For millions of years, the Isle of Wight’s cliffs have guarded secrets from a world long vanished. Fossil hunters and paleontologists know it as one of Europe’s richest sites for dinosaur remains, a place where each tide can reveal traces of ancient life. Now, a remarkable new species has emerged from this landscape: a dinosaur with a striking sail running down its back and tail, unlike anything seen before on the island.

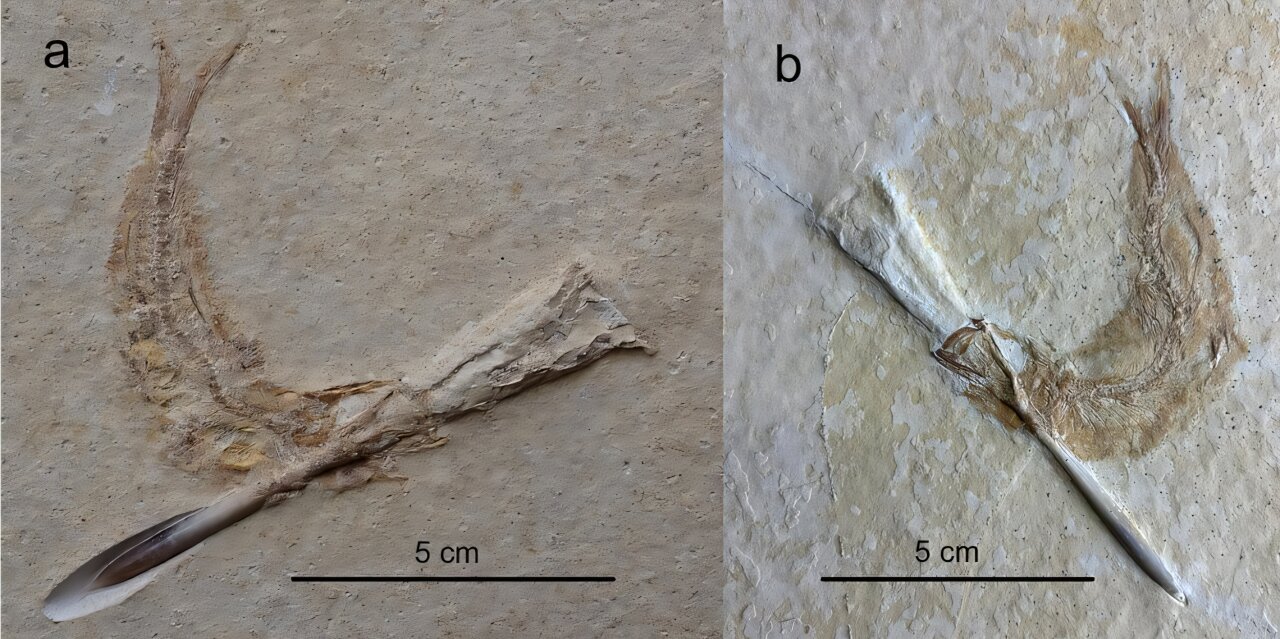

The discovery was made not in the field but in the quiet halls of a museum. Jeremy Lockwood, a retired general practitioner and passionate paleontologist, carefully re-examined bones stored in the collections of the Dinosaur Isle museum. While many specimens had already been studied and categorized, Lockwood noticed something others had missed. The fossils, around 125 million years old, didn’t quite fit the description of any known species from the Isle of Wight.

What caught his eye was extraordinary—long, thin spines rising from the vertebrae, suggesting that this animal carried a dramatic sail-like structure across its body. This was not just another iguanodontian dinosaur. It was something new.

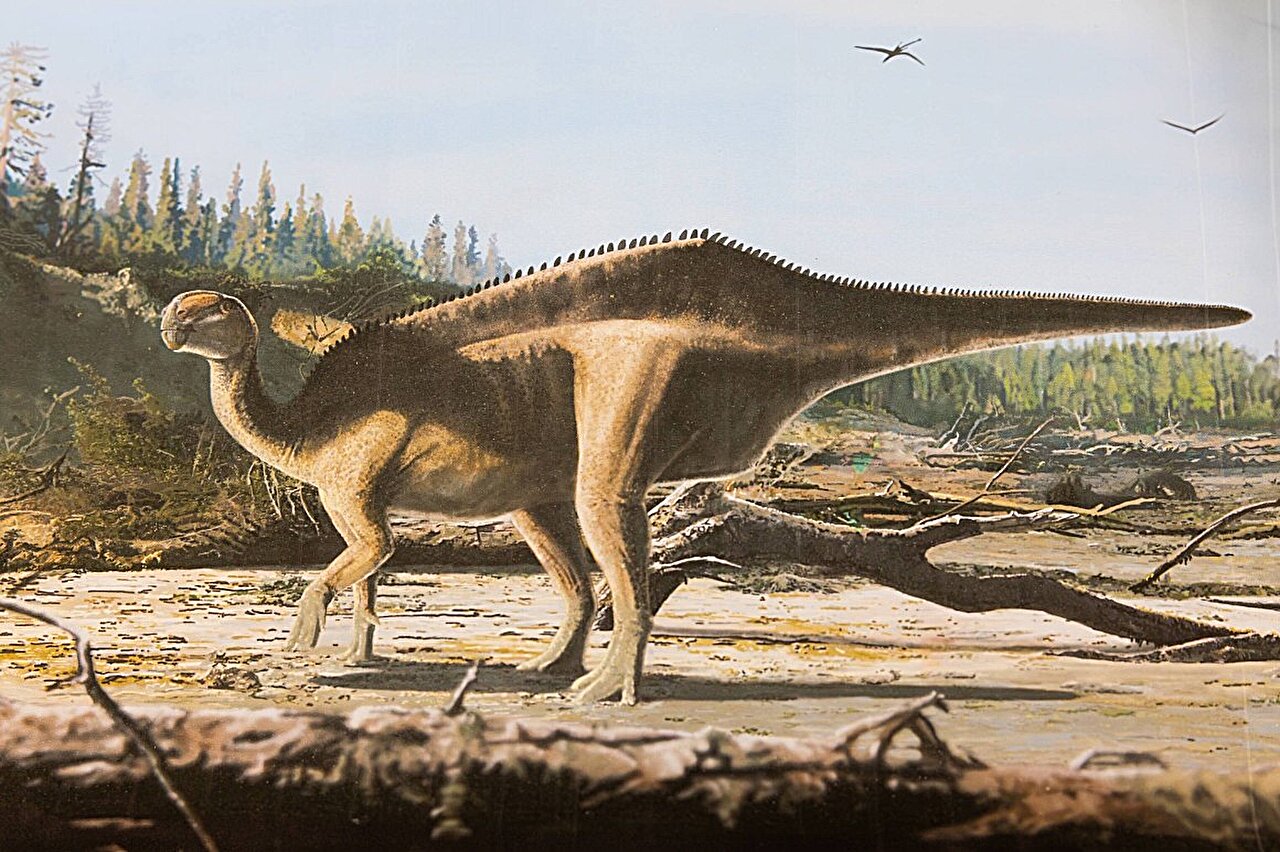

Meet Istiorachis macarthurae

Lockwood’s research led to the identification of a brand-new species, which he named Istiorachis macarthurae. The name is a blend of science and tribute. Istiorachis translates to “sail spine,” reflecting the animal’s most distinctive feature. The second part honors Dame Ellen MacArthur, the world-renowned sailor who set a record for the fastest solo, non-stop circumnavigation of the globe—and who also happens to hail from the Isle of Wight.

The choice of name feels poetic: just as Ellen MacArthur sailed across the oceans, this dinosaur carried its own sail across the prehistoric landscapes of southern England.

The Mystery of the Dinosaur Sail

Why would a dinosaur need such an extravagant feature? Evolution often surprises us with structures that seem more decorative than practical. In the case of Istiorachis, the elongated spines probably supported a striking sail that ran along its back and tail.

Scientists have debated the function of such sails for decades. Some argue they could have helped regulate body temperature, acting like a natural radiator. Others suggest they may have stored fat, serving as an energy reserve. But Lockwood and his colleagues believe the most likely explanation is visual display.

In other words, this sail may have been all about appearances. Just as a peacock’s feathers or a stag’s antlers exist to attract mates or intimidate rivals, Istiorachis may have used its sail to stand out in the crowd. If true, it offers a vivid glimpse into the role of beauty and attraction in dinosaur evolution.

A Window into Evolution

The discovery of Istiorachis does more than add a new name to the dinosaur family tree—it highlights an important evolutionary trend. Paleontologists have found evidence that elongated vertebral spines began appearing in iguanodontians during the Late Jurassic period. By the Early Cretaceous, when Istiorachis roamed, such features had become more common, though extreme examples like this one remained rare.

The hyper-elongation of neural spines—where they grow more than four times the height of the vertebra itself—represents an evolutionary leap. It shows how natural selection and sexual selection together can push anatomy in unexpected directions, shaping creatures that seem almost fantastical by modern standards.

The Role of Museums in Discovery

One of the most striking aspects of this story is that the fossils were not freshly dug from the earth. They had been resting for years in museum collections, thought to belong to other species. It was only Lockwood’s persistence and careful eye that revealed their hidden significance.

As Professor Susannah Maidment of the Natural History Museum in London explained, this discovery is a testament to the value of museum collections. Fossils kept in storage are not just relics—they are scientific treasures, waiting for new ideas, fresh perspectives, and modern techniques to bring them to life again.

Indeed, Lockwood’s work has already transformed our understanding of the Isle of Wight’s ancient inhabitants. Over just five years, he has quadrupled the known diversity of smaller iguanodontian dinosaurs from the island. Istiorachis macarthurae is the latest and perhaps the most visually dramatic addition to this expanding roster.

The Isle of Wight: A Dinosaur Island

The Isle of Wight has long been a hotspot for paleontological discovery. Its eroding cliffs expose layers of rock from the Early Cretaceous, a time when southern England was a warm, lush landscape dotted with rivers and floodplains. Dinosaurs thrived here—herbivores grazing in herds, predators lurking nearby.

Every new fossil found on the island adds detail to this prehistoric ecosystem. The emergence of Istiorachis suggests that these environments were not just functional but filled with creatures evolving remarkable adaptations for survival, competition, and display. The Isle of Wight, it seems, still has countless secrets to reveal.

A Dinosaur That Captures the Imagination

For scientists, the discovery of Istiorachis macarthurae is a breakthrough in understanding evolution and diversity among iguanodontians. But for the public, it sparks something equally powerful: imagination.

It’s easy to picture this dinosaur walking through Cretaceous forests, its sail catching the light of the sun, shimmering like a flag of survival and attraction. Was it a symbol of dominance? A signal of beauty? A display that drew others near? Whatever its purpose, the sail reminds us that dinosaurs were not just giant lizards but creatures of incredible variety and complexity.

The Legacy of Istiorachis

The unveiling of Istiorachis macarthurae is more than a scientific achievement—it is a reminder of the ongoing dialogue between the past and the present. Fossils whisper stories across millions of years, but it takes human curiosity, patience, and imagination to listen.

Lockwood’s discovery shows that even well-known fossil sites can surprise us, and that sometimes the most revolutionary finds come not from new excavations but from looking again at what we already hold. The sail-backed dinosaur of the Isle of Wight is a symbol of both nature’s creativity and humanity’s relentless search for understanding.

And so, Istiorachis lives again, not as bones in a drawer, but as a vivid part of our shared history—an ancient creature whose dramatic sail once caught the eye of its peers, and now captures ours.

More information: Jeremy A. F. Lockwood et al, The origins of neural spine elongation in iguanodontian dinosaurs and the osteology of a new sail‐back styracosternan (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Lower Cretaceous Wealden Group of England, Papers in Palaeontology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/spp2.70034