Flowering plants are everywhere. They lace forests with color, fill fields with grain, and quietly support almost every terrestrial ecosystem. Yet beneath their familiar beauty lies a mystery that has unsettled plant biologists for decades: how did angiosperms, the flowering plants, acquire such extraordinary diversity? For many researchers, the answer seemed to lie deep in their genomes, in ancient moments when entire sets of genes were duplicated at once. These events, known as whole-genome duplications, have long been suspected as powerful engines of evolutionary innovation. But proving that they happened, especially in the distant past, has turned out to be far more difficult than anyone expected.

The challenge is not simply technical. It is philosophical as well, because ancient genomes do not preserve their history neatly. Over time, duplicated genes are lost, chromosomes rearrange themselves, and molecular signals blur. What remains is often a faint echo rather than a clear record. For years, scientists have debated whether flowering plants experienced one ancestral whole-genome duplication or two. A new study now steps into this long-standing debate with a fresh perspective, using an unexpected set of genetic clues to tell a clearer story.

The Rise of a Controversy Written in Duplicates

The idea that whole-genome duplication has shaped the evolution of seed plants is not controversial. Polyploidization is widely recognized as a key driver of both the origin of seed plants and the evolution of their traits. What has remained contentious is how many such events occurred early in plant history and exactly where they fall on the evolutionary timeline.

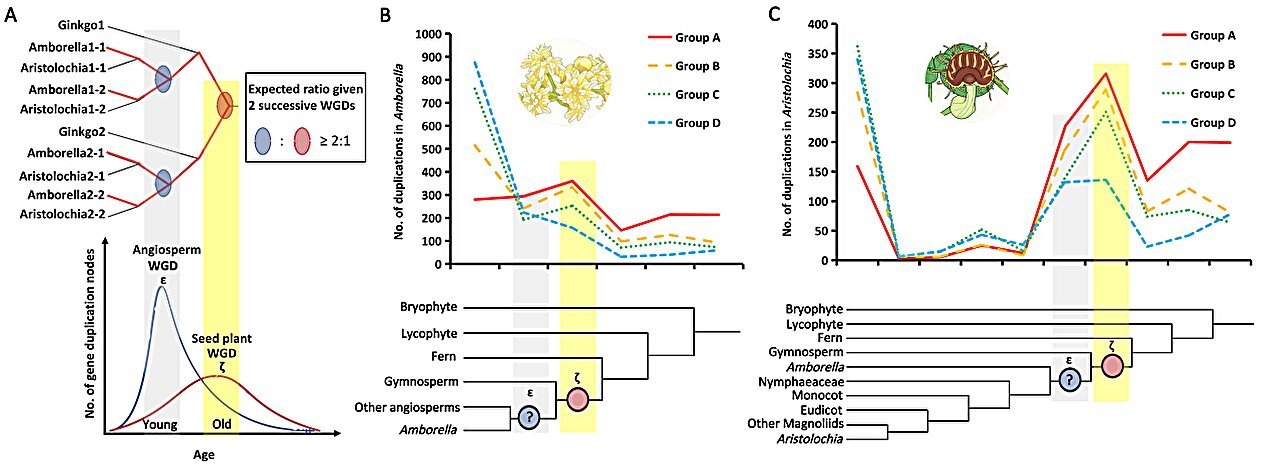

In 2011, researchers analyzing the ages of duplicated genes noticed a striking pattern. The data showed a bimodal distribution of gene duplications that appeared to predate the split between monocots and eudicots, the two great branches of flowering plants. From this pattern emerged a bold proposal: there were two independent ancestral whole-genome duplication events. One, called the ζ event, occurred in the common ancestor of all seed plants. The other, named the ε event, was thought to have occurred later, specifically in the ancestor of angiosperms.

This interpretation offered an elegant explanation for the success of flowering plants. A second round of genome duplication, layered atop an earlier one, could have provided raw genetic material for innovation, flexibility, and diversity. For a time, the idea gained traction. But science rarely moves in straight lines.

In 2017, another study cast doubt on this picture. It argued that the apparent bimodal signal might not reflect genuine evolutionary events at all. Instead, it suggested that methodological artifacts were at work, particularly inconsistencies in how phylogenetic nodes were calibrated for molecular dating. If the clock itself was misaligned, the echoes of duplication might be distorted. With that critique, the field reached an uneasy stalemate. The question of whether angiosperms experienced their own ancestral whole-genome duplication remained unresolved.

Listening to Genes That Cannot Be Ignored

The new study approaches this impasse by asking a different kind of question. Instead of treating all duplicated genes as equal witnesses to ancient events, the researchers focused on a special class known as dosage-sensitive genes. These genes encode core components of protein complexes, signaling pathways, or regulatory networks. Their defining feature is fragility. Altering their dosage, increasing or decreasing the number of copies, can disrupt the delicate stoichiometric balance inside a cell.

Because of this sensitivity, dosage-sensitive genes behave differently after a whole-genome duplication. When an entire genome is duplicated, these genes are often retained rather than lost, precisely because losing one copy would unbalance the system. Over evolutionary time, this makes them unusually reliable markers of ancient duplication events. Where other genes may vanish or rearrange beyond recognition, dosage-sensitive genes tend to hold on.

Researchers from the Wuhan Botanical Garden of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Ghent University recognized the potential of these genes as evolutionary signposts. By following their retention patterns, the team hoped to cut through the noise that had obscured earlier analyses. Their findings are published in Science Advances.

Sorting Signals from Silence in Plant Genomes

To put this idea into practice, the researchers examined orthologous gene groups from angiosperms with different histories of genome duplication. Orthologous genes are those that descend from a common ancestral gene, making them useful for comparisons across species. The team quantified how dosage-sensitive each gene group was by comparing the observed number of gene copies with the number expected after a whole-genome duplication.

This comparison relied on correlation coefficients, mathematical measures that reveal how closely two variables track each other. Strong correlations suggested high dosage sensitivity, while weak correlations pointed to genes more tolerant of copy-number changes. Based on these values, the orthologous gene groups were classified into four categories, ranging from the most dosage-sensitive to the least.

The distinctions turned out to matter. Highly dosage-sensitive gene groups showed hallmarks that made evolutionary sense. They were under stronger purifying selection, meaning that harmful changes were more efficiently removed over time. They participated in more protein–protein interactions and were expressed across a broader range of tissues. Most importantly, their genetic signatures displayed clearer peaks corresponding to known whole-genome duplications. This convergence of evidence validated their use as reliable markers for ancient genome duplication events.

In effect, the researchers had identified a subset of genes that remembered the past more faithfully than others.

A Closer Look at the Earliest Flowering Lineages

Armed with these markers, the team revisited the central question: how many ancient whole-genome duplications shaped the ancestry of seed plants and angiosperms? To test competing scenarios, they combined several analytical approaches, including gene tree–species tree reconciliation, gene copy number correlation analysis, and probabilistic models of gene retention.

Two plant species played a crucial role in this investigation. Amborella trichopoda and Aristolochia fimbriata are early-diverging angiosperms that lack whole-genome duplications occurring after the rise of flowering plants. This makes them especially valuable as windows into deep evolutionary history, relatively unclouded by later genomic upheavals.

When the researchers examined the duplication patterns in these lineages, a striking result emerged. There was only one prominent ancient duplication peak. This peak corresponded clearly to the ancestral seed plant whole-genome duplication, the ζ event proposed more than a decade earlier. In contrast, the signal expected for an angiosperm-specific ε event was barely visible.

The numbers told a consistent story. Duplication node ratios associated with the putative ε event were significantly lower than theoretical expectations. When the team looked specifically at dosage-sensitive gene groups, the retention rates for this supposed event were extremely low. Both correlation analyses and probabilistic modeling converged on the same conclusion: the data did not support the existence of ε as an independent whole-genome duplication.

One Ancient Doubling, Not Two

Taken together, the evidence points to a simpler evolutionary history than previously imagined. According to the evolutionary patterns of dosage-sensitive genes, seed plants experienced a single ancestral whole-genome duplication. Flowering plants inherited this legacy, but they did not undergo an additional genome-wide duplication during their early evolution.

This does not diminish the importance of whole-genome duplication in shaping plant diversity. On the contrary, it underscores how profoundly a single event can influence millions of years of evolutionary trajectories. The ζ event appears to have provided a genomic foundation upon which both gymnosperms and angiosperms built their remarkable diversity.

What the study challenges is the assumption that angiosperms required a second ancestral duplication to become successful. Instead, their rise may have depended more on how genes were retained, modified, and regulated after that original duplication, rather than on another wholesale doubling of the genome.

Why This Discovery Matters

Understanding whether flowering plants experienced one or two ancient whole-genome duplications is not an abstract exercise. It reshapes how scientists think about the mechanisms that drive evolutionary innovation. If angiosperms did not rely on an additional genome duplication, then other processes, such as selective gene retention, regulatory changes, and network reorganization, may have played larger roles than previously appreciated.

The study also highlights the importance of choosing the right genetic evidence when probing deep evolutionary time. By focusing on dosage-sensitive genes, the researchers demonstrated that not all genes tell the same story, and that some are far more trustworthy narrators of ancient events. This approach offers a powerful framework for resolving similar debates across the tree of life, where ancient genomic signals are often blurred.

At a broader level, the findings remind us that evolution does not always favor complexity through repetition. Sometimes, a single transformative event, carefully preserved and subtly reshaped, is enough to give rise to extraordinary diversity. In the quiet persistence of dosage-sensitive genes, flowering plants have kept a record of their deepest history, waiting for the right questions to bring it back into focus.

More information: Tao Shi et al, Revisiting ancient whole-genome duplications in the seed and flowering plants through the lens of dosage-sensitive genes, Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aea9797. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aea9797