Long before the first dinosaur ever took a step, before forests stretched across continents or birds took to the skies, a different kind of life thrived beneath ancient oceans. That world is largely lost to us now, buried beneath hundreds of millions of years of Earth’s shifting crust. Yet in the quiet rock beds of once-submerged seabeds, nature has left us one of its most enduring and beautiful traces—trilobite fossils.

Trilobites are more than just prehistoric curiosities. They are time travelers in stone. Each fossil offers a snapshot of a vanished world—a living creature frozen in a moment that predates humans by hundreds of millions of years. Studying them is not merely a paleontological endeavor; it is an act of reaching backward into the abyss of time and listening to the whisper of evolution.

The Ancients That Crawled Before the Dinosaurs

Trilobites first appeared in the Cambrian Period, over 521 million years ago, when life on Earth was still experimenting with complex forms. They were among the earliest arthropods—relatives of modern insects, spiders, and crustaceans. At their peak, trilobites dominated the ancient seas. For nearly 270 million years, they thrived in ecosystems across every continent and ocean, from warm shallow coastlines to deeper abyssal plains.

Despite their eventual extinction, their time on Earth dwarfs that of humanity. While humans have existed for around 300,000 years, trilobites persisted for almost a thousand times longer. They lived through massive changes in climate and geography, witnessed the rise and fall of entire marine ecosystems, and endured several mass extinctions before finally disappearing at the end of the Permian Period, about 252 million years ago.

To think of a world ruled by trilobites is to confront an alien Earth—unrecognizable yet utterly real. These small creatures were once the kings of the oceans, crawling, swimming, burrowing, and even seeing with some of the first complex eyes in nature’s history.

The Body of a Time-Walker

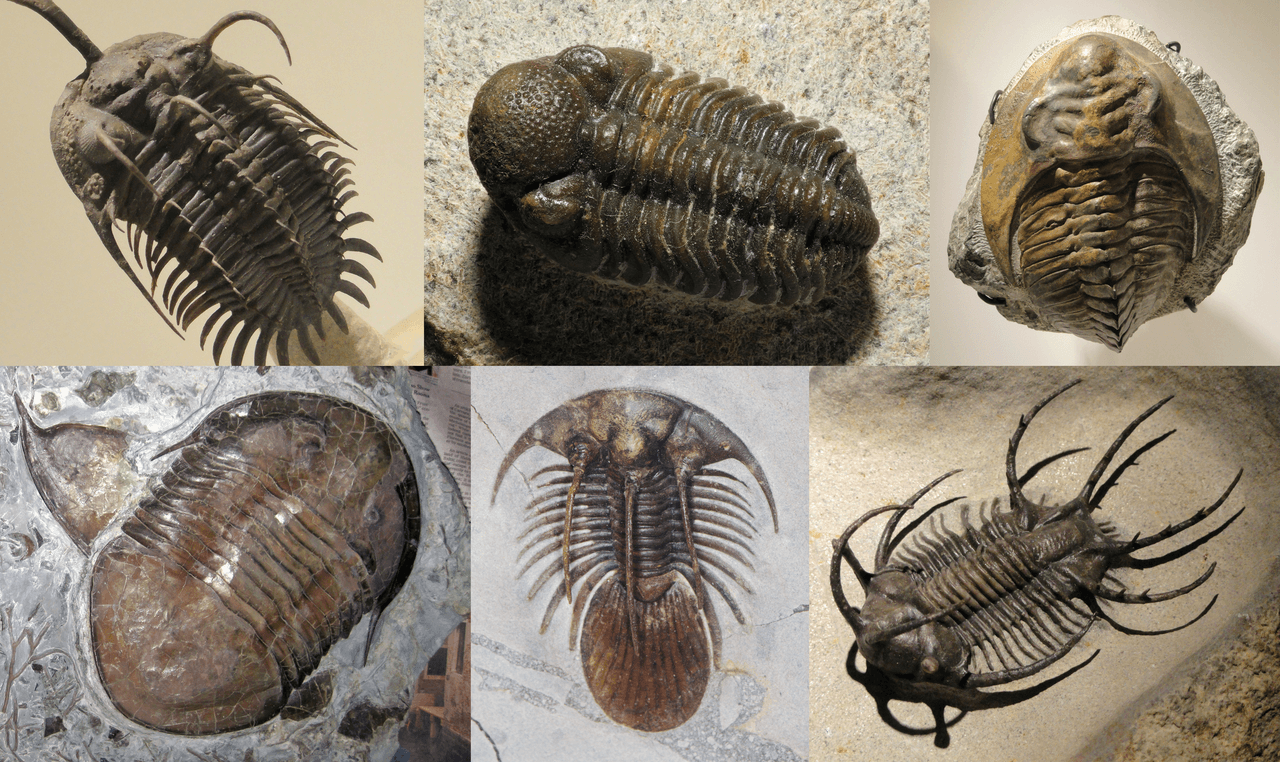

To understand trilobites, one must first understand their anatomy. Their name—“trilobite”—means “three-lobed,” referring not to their head, thorax, and tail, but to the way their bodies are divided longitudinally into three sections: a central axial lobe and two pleural lobes on either side. This structure gave them a distinctive, almost futuristic appearance, as though crafted by a steampunk artisan of evolution.

Despite their ancient origin, trilobites were astonishingly sophisticated. Many species had compound eyes made of calcite, a mineral rather than soft tissue—a rare trait even among fossil organisms. These eyes were capable of wide-angle vision, and some species likely could detect subtle changes in light and movement, allowing them to evade predators or hunt prey.

Their bodies were segmented and often covered in a hard exoskeleton made of chitin and calcite, which could molt and regrow—a behavior not unlike that of modern crabs and insects. Some trilobites evolved elaborate spines for defense or camouflage, while others were sleek and streamlined, indicating active swimming lifestyles. A few developed specialized limbs for digging into sediment, others for filter-feeding or even possibly predation.

Their diversity of form was dazzling. Some species were the size of a grain of rice; others stretched over 70 centimeters (more than two feet) in length. Their shapes ranged from smooth and ovate to wildly ornamented with horns, fans, and spines. Every fossil tells a story—not just of life, but of adaptation and survival in a complex, competitive world.

A Record Written in Stone

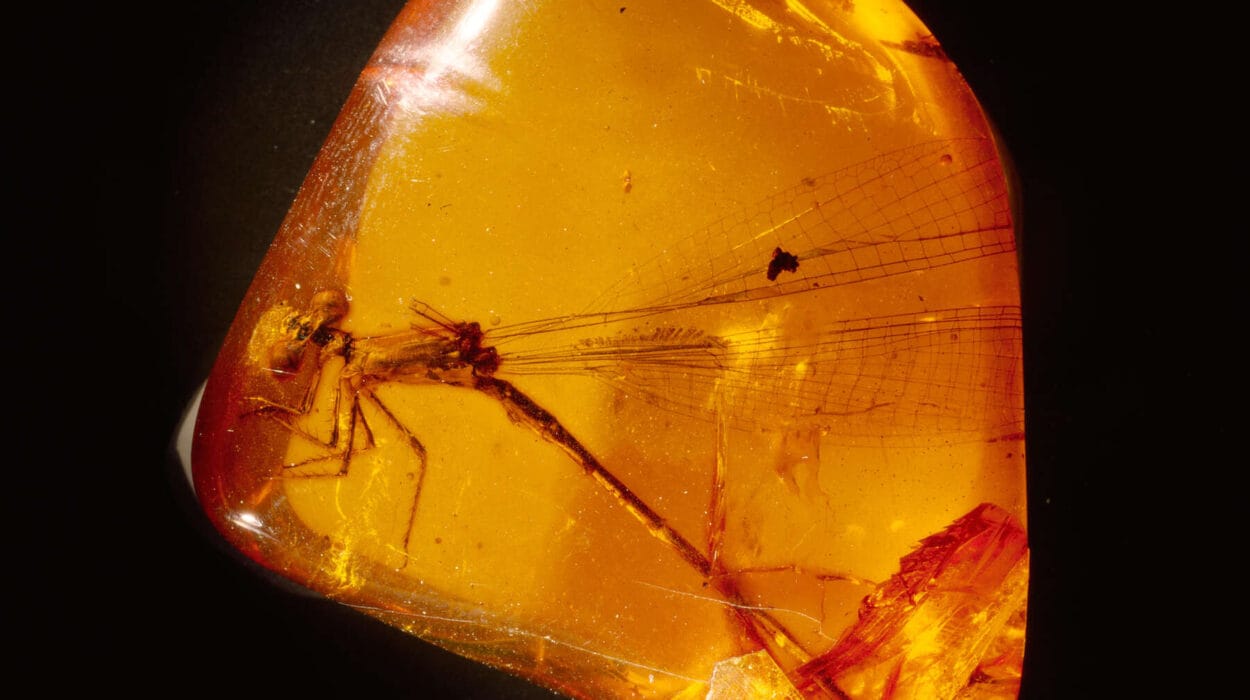

Trilobite fossils are among the most abundant and studied of all invertebrate remains, and for good reason. Their hard exoskeletons fossilize readily, especially in marine sediments. In some layers of Cambrian and Ordovician rock, their remains are so plentiful that the sediment is practically composed of trilobite fragments.

But fossils are not just pretty imprints in stone. They are data-rich documents of natural history. Paleontologists can trace the evolutionary lineage of trilobites with stunning precision, tracking how different body parts changed over time, how new species arose, and how entire lineages vanished in extinction events. They are an evolutionary goldmine.

Moreover, trilobites help scientists date rock layers, a method called biostratigraphy. Because different trilobite species lived during specific geological intervals, their presence or absence in sediment layers serves as a kind of calendar, allowing researchers to piece together the chronology of Earth’s deep past.

Some trilobites are even found preserved in extraordinary detail, their fine features still visible under microscopes. In rare cases, soft body parts such as legs and digestive organs have been preserved, offering rare insight into the internal anatomy of these ancient animals. Such finds are windows into a world that no longer exists, but which once teemed with vibrant life.

Eyes of Stone and the Birth of Vision

Trilobites were pioneers of sight. They are among the first creatures in the fossil record to possess complex, image-forming eyes. These weren’t simple light detectors but fully formed compound eyes, similar in function to those of modern insects.

What’s truly extraordinary is what those eyes were made of: not soft tissue, but crystalline calcite. This mineral-based optical system is unlike anything seen in modern animals. The lenses in trilobite eyes were transparent calcite crystals precisely shaped to reduce distortion—a feat of natural engineering that seems almost too advanced for its time.

Different trilobite species had different eye types—some with lenses packed densely for high-resolution vision, others with more spaced-out eyes suitable for detecting motion. Some had crescent-shaped eyes that curved around their heads, granting nearly 360-degree vision. Others lived in deep or murky water and had reduced or even absent eyes, proving that even then, evolution tailored organisms precisely to their environments.

Studying these ancient eyes doesn’t just tell us about trilobites. It tells us about the origin of sight itself—how natural selection molded the first optical systems, how those systems shaped behavior, and how vision transformed life on Earth forever.

Masters of Adaptation

Trilobites were not a monolithic group; they were a vast and diverse array of species adapted to every conceivable marine niche. Over 20,000 species have been described, and new ones are still being discovered today.

Some trilobites scuttled along the seafloor like armored roaches, feeding on detritus. Others dug burrows and sifted through sediment for organic material. Some may have been filter feeders, capturing plankton from the water column. There’s even evidence to suggest that a few larger trilobites were predators, chasing down smaller invertebrates.

Their adaptability helped them persist through multiple mass extinctions. But even trilobites had limits. While they were survivors of the Late Ordovician and Devonian crises, they couldn’t withstand the Permian-Triassic extinction—the largest biological disaster in Earth’s history, which wiped out more than 90% of marine species. After nearly 300 million years, trilobites vanished, leaving only their fossils behind.

But what fossils they left. Their abundance and variety make them one of the most accessible and beloved of all prehistoric creatures, both to scientists and fossil enthusiasts.

The Human Connection

Trilobites may seem impossibly distant from us in time, but they spark something deep in the human psyche. Perhaps it’s the symmetry of their form, the mysterious complexity of their eyes, or the feeling of holding in your hand a creature that walked the oceans before vertebrates even existed. Fossil collectors the world over treasure trilobites—not merely as specimens, but as time travelers that connect us to our planet’s formative years.

The emotional response to trilobites is not confined to hobbyists. Scientists, too, speak of them with reverence. To discover a new species of trilobite is not simply to add a name to a list. It is to unearth a fragment of evolutionary art, to fill in one more missing tile in the mosaic of life.

In this way, trilobites are more than fossils. They are ambassadors of deep time, reminding us of the countless forms that life has taken, the paths followed and abandoned, the fragility of existence, and the power of adaptation.

Where to Find the Ancient Ones

Trilobite fossils have been found on every continent, a testament to their once-global distribution. Some of the most famous fossil beds include:

- The Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada—home to exquisitely preserved soft-bodied Cambrian fauna, including rare trilobite specimens.

- The Wheeler Formation in Utah, USA—offering a treasure trove of diverse and often beautifully preserved trilobites.

- The Atlas Mountains in Morocco—where commercial and scientific excavations have unearthed ornate, spiny trilobites of jaw-dropping complexity.

- The Czech Republic’s Barrandian area—rich in Silurian and Devonian trilobites, once studied by Joachim Barrande, one of the earliest trilobite researchers.

Each of these sites is a portal to another world. Digging through the rock, brushing away dust from a fossilized carapace, is an act of communion with time itself.

Echoes in the Evolutionary Tree

Though trilobites are long gone, their legacy endures. They were part of the great arthropod radiation that laid the groundwork for many of today’s animals. Their segmented bodies, jointed limbs, and hard exoskeletons are evolutionary traits passed down to millions of species still alive today—from dragonflies to crabs to scorpions.

By studying trilobites, scientists better understand how body plans evolved, how vision arose, how ecosystems changed over eons, and how life responds to catastrophe. They are a chapter in the story of Earth, but also a bridge across evolutionary history.

The Poetry of Deep Time

Holding a trilobite fossil is an act of wonder. You’re not just holding a rock; you’re cradling a moment from a world before language, before trees, before even vertebrate life. It’s easy to forget, in our fast-paced modern existence, that Earth was once ruled by creatures utterly unlike us—yet every bit as real, as complex, as important.

Their fossilized remains remind us of our place in the grand tapestry of life. We are newcomers on a planet shaped by billions of years of evolution. And the trilobite, though long extinct, is one of our oldest teachers.

Its story is one of resilience, of adaptation, of artistry carved by nature’s patient hand. And while their bodies have turned to stone, their legacy still speaks—in every fossil bed, in every museum, in every curious child who lifts a trilobite from the earth and asks, “What was this?”

That question, whispered across half a billion years, still echoes. And the trilobite, silent yet eloquent, still answers: “I was the past. And in knowing me, you know your world.”