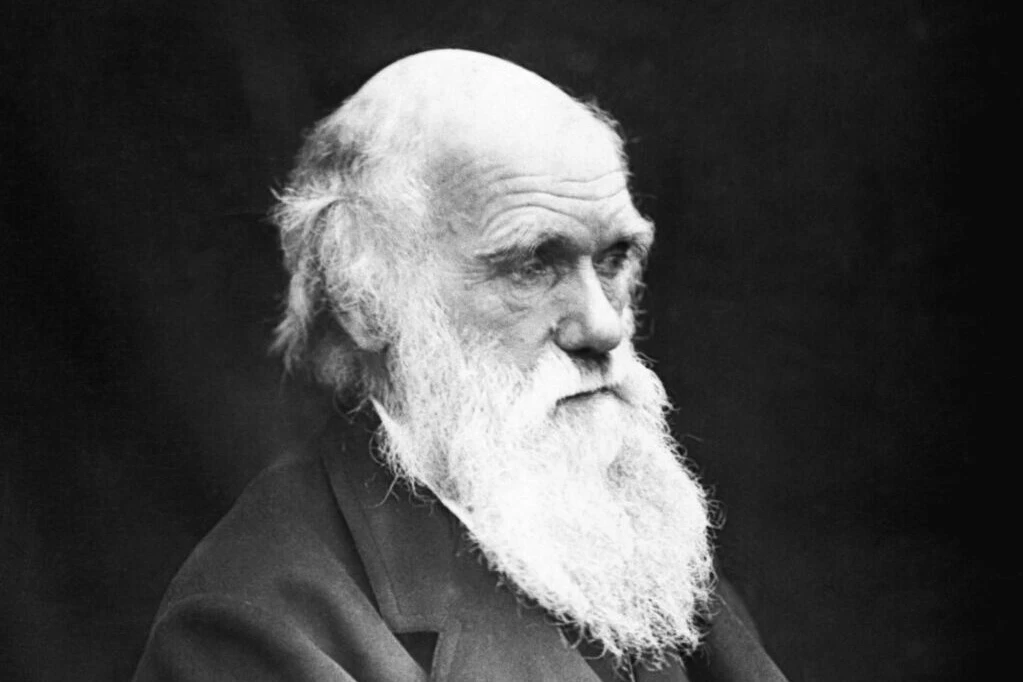

Charles Robert Darwin was born on February 12, 1809, in the quiet market town of Shrewsbury, England. He entered the world into comfort and privilege, the fifth of six children in a prosperous, well-educated family. His father, Robert Darwin, was a respected physician, a man of great size and greater intellect. His mother, Susannah, died when Charles was just eight years old, but the house remained bustling with siblings, servants, books, and natural curiosities.

The boy who would grow up to revolutionize biology wasn’t a prodigy. He didn’t blaze with early intellectual brilliance. He wasn’t particularly driven. In fact, young Charles was more interested in collecting beetles and watching birds than in studying Latin or Greek. He was quiet, introspective, and dreamy—a child more at home in the fields than in the classroom.

His early education at Shrewsbury School was uninspiring. He hated the rote learning, the memorization of rules and classical texts. His teachers considered him lazy and unmotivated. But Darwin was already developing a different kind of mind: observant, methodical, curious, and tenacious. These qualities, unnoticed in the schoolroom, would someday change how humanity sees itself.

A Medical Student Who Fainted at Surgery

In 1825, at the age of sixteen, Charles was sent to Edinburgh University to study medicine. His father, hoping Charles would follow in the family tradition, imagined a future of scalpels and stethoscopes. But Charles was horrified by the bloody realities of nineteenth-century surgery, performed without anesthetic. He fainted at the sight of an operation and recoiled from human anatomy lectures. Medicine, it turned out, was not his calling.

Instead, he gravitated toward the natural sciences. Edinburgh had a rich scientific community, and Charles soaked it in. He joined the Plinian Society, a student group devoted to biology and natural history. There, he conducted his first original investigations—on marine invertebrates, of all things. He also became friendly with a freed Black slave named John Edmonstone, who taught him how to preserve animal specimens, a skill that would later serve him well.

Eventually, realizing that Charles had no heart for medicine, his father suggested the church. Becoming a country parson, after all, was a respectable life path for a young gentleman with no particular ambition. Charles agreed, and in 1828, he entered Christ’s College at Cambridge to prepare for ordination.

The Gentleman’s Naturalist

At Cambridge, Darwin met men who would shape his mind and career forever. Chief among them was the botanist John Stevens Henslow, who saw in Darwin not just a listless student, but a sharp and earnest naturalist. Henslow became a mentor, inviting Darwin on field excursions and encouraging his scientific curiosity. Darwin also read widely during this period, especially the writings of Alexander von Humboldt, whose poetic descriptions of nature’s grandeur inspired a longing in Darwin for adventure.

He passed his final exams without distinction, but with Henslow’s recommendation, Darwin was offered a chance that would redefine his life—and the history of science. In 1831, Captain Robert FitzRoy of HMS Beagle was seeking a gentleman companion to join a two-year survey expedition around South America. Darwin, young and unmarried, was ideal. His father initially opposed the idea, calling it a waste of time, but eventually relented.

On December 27, 1831, Darwin boarded the Beagle. The voyage would last not two years, but nearly five. He was 22 years old.

The Voyage That Changed Everything

The Beagle’s voyage was not a pleasure cruise. It was a rigorous naval expedition charged with charting coastlines and collecting navigational data. Darwin was officially the ship’s naturalist, but unofficially, he was its philosopher, geologist, zoologist, and ever-curious observer.

As the Beagle traced the southern coasts of South America, rounded Cape Horn, and visited the Galápagos, Tahiti, Australia, and other remote lands, Darwin found himself immersed in unfamiliar and wondrous ecosystems. He meticulously documented plants, animals, fossils, and geological formations, filling notebooks with observations.

In Argentina, he discovered fossilized bones of enormous extinct mammals embedded in cliffs beside seashells, suggesting profound shifts in the Earth’s surface over time. In the Andes, he found seashells high in the mountains, evidence of tectonic uplift. On the Galápagos Islands, he noticed slight but significant differences in birds and tortoises from one island to the next, and he puzzled over why island species resembled their mainland counterparts, yet were clearly distinct.

He didn’t yet have answers. But the seeds of a revolutionary theory were quietly taking root.

The Dangerous Idea Emerges

When Darwin returned to England in 1836, he was a changed man. He had sailed around the world and seen nature’s diversity with fresh eyes. The voyage had not just expanded his understanding—it had shattered his previous assumptions.

Over the next two decades, Darwin would build, refine, and wrestle with an idea so explosive, so contrary to traditional beliefs, that he kept it largely to himself for years. The idea was evolution by natural selection.

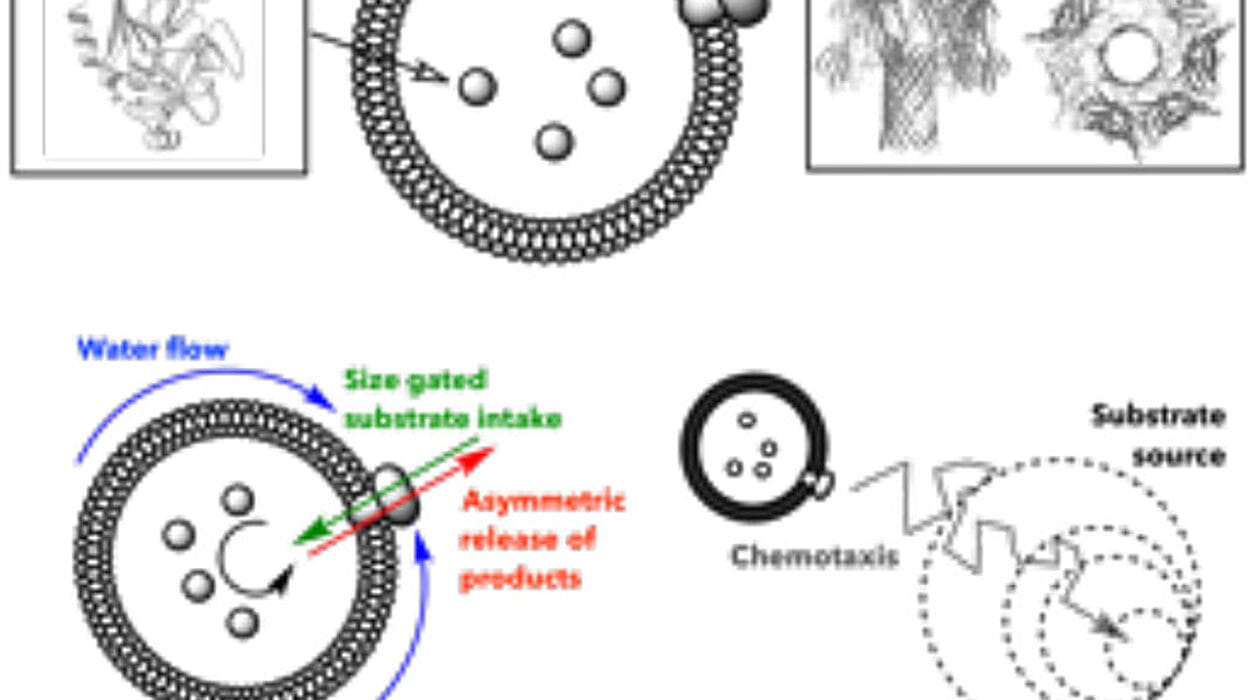

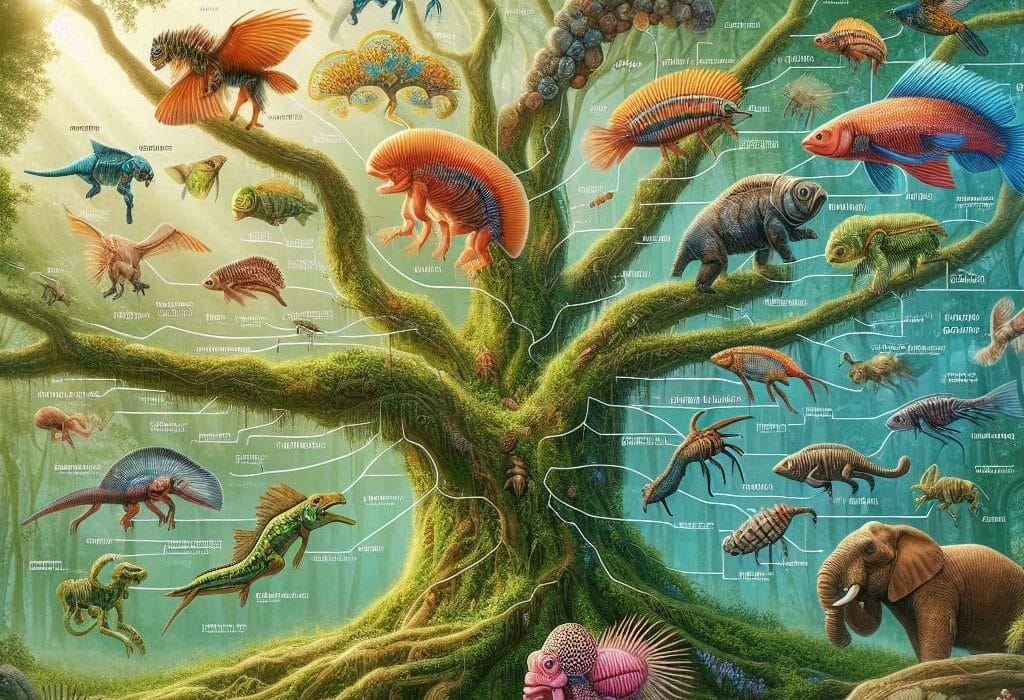

The core insight was simple yet profound: species change over time. They evolve. And the engine of that evolution is natural selection—the differential survival and reproduction of individuals with favorable traits. Over many generations, small changes accumulate, leading to the emergence of new species. Nature, not divine intervention, sculpts life.

But this idea clashed violently with Victorian religious doctrine. The prevailing view held that God had created all species in their present form, each perfectly adapted and immutable. To suggest that humans shared a common ancestor with apes, or that natural processes could account for life’s complexity, was scandalous.

Darwin knew this. He also knew he needed overwhelming evidence.

Years of Relentless Investigation

For nearly twenty years, Darwin quietly amassed data. He bred pigeons, studied barnacles, examined the fossil record, and pored over plant and animal classifications. He corresponded with naturalists around the globe. Every scrap of evidence was examined and re-examined. He wanted no gaps, no weak points. His house in Down, Kent, became a fortress of thought and observation.

He also suffered. Plagued by chronic illness—headaches, stomach issues, nausea, possibly triggered by stress—Darwin lived a secluded, often reclusive life. But the work drove him on. He filled notebook after notebook with his growing body of proof.

Still, he hesitated. To publish his theory would mean professional controversy, theological outrage, and possibly the ruin of his reputation. Then, in 1858, something extraordinary happened: he received a letter from a young naturalist named Alfred Russel Wallace. Wallace, working in the Malay Archipelago, had independently arrived at the same theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin was stunned.

Rather than fall into rivalry, Darwin and Wallace presented their ideas jointly to the Linnean Society in 1858. A year later, Darwin published the book that would change everything.

On the Origin of Species: A Bombshell in Print

On November 24, 1859, Darwin released his masterpiece: On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. The first edition of 1,250 copies sold out immediately.

The book was dense with evidence but written in clear, compelling prose. Darwin laid out his argument methodically, drawing from geology, embryology, animal breeding, and biogeography. He avoided direct discussion of human evolution—saving that bombshell for later—but readers understood the implications. If all species evolved by natural laws, then so did humans.

Reaction was swift and fierce. Some scientists hailed the book as a triumph. Others denounced it as heresy. Theologians called it a threat to morality and faith. But the public was fascinated. Debates raged in lecture halls, newspapers, and dinner parties.

Darwin had not just introduced a theory. He had launched a new worldview, one in which nature was dynamic, life was interconnected, and humanity was not the center of creation but a part of it.

The Evolution of a Legacy

Darwin continued writing for the rest of his life. He expanded his arguments in The Descent of Man, published in 1871, where he directly tackled human evolution. He explained that humans shared ancestry with other primates and that sexual selection played a role in shaping traits like intelligence, creativity, and even beauty.

He also published detailed studies on orchids, insectivorous plants, earthworms, and expression of emotions in animals and humans. He was a man obsessed not with grandeur but with detail—uncovering the small mechanisms that drove life’s great transformations.

Despite the controversy, Darwin earned widespread respect. He never claimed to be a prophet, only a scientist seeking truth. He was modest, careful, and self-questioning. He listened to critics and revised his views when warranted. He died on April 19, 1882, at age 73, and was buried in Westminster Abbey, an extraordinary honor for a man whose work had once been seen as blasphemous.

The World After Darwin

Darwin’s theory shook the foundations of science, religion, and philosophy. It redefined biology as a historical science, where the past shaped the present and patterns could be explained by cause and effect. It provided a unifying framework that made sense of the diversity of life, the fossil record, and the distribution of species.

But it also forced humanity to confront its own origins. We were not separate from nature, but a part of it. The boundary between human and animal, sacred and profane, creator and creature, was forever blurred.

Over the decades, Darwin’s ideas were tested, challenged, and refined. Genetics, unknown in Darwin’s time, eventually provided the missing mechanism of inheritance. The discovery of DNA, the rise of molecular biology, and advances in paleontology all confirmed and extended Darwinian principles. Today, evolution by natural selection is the foundation of modern biology.

Yet Darwin’s impact goes beyond science. His theory transformed how we see ourselves. It invited humility. It made us wonder not just what we are, but where we came from, and how the slow, blind dance of nature could produce such beauty, complexity, and consciousness.

The Man Behind the Revolution

Charles Darwin was not a warrior or a crusader. He was a man of caution and compassion, of sickness and silence. He was deeply devoted to his wife Emma, who remained a believer even as his doubts grew. He struggled with the moral implications of his work, the suffering it might cause, and the discomfort it brought to his religious family and friends.

But he never abandoned truth. He believed that truth—carefully sought, honestly examined—was a moral good. In his quiet way, he reshaped not just a discipline, but the very way human beings understand their place in the cosmos.

His life was not a straight path of genius, but a winding journey of observation, thought, doubt, and discovery. He began as a child marveling at beetles and ended as an old man who had cracked one of nature’s deepest mysteries.

Darwin changed the world not with a war or a government or an invention, but with an idea: that life changes, that nature selects, and that we are all kin—every creature, every leaf, every fossilized bone.

It is an idea that continues to inspire wonder, stir controversy, and illuminate the mystery of life itself.