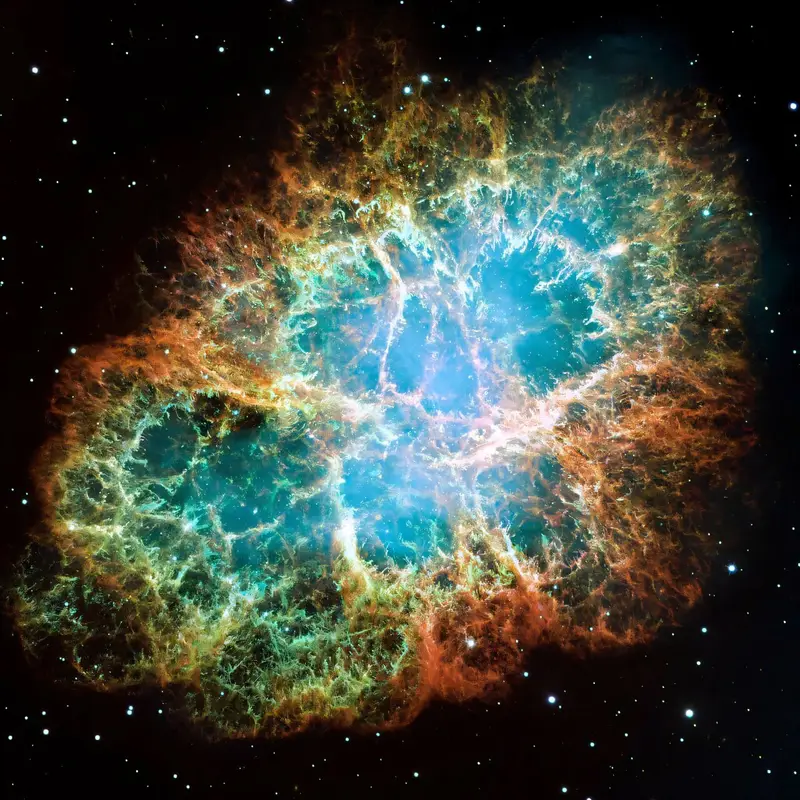

Most stars that end their lives in explosions do so with overwhelming finality. They tear themselves apart, scattering their remains into space in thick, tangled clouds that astronomers often compare to cauliflowers. These supernova remnants are chaotic, billowing, and unmistakable. Yet one object in the sky has long defied that familiar image. Known as Pa 30, this remnant looks less like cosmic debris and more like a frozen firework, with long, straight filaments shooting outward from a single point as if time itself paused in the middle of a brilliant burst.

For years, this strange appearance troubled astronomers. Pa 30 seemed to match the location of a mysterious “guest star” recorded by Chinese and Japanese observers in the year 1181, yet its structure made little sense. How could a supernova linked to a historical observation look so unlike every other stellar corpse? The answer, proposed by Eric Coughlin at Syracuse University, suggests that the star at the heart of Pa 30 did not quite manage to die in the way stars are expected to. It tried to explode, faltered mid-act, and in that failure created something entirely different.

The Explosion That Never Fully Happened

To understand Pa 30, one must first understand what normally happens when a white dwarf explodes. In a typical Type Ia supernova, nuclear burning races through the star and transitions into a supersonic detonation. The result is complete destruction. The white dwarf is obliterated, leaving nothing behind but an expanding shell of debris. These events are so thorough that no central star survives to tell the tale.

Pa 30 tells a different story. In this case, the nuclear burning near the white dwarf’s surface never made that crucial leap into a full detonation. The explosion began but fizzled before it could finish the job. Rather than blowing itself apart, the star endured. At the center of Pa 30 sits a hyper-massive white dwarf, scarred by a failed explosion but still intact.

This incomplete destruction places Pa 30 in a distinct category known as Type Iax supernovae. These events are rare, but astronomers are increasingly recognizing them as a genuine subclass rather than odd mistakes. They represent stars that attempt to explode and only partially succeed, leaving behind survivors where none were expected.

A Survivor That Would Not Stay Quiet

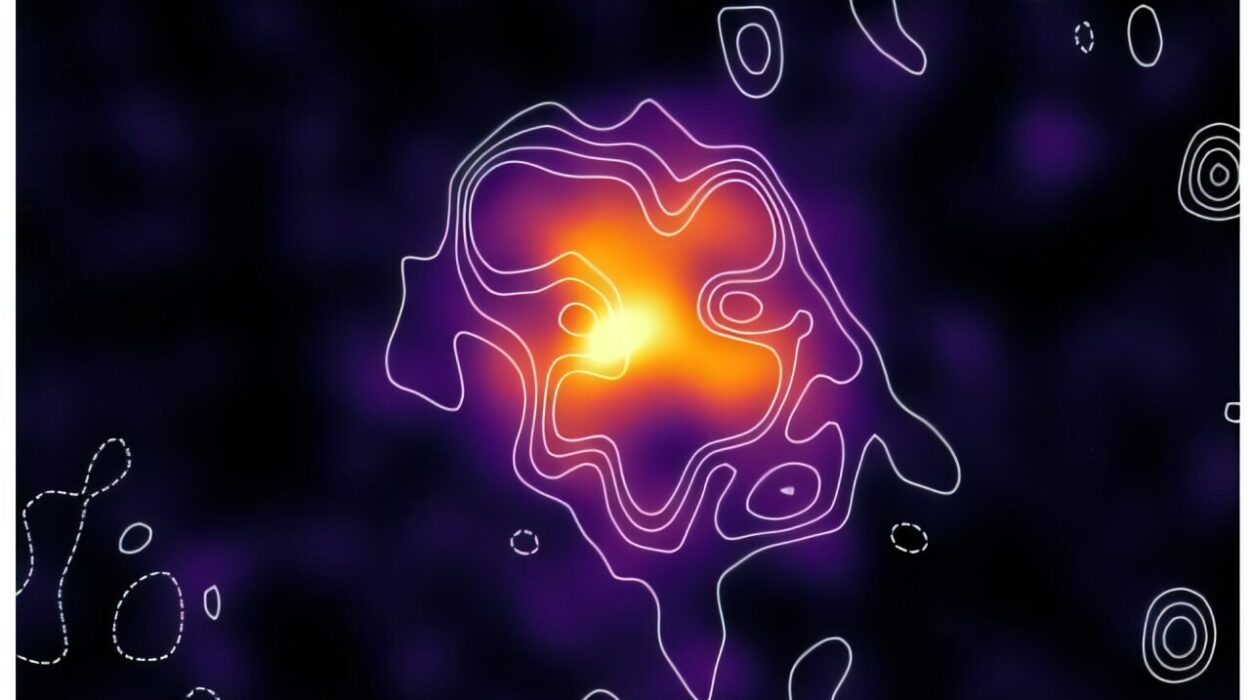

Survival did not mean serenity. The white dwarf left behind by Pa 30 did not settle into silence after its failed death. Instead, it unleashed an extraordinarily fast wind, racing outward at roughly 15,000 kilometers per second. This wind was no ordinary stellar breeze. It was dense and enriched with heavy elements forged during the brief, incomplete burst of nuclear burning.

As this powerful wind surged into space, it slammed into the surrounding gas. The encounter created a sharp boundary between two very different materials: the heavy, fast-moving wind and the lighter gas already occupying the region. At this interface, the conditions were primed for a fundamental piece of physics to take over, one that governs how fluids behave when density and motion clash.

Fingers Born From Instability

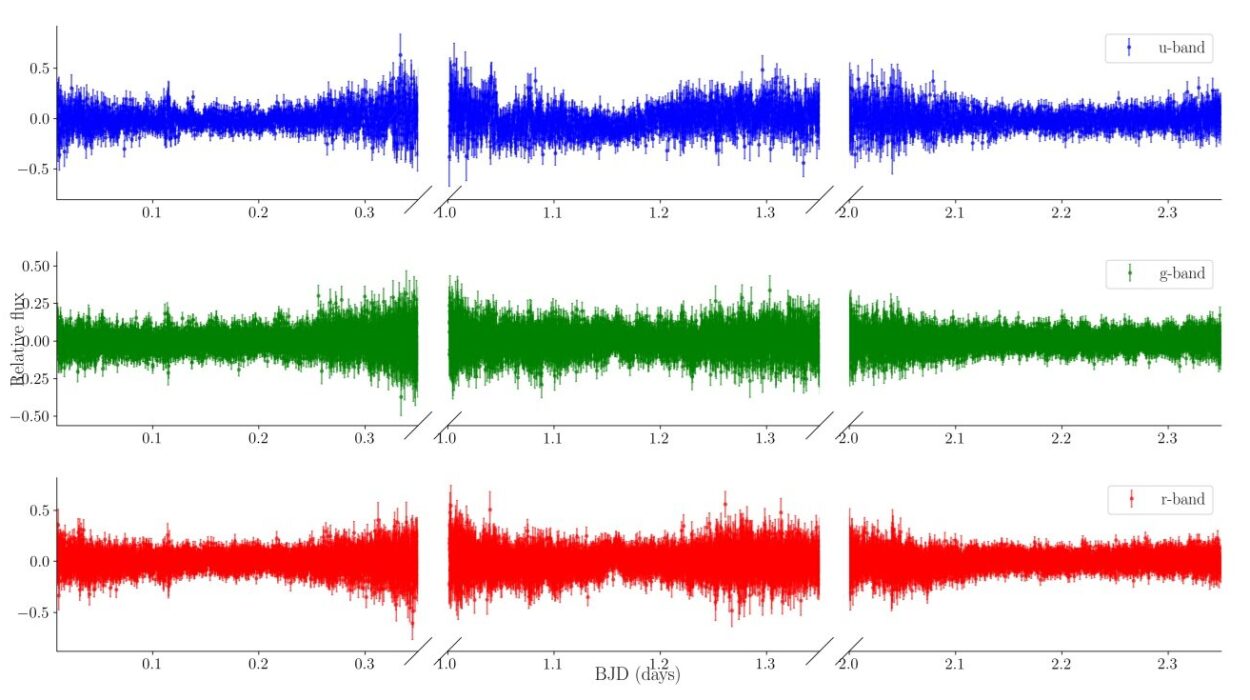

The physics responsible for Pa 30’s strange beauty is known as the Rayleigh–Taylor instability. It occurs whenever a heavier fluid pushes into a lighter one. The result is not a smooth boundary, but the growth of finger-like plumes that penetrate forward. On Earth, this instability produces the familiar mushroom shapes seen in explosions, including the rising columns of nuclear tests. In space, it can sculpt gas and plasma into intricate forms.

In Pa 30, these plumes became the long, straight filaments that radiate from the remnant’s center. They appear like frozen trails from a sparkler, each one tracing the path of heavy material punching outward into lighter surroundings. This alone, however, does not explain why Pa 30 looks so clean and ordered. In most supernova remnants, these initial fingers do not remain intact.

Why Chaos Never Took Over

Ordinarily, another process follows close behind the Rayleigh–Taylor instability. This second instability causes the fingers to curl, twist, and tear apart, mixing the material into chaotic wisps. It is the reason most supernova remnants lose any early symmetry and devolve into turbulent clouds. Smoke curls, shreds, and blends because of this mixing, and stellar debris behaves much the same way.

Pa 30 escaped this fate for a simple but powerful reason. The wind launched by the surviving white dwarf was far denser than the surrounding gas. The contrast was so extreme that the second instability never gained a foothold. Without it, the fingers were never shredded. Instead, they continued to stretch outward, continuously fed by the dense wind from the center. Over time, this process preserved the long filaments, locking in the firework-like appearance that makes Pa 30 so unusual.

Simulations, History, and a Nuclear Echo

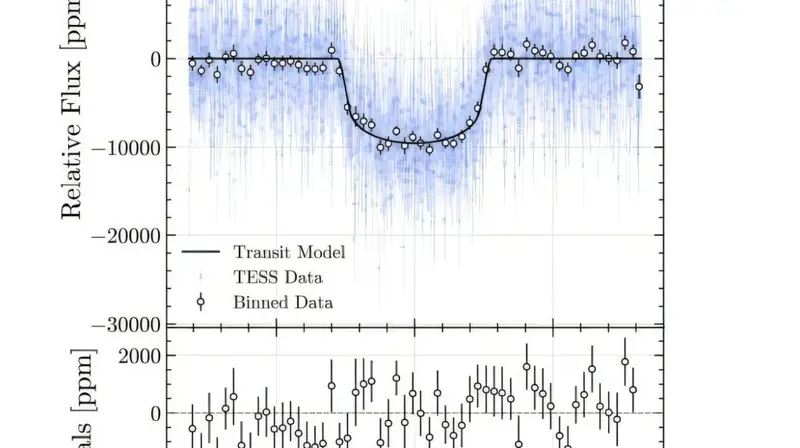

Coughlin’s work does not rely on imagination alone. His paper includes simulations showing that high density contrasts naturally produce exactly the kind of structures seen in Pa 30. When the heavy material remains dominant, filaments grow and persist rather than dissolving into chaos.

Intriguingly, the research draws an unexpected parallel with declassified photographs from the 1962 Kingfish nuclear test. In the earliest moments after detonation, similar filamentary patterns appear, briefly tracing straight fingers before evolving into cauliflower-like shapes. The key difference lies in timing and feeding. In the nuclear test, the structures quickly give way to turbulence. In Pa 30, the dense wind kept nourishing the filaments, allowing them to grow rather than collapse into disorder.

This comparison underscores how universal the underlying physics can be. Whether in Earth’s atmosphere or deep space, the same rules govern how matter behaves under extreme conditions. Pa 30 is a cosmic-scale demonstration of principles that can also be glimpsed in human history.

A Broader Family of Failed Deaths

Type Iax supernovae like Pa 30 are no longer viewed as mere curiosities. They represent a meaningful outcome of stellar evolution, one where explosions stall rather than complete. Coughlin suspects that Pa 30 may not be unique. Similar filamentary structures could appear in other astrophysical settings where dense winds collide with lighter material.

One such possibility includes tidal disruption events, where black holes tear stars apart. In these environments, powerful outflows and sharp density contrasts may again set the stage for long-lived filaments. Pa 30 thus becomes not just a single explanation for a historical remnant, but a template for understanding structure formation in extreme cosmic events.

A Guest Star Reconsidered

Pa 30 occupies a rare position in astronomy. It is one of the few deep-space events where modern modeling can be directly tied to historical observations. The “guest star” of 1181, once a fleeting note in ancient records, has become a detailed case study in stellar behavior. What was once simply an unexplained bright point in the sky is now understood as the visible trace of a star that failed to fully destroy itself.

This connection bridges centuries of human curiosity. Observers long ago saw something new appear in the heavens, unaware of the complex physics unfolding. Today, scientists can reconstruct that moment, revealing not just an explosion, but an incomplete one that left behind both a survivor and an enduring signature.

Why This Strange Remnant Matters

Pa 30 matters because it expands the story of how stars die. It shows that stellar death is not always absolute, and that failure can be just as informative as success. By explaining Pa 30’s distinctive filaments, researchers have illuminated a pathway between explosion and survival, one governed by density, motion, and instability rather than simple destruction.

This work also demonstrates the power of combining observation, simulation, and historical context. A puzzling shape in the sky, ancient records of a “guest star,” modern computational models, and even analogies to nuclear tests all converge to tell a coherent story. Pa 30 reminds us that the universe does not always conform to our neat categories. Sometimes, a star dies with a complicated whimper instead of a clean bang, leaving behind unexpected beauty and a deeper understanding of the forces that shape the cosmos.