In the early 19th century, the natural world was a puzzle without a clear solution. People saw the diversity of life—the countless species of birds, fish, insects, mammals, trees, and fungi—and many believed they had always existed exactly as they were, designed by divine hands. The idea that species could change, adapt, or emerge from others was not only unpopular but dangerously heretical.

Yet, for those who looked closely, the world whispered secrets. Fossils of strange creatures were being unearthed that resembled nothing alive. Layers of rock showed a history written in stone—older layers containing simpler life forms, higher layers containing more complex ones. Why would a benevolent creator bury such clues unless there had been change over time?

Amid this swirling uncertainty, a young English naturalist boarded a ship in 1831. His name was Charles Darwin, and though he did not yet know it, the voyage he was about to take on the HMS Beagle would set in motion a revolution in human understanding.

Darwin’s Dangerous Journey

As the Beagle sailed along the coasts of South America and the Galápagos Islands, Darwin gathered specimens, made observations, and filled notebooks with ideas. He saw that different islands had similar animals—mockingbirds, finches, tortoises—but with subtle variations. He saw fossils of giant armadillo-like creatures buried beneath plains where their smaller relatives still roamed.

The deeper he looked, the more he realized that species were not fixed. They seemed to change with their environment, to adapt, to diverge. But how?

Returning to England, Darwin spent over 20 years developing his theory before daring to publish it. In 1859, when “On the Origin of Species” was finally released, it didn’t just challenge the scientific establishment—it challenged humanity’s place in the universe. Darwin proposed that all species evolved through natural selection, a process where individuals with advantageous traits survived and reproduced, passing those traits on. Over time, this could lead to gradual change—or even new species.

The book sold out quickly. It was debated, ridiculed, praised, feared. But even as arguments raged in churches, parlors, and lecture halls, the idea took root. Darwin had done something extraordinary: he had unified biology with a single, powerful explanation.

Still, at the time, Darwin’s theory was only that—a theory. Brilliant, logical, and supported by countless observations, but lacking something crucial: direct proof.

The Fossils That Spoke from the Past

To truly prove that evolution had occurred, scientists needed evidence that could bridge the gap between theory and reality. One of the first and most compelling sources came from the ground beneath our feet: fossils.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, paleontologists began to uncover fossils that showed transitions—creatures that seemed to blend features of two different kinds of organisms. In 1861, just two years after Darwin’s book, a remarkable fossil was found in Germany: Archaeopteryx, a feathered dinosaur with both bird and reptile features. It had wings and feathers like a bird but teeth and a long bony tail like a reptile.

Here was physical evidence of a transitional form—a snapshot of evolution in action.

More followed. In the fossil record, scientists traced the evolution of the horse, from small, forest-dwelling ancestors with four toes to large, single-hoofed animals adapted to open grasslands. They discovered transitional whales, like Ambulocetus and Pakicetus, showing how land-dwelling mammals returned to the sea. They found ancient hominins, from Australopithecus to Homo habilis to Neanderthals, each showing a step in the journey from ape-like ancestors to modern humans.

Fossils told a story, not in human words but in stone. They showed that life had changed, that new forms emerged, that old forms vanished. They revealed a tree of life with branches reaching back millions of years.

Yet skeptics remained. Could these fossils really prove common descent? Might they be isolated curiosities, not proof of a grand process?

Science needed more. And so it kept digging—not only into the Earth, but into life itself.

Embryos and Echoes of the Past

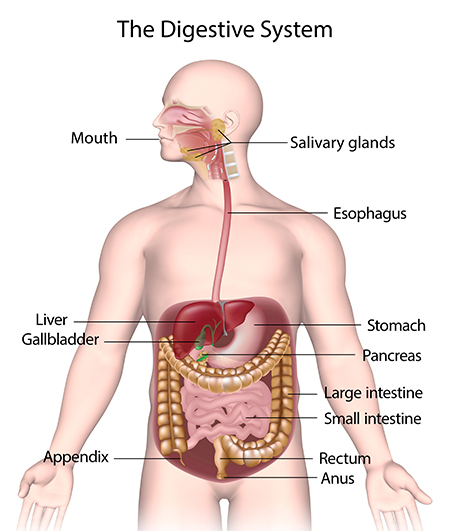

While fossils gave snapshots of ancient life, embryology revealed echoes of ancestry hidden inside the womb.

In the 19th century, biologists like Karl Ernst von Baer and Ernst Haeckel observed that embryos of different animals often looked remarkably similar in early stages. A human embryo, a fish embryo, and a bird embryo all passed through stages that included gill-like slits and tails. Why would a human embryo have such features if not for a shared ancestry?

Though some of Haeckel’s drawings were exaggerated, the central idea held true: development recapitulated descent. Organisms carried within them not only the blueprint for life but traces of their evolutionary history. Tiny muscles, bones, or organs would form in embryos and then vanish before birth—ghosts of ancient ancestors.

Humans, for example, grow fine body hair in the womb, only to lose most of it before birth. We develop muscles to move our ears—useful in alert animals like dogs, but largely vestigial in humans. We even have a tailbone, a remnant of our primate heritage.

Embryology told a story not in bones but in biology. The more scientists studied development, the more they saw that evolution was written into every life from the moment it began.

Comparative Anatomy: The Blueprint of Change

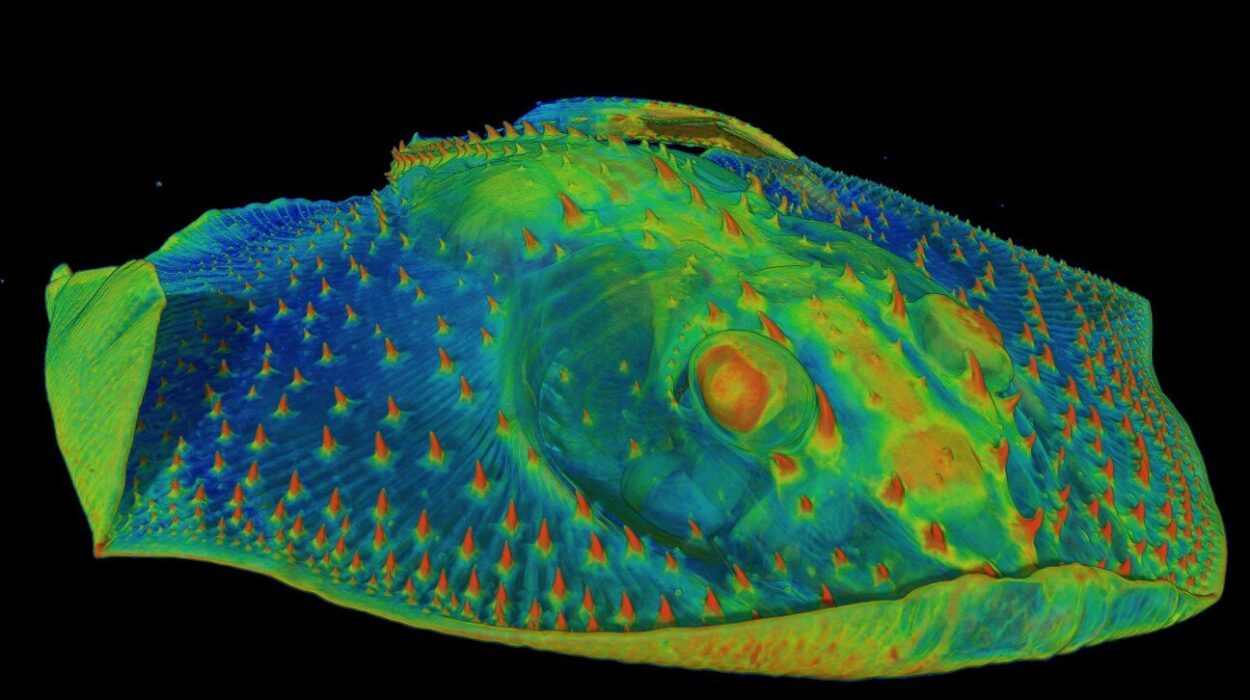

Another powerful line of evidence came from comparative anatomy—the study of body structures across species.

Scientists noticed that vastly different animals often shared similar anatomical features, even when those features had different functions. The arm of a human, the wing of a bat, the flipper of a whale, and the leg of a dog all had the same underlying bone structure: humerus, radius, ulna, carpals, metacarpals, phalanges.

These were not coincidental similarities. They were homologous structures, evidence of descent from a common ancestor. Over time, evolution had modified these structures to serve new purposes, but the blueprint remained.

Even vestigial organs—body parts that served no apparent purpose—made sense in an evolutionary framework. Whales had tiny, hidden pelvic bones, remnants of ancestors that once walked on land. Blind cave fish had eyes that never developed. Humans had an appendix that, while not entirely useless, was far less functional than in our herbivorous ancestors.

Anatomy whispered of kinship across time. Evolution had not built new creatures from scratch—it had modified existing plans, generation after generation.

The Genetic Code: Cracking the Molecular Mirror

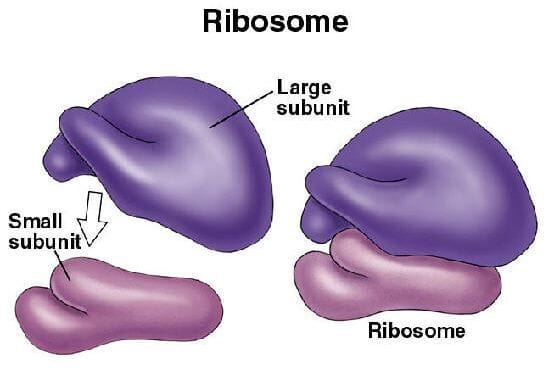

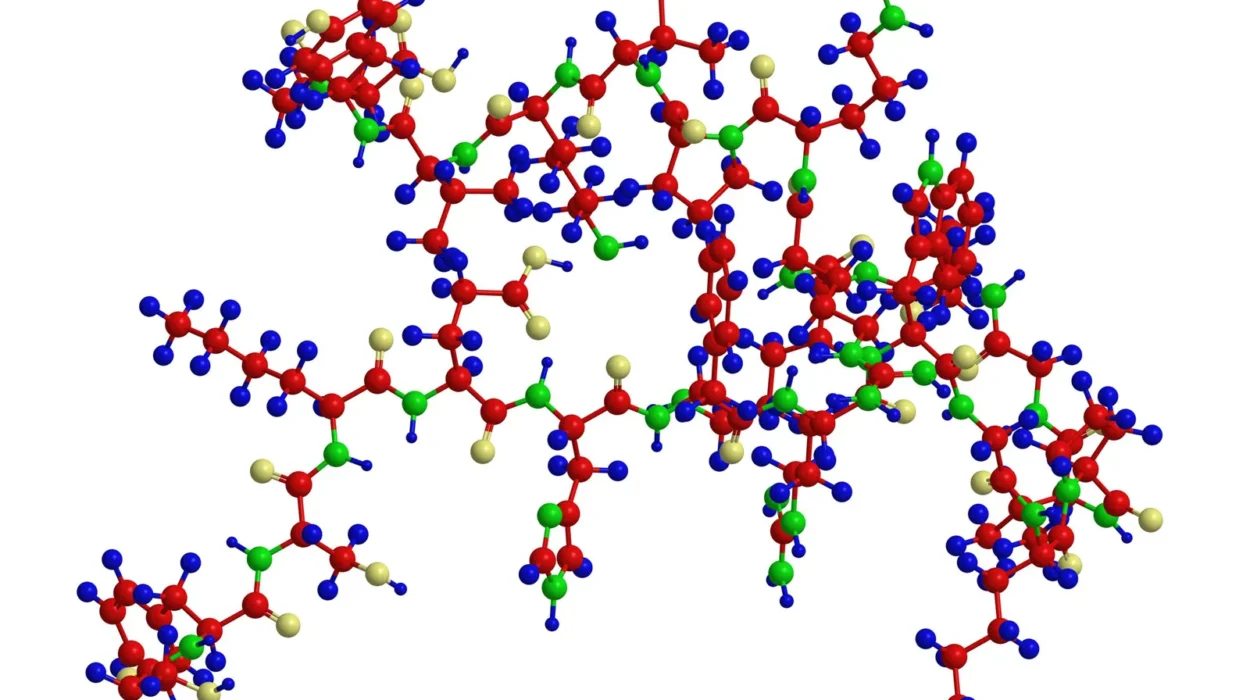

The final and most definitive proof of evolution came not from fossils or anatomy, but from genetics—the discovery that every living thing carries within it a molecular record of its ancestry.

In the mid-20th century, scientists cracked the structure of DNA. They discovered that genes—the sequences of nucleotides in DNA—determined the traits of organisms, from eye color to the number of limbs.

As molecular biology advanced, scientists could now compare the DNA of different species. What they found was stunning: closely related organisms had more similar genes.

Chimpanzees and humans share over 98% of their DNA. Dogs and wolves share even more. Even vastly different creatures—like whales and hippos—showed deep genetic similarities, reflecting a shared evolutionary past.

DNA became a time machine. Mutations—tiny changes in the genetic code—occur at a relatively steady rate over time. By comparing DNA sequences, scientists could estimate when two species diverged from a common ancestor. These molecular clocks aligned beautifully with the fossil record, adding a layer of precision to evolutionary timelines.

Even “junk DNA”—once thought useless—offered proof. Many species shared identical non-functional DNA segments, inherited from common ancestors. These weren’t needed for survival, so why would so many species have the same broken code unless they inherited it?

Evolution was no longer a theory in the speculative sense. It was a theory in the scientific sense—an overarching explanation backed by overwhelming evidence, predictive power, and tested observations.

Evolution in Action: Watching Nature Change

For a long time, critics argued that evolution was too slow to observe. But as the 20th century progressed, scientists began to see evolution happening in real time.

On a remote group of islands called the Galápagos, biologists Peter and Rosemary Grant studied finches over decades. They found that droughts, food shortages, and environmental changes could shift beak size and shape in just a few generations. Natural selection wasn’t theoretical—it was measurable.

In hospitals, bacteria evolved resistance to antibiotics. Tuberculosis and gonorrhea strains that were once easily treated became deadly again. In agriculture, insects developed resistance to pesticides. In wild populations, fish matured earlier due to overfishing. Evolution was responding to human pressures with alarming speed.

Viruses evolved too. Influenza changed each year, requiring new vaccines. HIV evolved resistance to antiviral drugs. COVID-19, a novel coronavirus, mutated into variants that spread more quickly.

We no longer had to imagine evolution. We could watch it happening—in labs, in forests, in oceans, in cities.

From Controversy to Consensus

Despite mountains of evidence, evolutionary theory still faces cultural and religious resistance in parts of the world. But within the scientific community, evolution is no longer controversial. It is the unifying foundation of modern biology.

Every major field—genetics, paleontology, embryology, ecology, anthropology—rests on evolutionary principles. It explains the shape of life, the complexity of ecosystems, the rise and fall of species, the origin of diseases, the potential of medicine.

Evolution is not about chaos or randomness. It is about adaptation, inheritance, and the slow sculpting hand of time. It reveals that all life is connected, that humans are not separate from nature but part of a grand, ancient tapestry.

The Human Story Within the Evolutionary Story

Perhaps the most profound proof of evolution is found in ourselves.

Our bodies carry traces of our past. Our DNA whispers of kinship with every living thing. Our minds, shaped by millions of years of adaptation, still carry instincts from when we hunted and gathered under ancient skies.

We walk upright because our ancestors once stood on the savannah. We see in color because fruit once ripened in trees. We speak, build, and imagine because natural selection favored complex brains.

The human story is not separate from evolution—it is its latest chapter. Our understanding of evolution has allowed us to look back, not just hundreds or thousands of years, but millions. It has revealed how the ape became human, how the fish became amphibian, how the single cell became conscious.

And now, with that knowledge, we stand at a crossroads. We can destroy or preserve. We can manipulate genes or let life take its course. We can act with arrogance or humility.

A Theory, Proven and Alive

Evolution was once a radical idea. Now, it is a proven reality, supported by fossil evidence, molecular biology, embryology, observable adaptation, and the convergence of disciplines across science.

It is not just an idea about biology. It is a window into the very nature of change, of time, of life itself.

Darwin, in the final lines of On the Origin of Species, wrote of life “with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one… from so simple a beginning, endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

He was right. And over the decades, science has shown that his vision was not only poetic—it was true.

Evolution is no longer a question of belief. It is a matter of evidence, seen in the rocks, the genes, the cells, the skies. It is a reminder that we are part of something vast, ancient, and still unfolding—a living story written in the very code of life.