Before the dawn of evolutionary thought, the story of life was shrouded in myth, mystery, and miracle. For centuries, humans believed that all living things had appeared exactly as they were, fixed and immutable, created by divine hands in a single moment of supernatural design. The complexity of life was seen not as the product of gradual change, but as a cosmic act beyond question. Fossils were sometimes dismissed as “games of nature,” artifacts of a whimsical planet that had no real past.

But slowly, curiously, bravely, humans began to ask the forbidden question: What if life had a history?

What if the diversity of creatures on Earth—so wondrous, so strange—was not static, but dynamic? What if the world, and all the living beings within it, had changed over time?

That question would prove explosive. It would not only change science. It would change how we see ourselves—our origins, our destiny, our place in the cosmos.

Fossils Speak: The First Clues from Stone

Long before the theory of evolution had a name, fossils whispered secrets to those who dared to listen. In the 17th and 18th centuries, fossil hunters in Europe and North America began unearthing bones and imprints of strange creatures that no longer walked the Earth. They found massive skeletons of lizards that resembled dragons, sea creatures buried on mountaintops, and delicate trilobites fossilized in ancient rocks.

For many, these discoveries were troubling. How could there be remains of animals that didn’t exist anymore? If God had created all life at once, why would he allow some of his creations to vanish? Extinction, at the time, was heretical. The Earth was supposed to be perfect and unchanging.

But fossils refused to be silenced. In the late 1700s, naturalists like Georges Cuvier began to embrace the idea that extinction was real. He examined fossil elephants in Siberia and compared them to living species, concluding that the Earth had once been inhabited by animals that no longer existed. This was a radical break from religious orthodoxy.

Cuvier proposed that catastrophic events, like floods, had wiped out entire species. Though he rejected evolution, his work set the stage for something far more revolutionary: the possibility that species were not eternal. They could appear. They could disappear. And perhaps—they could change.

Darwin’s Dangerous Idea

Charles Darwin’s name is now synonymous with evolution, but his journey to discovery was neither simple nor swift. In 1831, he boarded the HMS Beagle as a young naturalist with a burning curiosity and no idea what lay ahead. During the five-year voyage, he visited the coasts of South America, the Galápagos Islands, Australia, and beyond.

What he saw changed him. He collected thousands of specimens, from fossilized sloths to living finches. On the Galápagos, he noticed that birds on different islands had similar features but distinct beak shapes, seemingly adapted to different diets. He began to suspect that species were not fixed but shaped by their environment over time.

After returning to England, Darwin spent more than two decades assembling evidence. In 1859, he finally published his masterwork: On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.

His central idea was elegantly simple and profoundly unsettling: all life shares common ancestry, and species evolve through natural selection. In each generation, individuals with traits better suited to their environment are more likely to survive and reproduce. Over time, these traits become more common. Populations change. New species arise.

It was biology’s Copernican moment. Just as Copernicus had dethroned Earth from the center of the universe, Darwin dethroned humanity from the center of creation. We were no longer the special, separate pinnacle of life. We were part of it.

The DNA Revolution: Discovering the Blueprint of Life

Darwin explained how evolution happened, but he could not explain why traits were inherited. He had no knowledge of DNA, genes, or chromosomes. He proposed the mechanism of natural selection, but the machinery behind inheritance remained invisible.

That veil was lifted in the 20th century.

In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick—building on the work of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins—revealed the double-helix structure of DNA. This discovery electrified the scientific world. DNA was the molecular code of life, the instruction manual passed from one generation to the next.

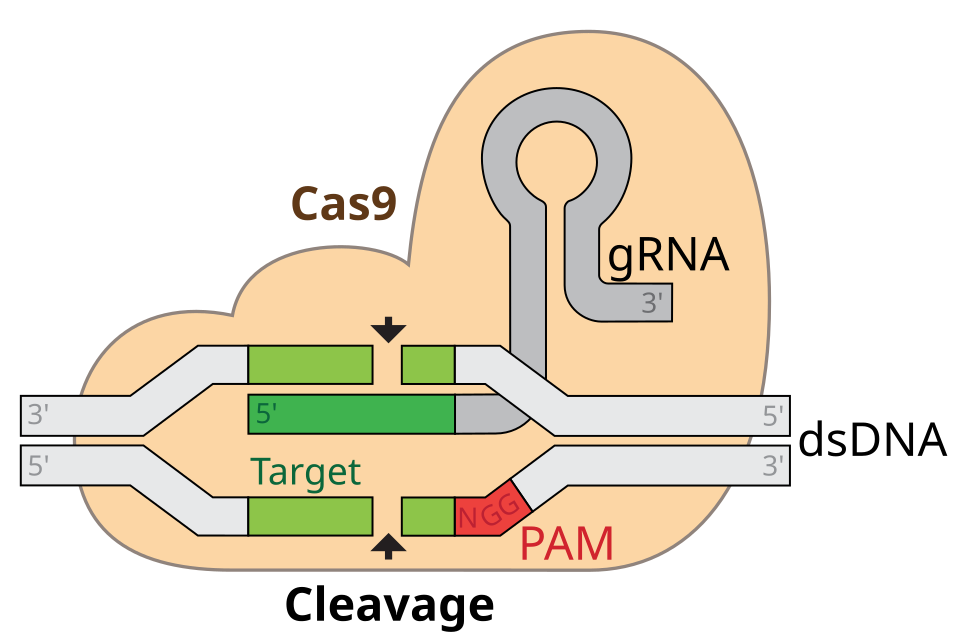

Suddenly, evolution had a molecular foundation. Mutations in DNA—errors in copying—could create variation. Natural selection could then amplify or suppress these variations. The mystery of inheritance was solved, and evolutionary theory was no longer speculative—it was testable, quantifiable, and profoundly precise.

Molecular biology, genetics, and evolutionary theory fused into a unified framework. Scientists could now compare the genomes of different species and trace their evolutionary relationships. The genetic code of humans and chimpanzees, for instance, is over 98% identical—a genetic echo of shared ancestry.

DNA not only explained the past. It gave us tools to predict the future. It showed how bacteria evolve resistance to antibiotics, how viruses mutate, how cancer cells adapt to treatment. Evolution was no longer a theory about ancient bones—it was a force unfolding all around us, every day, in real time.

Transitional Fossils and the Unbroken Chain of Life

For critics of evolution, the fossil record once seemed incomplete. Where were the “missing links,” the intermediates between major groups? Darwin himself admitted the gaps, though he predicted that future discoveries would fill them.

He was right.

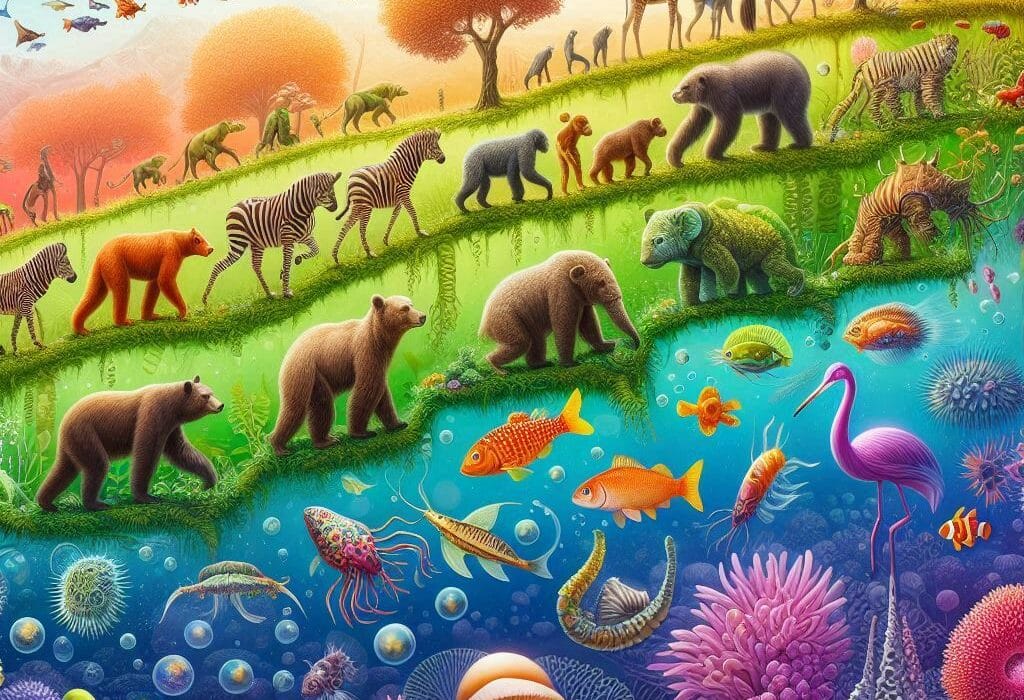

The 20th and 21st centuries brought a cascade of stunning fossil finds. In the Canadian Rockies, paleontologists discovered the Burgess Shale, a 500-million-year-old treasure trove of soft-bodied Cambrian creatures—some bizarre, some strangely familiar. In Greenland, they found Tiktaalik, a fish with limbs and a neck—a perfect transitional form between aquatic and land-dwelling vertebrates.

In China, exquisitely preserved feathered dinosaurs reshaped our understanding of birds, revealing that modern avians are living dinosaurs. In Ethiopia and South Africa, fossils of early hominins—like Australopithecus afarensis, best known through the skeleton nicknamed Lucy—bridged the gap between apes and humans.

These discoveries silenced many doubts. They showed that life’s history was not a collection of isolated snapshots, but a fluid, branching tree, with every twig and branch rooted in a shared past.

Human Evolution: Finding Ourselves in the Fossil Record

Of all the evolutionary discoveries, perhaps none are more emotionally charged than those that reveal our own origins. Where did we come from? What makes us human?

In the 19th century, the idea that humans evolved from apes was scandalous. Many found it degrading to suggest that we shared ancestry with other primates. But fossil and genetic evidence told a consistent story: humans did not descend from modern apes but shared a common ancestor with them.

Over millions of years, our ancestors evolved upright posture, tool use, and complex language. The human story includes many extinct relatives—Homo habilis, Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis—and is more tangled than once believed.

Genetic studies revealed that modern humans interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans. Their DNA lives on in us. We are not a single, pure lineage, but a mosaic—a legacy of encounters, migrations, and adaptations.

This understanding reshapes not just science, but identity. It reveals that race is a social construct, not a biological reality. It shows that all humans share an African origin, and that the diversity we see today is a relatively recent, superficial veneer.

Evolution in Real Time: Watching Change Unfold

For many, evolution once seemed like ancient history—something that happened in the distant past, too slow to observe. But science has shown that evolution is not a relic. It is alive.

In the Galápagos Islands, scientists tracked changes in finch beak size over just a few generations, tied directly to food availability. In urban centers, species are evolving to adapt to pollution, artificial light, and concrete landscapes. In medicine, the evolution of antibiotic resistance threatens to undo decades of progress.

The COVID-19 pandemic offered a dramatic example. As the SARS-CoV-2 virus spread across the globe, it mutated rapidly. Variants like Delta and Omicron emerged, each shaped by selection pressures. Vaccines, immune responses, and public health strategies co-evolved in real time with the virus.

This is evolution in action—not theoretical, but urgent, practical, and deeply relevant to our survival.

The Evolution of Evolution: A Theory That Grows

Like all great ideas, evolution itself has evolved. It began as a daring hypothesis. It grew into a robust scientific theory, supported by fossils, anatomy, embryology, and molecular genetics. But it didn’t stop there.

Modern evolutionary theory incorporates epigenetics, which explores how genes can be switched on or off by environmental factors. It embraces horizontal gene transfer, especially in microbes, which blurs the boundaries of species. It recognizes the role of symbiosis, such as how mitochondria—powerhouses of our cells—were once free-living bacteria.

The tree of life now looks more like a web—a complex, reticulated network of relationships. And yet, the core insight remains: all life is connected. All creatures on Earth share a common origin.

Evolution is not just a biological theory. It is a philosophical revelation. It tells us that change is the rule, not the exception. That complexity can arise from simplicity. That intelligence, emotion, and morality are not gifts from the outside but emergent properties of nature itself.

Cultural and Religious Shifts: Evolution Beyond Science

The impact of evolutionary discovery extends far beyond the laboratory. It has forced religion, philosophy, and culture to grapple with profound questions.

Some saw Darwin’s theory as a threat to faith. Others saw it as a deepening of spiritual awe. Evolution does not diminish the wonder of life—it magnifies it. It reveals a universe that creates through time, that sculpts intelligence from dust, that writes poetry in the spiral of DNA.

In literature, art, and ethics, evolution has left its mark. It has influenced existential philosophy, environmentalism, and even politics. Debates over education and curriculum still rage, particularly over whether evolution should be taught as fact—which it is—or as just another “theory.”

But the evidence is overwhelming. The discoveries have accumulated, converged, and reinforced each other across disciplines. To reject evolution today is not to stand for tradition, but to turn away from the light of understanding.

Why Evolution Matters Now

In a world facing climate change, mass extinction, pandemics, and technological upheaval, the lessons of evolution have never been more vital. Evolution teaches us that life is fragile, resilient, adaptable. It shows us that change is inevitable—but survival is not.

Understanding evolution equips us to conserve biodiversity, combat disease, and navigate our own ethical evolution as a species capable of reshaping the planet. It reminds us that we are not separate from nature but expressions of it.

And it offers humility. We are the product of countless ancestors, shaped by forces we did not choose. We are dust and stars, ape and angel, chance and necessity. Evolution does not rob us of meaning—it roots us in it.

The Endless Frontier of Discovery

The story of evolution is not finished. New fossils are unearthed every year. Genomes are sequenced. Ancient DNA is extracted from permafrost and cave bones. Artificial intelligence is helping to reconstruct the tree of life. Space exploration may soon extend evolutionary inquiry to other planets and moons.

We stand at the edge of an unfolding mystery—a living, breathing, evolving universe that still has secrets to tell.

Darwin began the journey. Generations of scientists have carried it forward. And now it belongs to all of us: the story of life, the story of change, the story of us.