For centuries, humans have looked up at the night sky and wondered: are we alone? The discovery of thousands of exoplanets in recent decades has only deepened this question, as rocky worlds orbiting distant suns became tantalizing candidates for habitability. With every new detection, especially of Earth-sized planets, astronomers hoped we might finally find a second Earth—a place with oceans, air, and perhaps even life.

The launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in 2021 raised those hopes higher than ever. With its powerful infrared instruments, JWST promised to do something extraordinary: not just detect exoplanets, but actually study their atmospheres. For the first time in history, scientists could begin to analyze the skies of distant worlds, searching for water vapor, carbon dioxide, and even hints of biological activity.

Over the last two years, JWST has not disappointed. From gas giants cloaked in exotic clouds to rocky worlds clinging to fragile atmospheres, its discoveries have both thrilled and sobered astronomers. The latest target, a small planet called GJ 3929 b, carried great promise when it was first detected. Yet JWST’s sharp eyes have now revealed a harsher truth.

A Small Planet With Big Potential

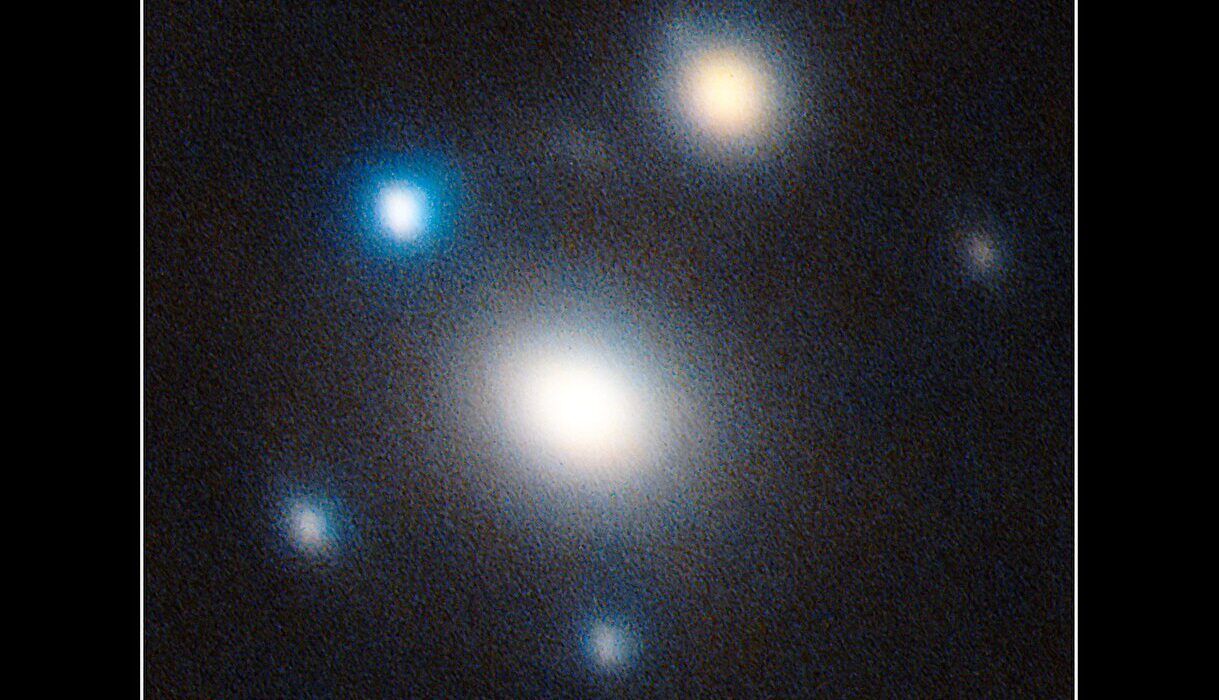

GJ 3929 b was first spotted in 2022 using NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). The tiny dip in starlight during its transit revealed a rocky planet, just a little larger than Earth, orbiting a dim red dwarf star about 48 light-years away. Early calculations put its mass at about 0.43 times that of Earth and its radius at roughly 1.15 Earth’s—numbers that immediately drew excitement.

This was not a gas giant or a bloated super-Earth, but a compact, rocky world. Planets in this regime are particularly interesting because they fall squarely into the “Earth-like” category. They are solid, potentially capable of holding atmospheres, and possibly, in some cases, of supporting life.

When the discovery team announced GJ 3929 b, they wrote with cautious optimism that the world could belong to a new family of rocky planets ripe for atmospheric studies. Scientists waited eagerly for JWST to peer at this small planet, hoping it might join the shortlist of worlds with atmospheres that could, in theory, sustain habitability.

The Harsh Light of Reality

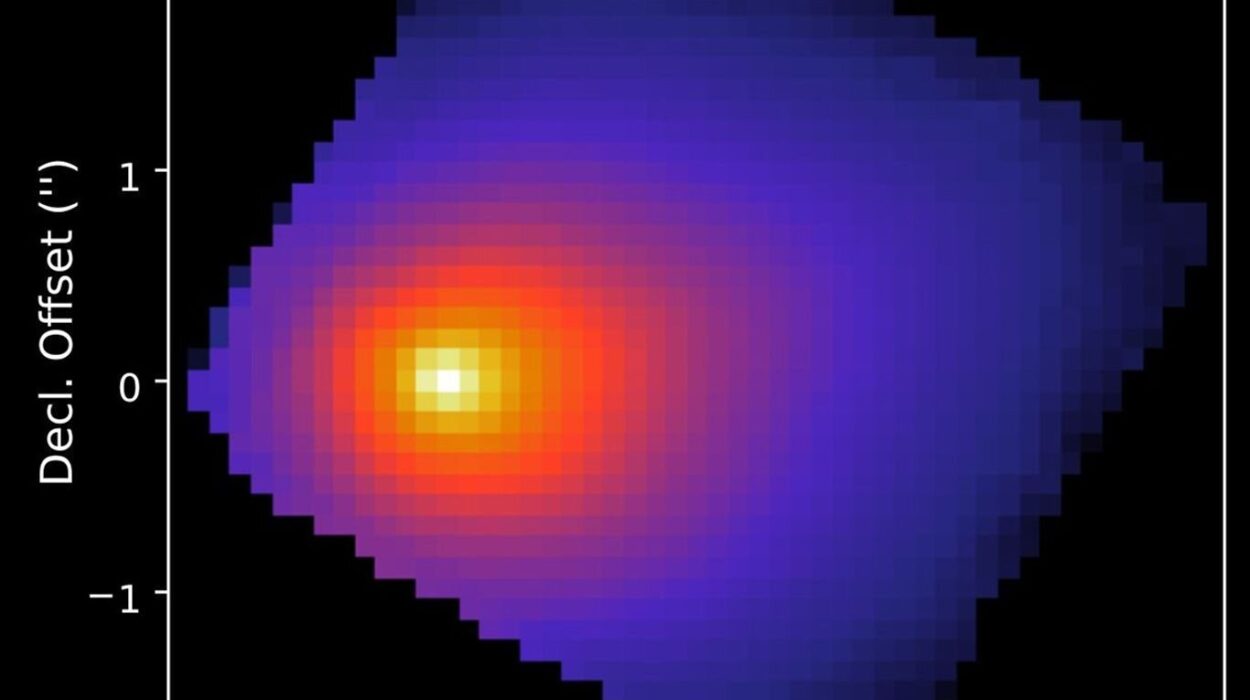

JWST’s Rocky Worlds Director’s Discretionary Time program soon pointed the telescope at GJ 3929 b. Using its extraordinary infrared instruments, the telescope looked for the faint fingerprints of gases in the planet’s atmosphere as it passed in front of its star. If gases like carbon dioxide or water vapor surrounded the planet, JWST would detect their subtle absorption features.

But instead of atmospheric signatures, JWST found silence.

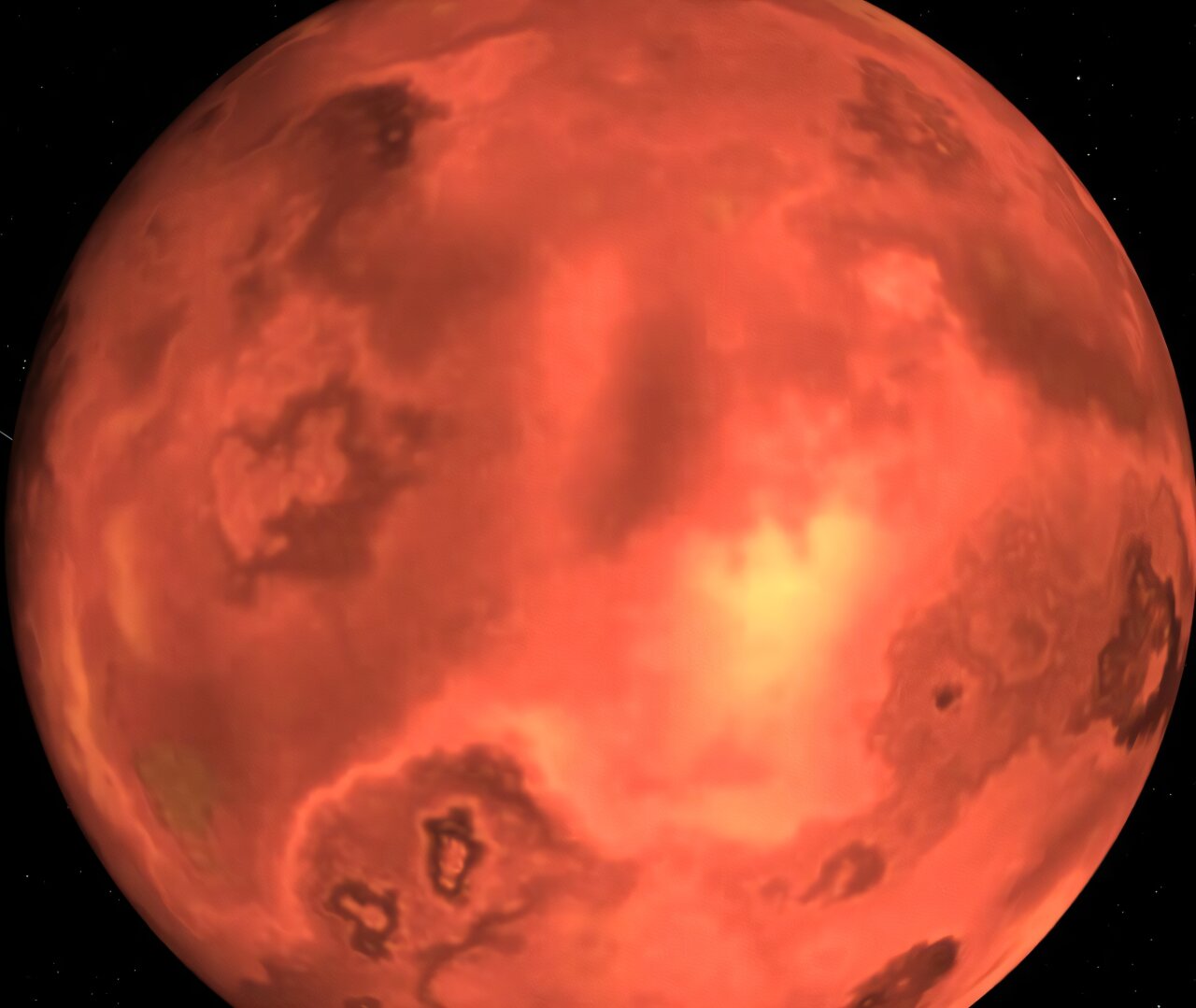

The observations showed that GJ 3929 b’s spectrum was flat, with no sign of a thick atmosphere. The planet’s temperature measurements aligned with that of a bare rock—hot, airless, and exposed directly to its star’s radiation. The research team concluded with high confidence that the world lacks any substantial atmosphere. Even a relatively dense layer of carbon dioxide thicker than 100 millibars—a hundredth of Earth’s atmospheric pressure—was ruled out.

In other words, GJ 3929 b is not a miniature Earth. It is a scorched, lifeless rock.

The Cosmic Shoreline and the Fate of Atmospheres

Why do some rocky planets keep their atmospheres while others lose them? This question drives much of today’s exoplanet research. The case of GJ 3929 b adds an important clue.

Astronomers have developed what is called the “cosmic shoreline hypothesis.” The idea is that the fate of a planet’s atmosphere depends largely on how much high-energy radiation—X-rays and ultraviolet light—it has received from its star over billions of years. Stars, particularly red dwarfs, often flare and bombard nearby planets with intense radiation. If that energy is strong enough, it can heat the upper layers of a planet’s atmosphere, giving particles enough energy to escape into space in a process known as photoevaporation.

For GJ 3929 b, the evidence points clearly toward this outcome. It sits well within the “airless” side of the shoreline, meaning the cumulative radiation has long since stripped away any original atmosphere the planet might have had. Even outgassing from volcanic activity has not been enough to replenish it.

Comparisons with other rocky exoplanets such as TRAPPIST-1b, TRAPPIST-1c, GJ 1132b, and GJ 486b show that GJ 3929 b is even more firmly beyond the shoreline. If those worlds are bare rocks, this one is almost certainly the same.

A Disappointment, But Also a Breakthrough

It is always bittersweet when a planet once thought of as Earth-like turns out to be barren. For those hoping to find signs of life beyond our solar system, news like this can feel like a setback. Yet in science, even negative results are profoundly important.

By confirming that GJ 3929 b has no atmosphere, JWST helps astronomers refine their understanding of which planets can and cannot sustain atmospheres. Each observation adds a critical data point to a growing statistical framework. Over time, these data will reveal the boundaries of atmospheric survival, showing where life-friendly conditions might realistically exist.

As the researchers behind the new study put it, these results will “transform our understanding of how rocky planets form, evolve, and either keep or lose their atmospheres in the intense radiation environments” of their stars.

Red Dwarfs: Hosts of Hope and Hostility

One of the reasons planets like GJ 3929 b are studied so intensely is because of their stars. Red dwarfs make up about 75% of the stars in the Milky Way, making them the most common hosts of exoplanets. Their small size and low brightness make it easier to detect the transits of small planets like GJ 3929 b.

Red dwarfs also live for incredibly long times, potentially trillions of years, compared to the Sun’s 10-billion-year lifespan. That longevity raises the tantalizing possibility that life could have ample time to emerge and evolve on planets orbiting these stars.

But there is a dark side. Red dwarfs are notoriously active, blasting their planets with powerful flares and radiation, especially in their youth. This hostility may strip atmospheres away from close-in planets, leaving them sterile and exposed—exactly what JWST has now seen in GJ 3929 b.

The search for habitable planets around red dwarfs is therefore a delicate balance between hope and harsh reality.

Looking Ahead: The Search Continues

While GJ 3929 b may not be a new Earth, it is not the end of the story. JWST’s Rocky Worlds program will continue targeting other small, rocky exoplanets around red dwarfs. Each one offers a chance to test the cosmic shoreline, to see where atmospheres can survive and where they fail.

The ultimate goal is not just to catalog barren rocks, but to find the rare cases where atmospheres endure—where perhaps water lingers, clouds drift, and climates stabilize. Those are the worlds where life might have a chance.

The story of GJ 3929 b is a reminder that the search for life is a long and patient journey. Each disappointment is also a step forward, narrowing the possibilities and sharpening the focus of discovery. Somewhere among the countless stars, a planet with an atmosphere—and maybe even with life—still waits to be found.

More information: Qiao Xue et al, The JWST Rocky Worlds DDT Program reveals GJ 3929b to likely be a bare rock, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2508.12516