaxy is astonishingly sparse.

A Galaxy Made Mostly of Darkness

When astronomers began estimating CDG-2’s properties, the numbers told a startling story.

The galaxy’s total luminosity is equivalent to roughly 6 million sun-like stars. That may sound impressive, but compared to brighter galaxies, it is faint beyond belief. Even more remarkable is that the four globular clusters account for 16% of its visible content. In other words, a significant fraction of what little light CDG-2 emits comes from just these dense star clusters.

But the most astonishing number is this: approximately 99% of CDG-2’s mass appears to be dark matter.

Dark matter, by definition, cannot be seen. It does not glow. It does not reflect light. Yet its gravitational pull shapes galaxies and binds them together. In CDG-2, it seems to dominate almost entirely. The visible stars and star clusters are merely a thin scattering atop an immense invisible structure.

This makes CDG-2 one of the most dark matter-dominated galaxies ever identified.

Stripped of Its Birthright

How does a galaxy become so ghostly?

The answer likely lies in its environment. CDG-2 resides within the Perseus cluster, a dense region packed with galaxies. In such crowded neighborhoods, gravitational interactions can be violent and transformative.

The researchers suggest that much of CDG-2’s normal matter—the hydrogen gas needed to form new stars—was stripped away through gravitational interactions with neighboring galaxies. Without this gas, star formation would grind to a halt.

What remains is a skeleton of a galaxy: a massive halo of dark matter holding onto just a handful of stars and clusters. The globular clusters survived because of their immense stellar density and tight gravitational binding. They are compact and resilient, making them more resistant to gravitational tidal disruption. In a sense, they endured while the rest of the galaxy faded.

These clusters became cosmic signposts, marking the location of a galaxy that would otherwise have been almost impossible to detect.

A New Way to See the Unseen

The discovery of CDG-2 represents more than just the identification of a single faint galaxy. It demonstrates a powerful new method of finding the nearly invisible.

Instead of relying on brightness, astronomers can use globular clusters as tracers. Where clusters gather unusually close together, they may signal the hidden presence of a dark galaxy. Statistical techniques and machine learning can sift through enormous datasets to spot these subtle patterns.

As sky surveys grow ever larger, this approach will become increasingly important. Missions such as Euclid, NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory are generating vast amounts of data. Within these oceans of information may lie countless faint galaxies like CDG-2.

Finding them will require clever algorithms and persistence—but CDG-2 proves it can be done.

Why This Discovery Matters

At first glance, CDG-2 might seem unremarkable. It is faint, sparse, and almost empty. But in its very emptiness lies its importance.

Because CDG-2 is composed of about 99% dark matter, it offers a rare opportunity to study dark matter in a setting where ordinary matter plays only a minor role. In brighter galaxies, visible stars and gas complicate the picture. Here, the invisible dominates almost entirely.

CDG-2 also challenges our understanding of how galaxies evolve in dense environments. Its stripped state suggests that interactions within galaxy clusters can profoundly reshape smaller systems, removing the very material needed for future star formation.

Most importantly, this discovery shows that the universe still holds secrets hiding in plain sight. Entire galaxies can remain nearly undetected—not because they are rare, but because they barely shine.

By learning to look for the subtle clues—tight gatherings of globular clusters, faint glows against the darkness—astronomers are opening a new window into the shadowed side of the cosmos.

CDG-2 is not just a faint smudge 300 million light-years away. It is proof that even in the vast brightness of the universe, some of the most important discoveries are waiting quietly in the dark.

Study Details

Dayi (David) 大一 Li 李 et al, Candidate Dark Galaxy-2: Validation and Analysis of an Almost Dark Galaxy in the Perseus Cluster, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/adddab