The North Atlantic does not change gently. Its ecology shifts with seasons and currents, but every so often it lurches, abruptly and decisively, into something new. A team of researchers has traced one such lurch to a single marine heat wave, a brief but powerful event that reshaped ecosystems and food webs across the subpolar North Atlantic. The changes did not fade when the heat did. They persisted, echoing through the ocean and into human lives, and they are still detectable today. The findings, now published in Science Advances, read like a reminder that the sea has a memory, and that sudden extremes can leave marks as deep as any slow trend.

The study asks a deceptively simple question: what happens when the ocean experiences an extreme event that is both widespread and unexpected? The answer, assembled from decades of observations, is that the effects can cascade across species, distances, and years, transforming entire systems in ways that are difficult to foresee.

A Heat Wave That Reached Far Beyond the Surface

Marine heat waves are not merely warmer water. They are disruptions, capable of reorganizing life in the sea with startling speed. The researchers behind this study set out to understand how such events develop and what makes some of them transformative while others fade with fewer lasting consequences.

They found that marine heat waves became more frequent after 2003. Yet frequency alone did not explain impact. As the first author, Dr. Karl-Michael Werner from the Thünen Institute of Sea Fisheries, explains, “We found that more marine heat waves occurred after 2003, but they did not have a similar effect compared to the one in 2003.” Something about that year was different, not just in intensity, but in combination.

The heat wave of 2003 did not remain confined to the ocean. Atmospheric temperatures above the North Atlantic reached record highs, and the effects extended onto land, where Europe experienced deadly atmospheric heat waves that claimed thousands of lives. At sea, the water between western Greenland and the Norwegian coast warmed to record levels, spanning the entire subpolar North Atlantic. This was not a localized anomaly. It was a basin-scale event.

The Perfect Storm in the North Atlantic

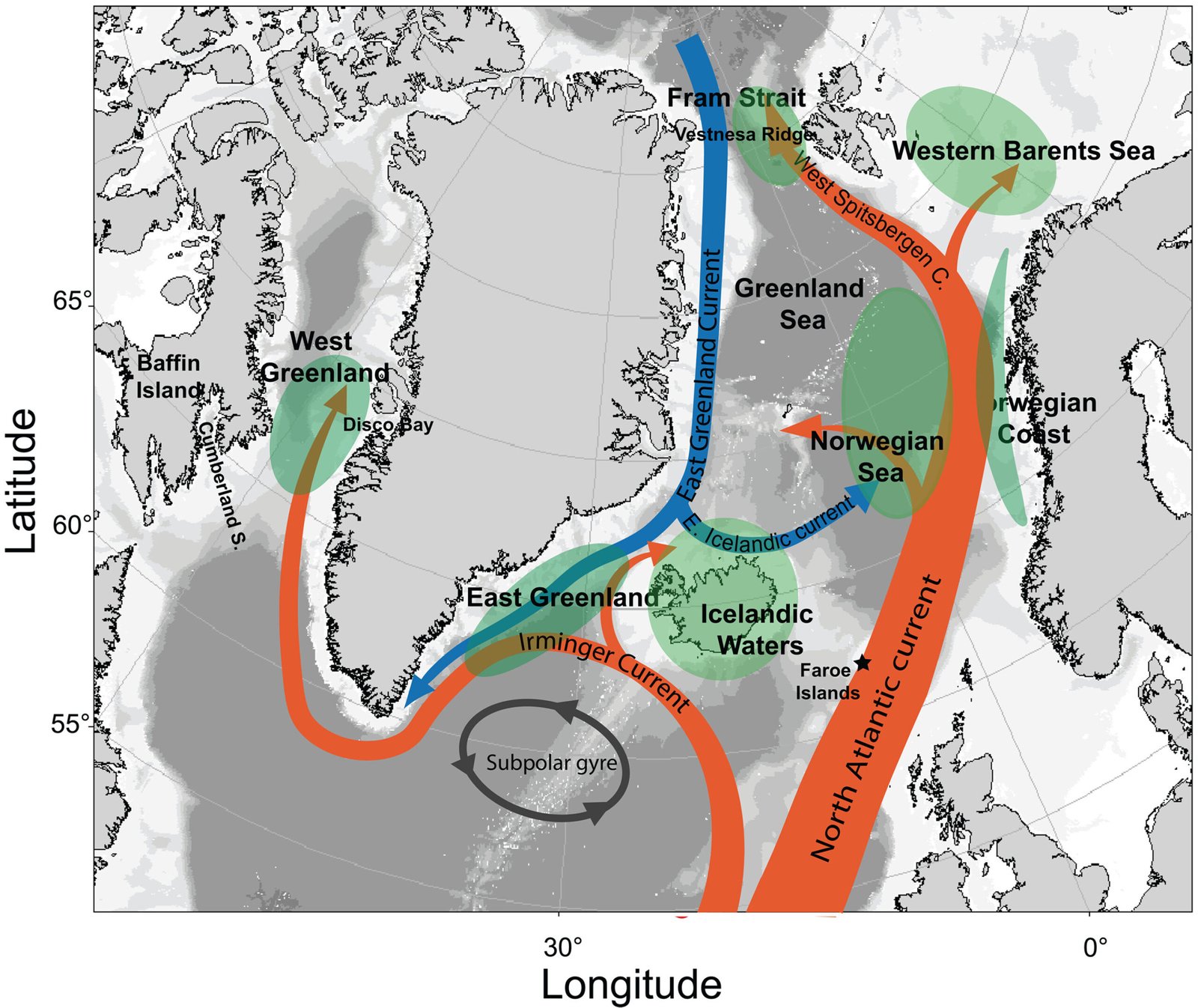

The researchers describe 2003 as a “perfect storm,” a phrase that captures both the rarity and the dramatic consequences of what occurred. In this case, the storm was not a single phenomenon but a convergence. Unusually low amounts of Arctic water flowed southward along the East Greenland coast, while unusually high quantities of warm, subtropical waters entered the North Atlantic between Iceland and Scotland. At the same time, the atmosphere above the ocean heated to unprecedented levels.

Each of these elements alone might have been manageable for the ecosystem. Together, they produced a shock. The combination of atmospheric and hydrographic events drove water temperatures higher than previously recorded across the subpolar region. Life in the ocean, from the smallest algae to the largest whales, was suddenly operating under new rules.

Reading the Ocean’s Long Memory

To understand the scale of the change, the researchers turned to time. They examined around 100 biological time series, drawing on long-term observations that make it possible to distinguish a true shift from natural variability. Among the most important sources was the HAUSGARTEN observatory, part of the Long-Term Ecological Research program run by the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven. In the Fram Strait between Svalbard and Greenland, scientists have been collecting ecological data for 25 years, patiently building a record of life in one of the ocean’s key gateways.

When the team analyzed these records, a pattern emerged with striking clarity. A majority of the examined parameters showed abrupt changes in 2003 or shortly thereafter. The timing aligned across organisms and processes, pointing to a common driver rather than isolated coincidences. The ocean had crossed a threshold.

Winners, Losers, and a Shifting Menu

The heat wave did not affect all species equally. Some struggled, others expanded, and the balance of the food web shifted accordingly. Capelin, a cold-water fish species and the most important subpolar forage fish in the North Atlantic, began to suffer. Warmer-water-loving species such as cod and haddock, by contrast, expanded their distribution northwards, moving into regions that had previously been too cold.

Capelin responded by shifting their spawning areas northwards from south-western Iceland. This relocation, however, came at a cost. Eggs and larvae began drifting toward habitats near the coast off East Greenland, environments to which they were not well adapted. In these unfavorable conditions, their probability of survival dropped. A change intended as a refuge became a risk.

Predators followed the rearranged buffet. Humpback whales, which feed on capelin, benefited from the new distribution. They began appearing much more regularly in South-East Greenland than they historically had, tracking their prey into newly suitable waters. The movement of one species reverberated through others, illustrating how tightly linked the system is.

A Wave That Traveled North and Downward

One of the most remarkable aspects of the study is the distance over which the heat wave’s influence was felt. The Fram Strait lies thousands of kilometers from where the marine heat wave began. Yet the researchers were able to link a warm-water anomaly in the Fram Strait to the original event, arriving roughly two years later. Warm waters moved northwards, carrying with them new organisms and supporting local boreal species.

When these newcomers arrived, they did not simply add to the existing ecosystem. They altered it. The changes were abrupt and extended from the sea surface all the way to the deep ocean floor. Warmer surface waters increased biomass in the upper layers of the ocean. Over time, this material sank, delivering more food to organisms living on and in the sediments, including brittle stars and nematodes.

Yet abundance alone did not guarantee benefit. There are signs that the nutritional quality of the sinking organic matter declined even as its quantity increased. More food, it turned out, did not necessarily mean better food. The deep-sea community received a different diet, with unknown long-term consequences.

The Limits of Prediction in a Living System

The study underscores how difficult it is to predict ecological responses to extreme events. Temperature influences metabolism, growth, and reproduction, and these effects can be estimated. But ecosystems are not collections of isolated species. They are networks of interactions, shaped by who eats whom, where organisms reproduce, and how they move.

As Werner puts it, “Our results show that unexpected extreme events can lead to unpredictable ecological cascades.” Rising temperatures may enable a species to expand northwards, but that does not guarantee success. A fish may encounter new predators, fail to find suitable spawning grounds, or lose access to the prey it depends on. The benefits of warmth can be canceled or reversed by the realities of the food web.

Among the species examined, one stands out as particularly adaptable. Atlantic cod appears to be the most likely beneficiary of the changes observed in the subpolar North Atlantic. It is described as a typical opportunistic predator, able to exploit new conditions effectively. As Werner explains, “It spreads and eats everything it can find, if the conditions allow.” In a reshuffled ecosystem, flexibility becomes a powerful advantage.

Why This Moment in the Ocean Still Matters

The legacy of the 2003 marine heat wave is not confined to the past. Its effects are still detectable today, embedded in species distributions and ecological relationships. This matters because it shows how a single, large-scale extreme event can push an ecosystem into a new state, one that persists long after temperatures return to normal.

For humans, the implications are tangible. Changes in the distribution of fish species alter fisheries and diets built over decades. As Werner notes, “Such an event even impacts us humans because it changes the distribution of fish species we are adapted to fishing and eating for decades.” The study connects physical extremes to social and economic realities, reminding us that marine ecosystems underpin human livelihoods.

More broadly, the research challenges the assumption that gradual warming is the only force shaping the future of the oceans. Sudden extremes can act as turning points, triggering cascades that are difficult to reverse or predict. By revealing how the heat wave of 2003 reorganized life from the surface to the seafloor and from Greenland to the Fram Strait, this work highlights the importance of long-term observation and caution in a changing world. The ocean can change quickly, and when it does, the consequences can last a generation or more.

More information: Karl Michael Werner et al, Major heat wave in the North Atlantic had widespread and lasting impacts on marine life, Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adt7125