In the arid northeast of Brazil, far from the crashing waves of the Atlantic and deep within the sunbaked landscapes of the Araripe Basin, lies a window into prehistory. This region, known as the Santana Group, has long been one of the world’s most remarkable fossil sites—a time capsule preserving the life and death of creatures that once ruled the skies and seas of the Cretaceous period, around 110 million years ago.

For decades, this site has yielded exquisite fossils of fish, plants, and above all, pterosaurs—the flying reptiles that dominated prehistoric skies. These delicate, winged creatures are among the most iconic symbols of the age of dinosaurs. Yet, just when paleontologists thought the Santana Group had given up all its biggest secrets, a new study published in Scientific Reports has revealed something extraordinary: a previously unknown filter-feeding pterosaur species, discovered not in a fresh dig, but inside a fossilized mass of dinosaur vomit.

The Fossil Hidden in Plain Sight

It’s not every day that a groundbreaking scientific discovery begins in the back room of a museum. The fossil that would rewrite a small chapter of prehistory had actually been sitting unnoticed for years in the collections of the Museu Câmara Cascudo (MCC) at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN).

It wasn’t even recognized for what it truly was. The specimen had little accompanying information—no excavation date, no precise origin within the Santana Group—and it appeared, at first glance, to be an unremarkable collection of bones and debris embedded in limestone.

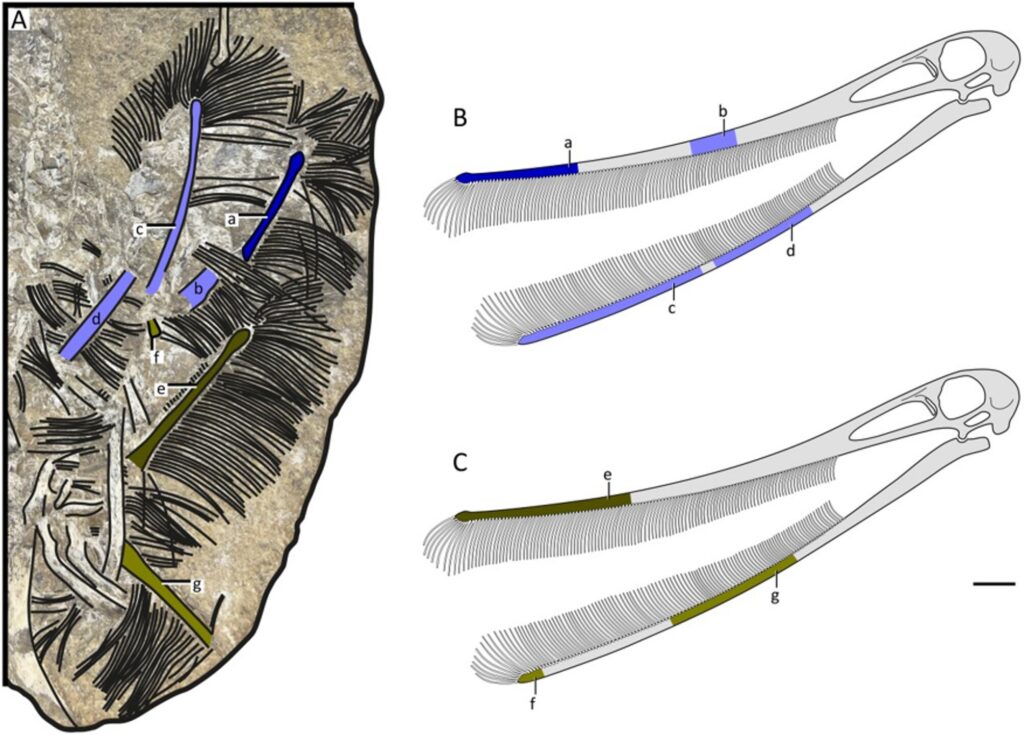

But when researchers took a closer look, they realized they were staring at something astonishing: the fossilized remains of a predator’s last meal. The jumble of bones, fish remains, and fractured fragments of pterosaur skeletons were encased together in what scientists call a “regurgitalite”—a polite term for fossilized vomit.

Within this prehistoric pellet lay the partial remains of two individuals of a completely new pterosaur species, along with four small fish. The bones were crushed and fragmented, a telltale sign of having been swallowed and regurgitated by a larger predator millions of years ago.

“Fracturing of the pterosaur bones most likely occurred during ingestion, as a result of mechanical processing by the predator,” the study’s authors explain. The soft tissues had long since been digested, leaving behind the harder fragments that fossilized together.

What had once been discarded by a predator 100 million years ago had become a priceless key to understanding pterosaur evolution.

The Birth of Bakiribu waridza

The team named the new species Bakiribu waridza—a tribute to the Indigenous Tupi language, meaning roughly “the one that filters.” The name reflects both the creature’s unique feeding strategy and its place of discovery in Brazil’s ancient basin

Bakiribu was a member of the Ctenochasmatidae, a family of pterosaurs known for their elongated snouts and densely packed, comb-like teeth used for filtering food from water—much like modern flamingos or baleen whales. But what made Bakiribu special was its position in the evolutionary tree.

Through detailed phylogenetic and paleohistological analysis, researchers determined that Bakiribu was closely related to another filter-feeder, Pterodaustro, previously discovered in Argentina. Yet Bakiribu’s teeth and jaw structure were different enough to suggest that it bridged a critical evolutionary gap between older, more primitive filter-feeding pterosaurs like Ctenochasma and more derived species like Pterodaustro.

According to the authors, “Bakiribu is intermediate between Ctenochasma and Pterodaustro, thus partially bridging a key evolutionary gap within Ctenochasmatinae.”

This discovery fills an important missing link in the evolutionary story of these fascinating creatures, helping scientists understand how filter-feeding evolved in flying reptiles and how different species adapted to distinct ecological niches across ancient South America.

The Predator’s Shadow

The discovery of Bakiribu inside fossilized vomit not only revealed a new species—it also opened a rare window into the ancient food chains of the Cretaceous ecosystem.

The fossil showed that these delicate flying reptiles were not just sky-dwellers; they were also part of a dynamic web of life and death that connected air, land, and water. The presence of both pterosaur and fish remains in the regurgitalite suggests that the predator—most likely a large, fish-eating dinosaur—had a varied diet and powerful digestive processes capable of breaking fragile bones.

Among the prime suspects are the spinosaurids, a family of semi-aquatic, crocodile-snouted dinosaurs that prowled the region’s rivers and lagoons. Spinosaurids are already known to have fed on both fish and pterosaurs, as evidenced by a previously discovered spinosaurid tooth embedded in a pterosaur neck vertebra from the same geological formation.

Another possibility is that a large ornithocheiriform pterosaur may have preyed on smaller species like Bakiribu. These flying giants, with wingspans reaching up to six meters, were formidable hunters in their own right.

Whatever the culprit, the regurgitalite captures a frozen moment of Cretaceous predation—a direct, physical record of the relationship between hunter and hunted.

A Snapshot of Prehistoric Life

Beyond its shock value, the discovery of Bakiribu waridza paints a vivid picture of life in Brazil’s Cretaceous wetlands. Around 110 million years ago, the Araripe Basin was a lush coastal ecosystem filled with shallow lagoons and rivers teeming with fish, insects, and other aquatic creatures. It was a world of abundance, where flying reptiles skimmed the water’s surface, snapping up small prey with their comb-like teeth.

In that thriving environment, Bakiribu would have been an elegant, long-snouted pterosaur, gliding above the water on leathery wings, filtering plankton or tiny crustaceans from the shallows. Its specialized feeding adaptations reveal an ecosystem rich and complex enough to support a diversity of dietary niches—a snapshot of evolution in motion.

The fossil also provides a reminder that even in prehistory, nature wasted nothing. What one creature could not digest became a record for another era—a scientific gift preserved through deep time.

Forgotten Fossils, New Discoveries

One of the most remarkable aspects of this study is not just the discovery itself, but how it happened. The fossil wasn’t freshly excavated or unearthed through modern technology. It was already in a museum drawer, quietly waiting to be recognized.

The authors emphasize the importance of revisiting old collections, noting that museum archives around the world are filled with overlooked or misidentified specimens that may hold answers to big evolutionary questions.

As they write, “The significance of understudied, long-held museum specimens for revealing key evolutionary and paleoecological insights cannot be overstated.”

In other words, the past still speaks—if we know where to listen.

The Legacy of Bakiribu

The discovery of Bakiribu waridza is more than a scientific footnote—it’s a story of patience, curiosity, and the hidden power of forgotten fossils. From a mass of fossilized vomit emerged a new species, a new evolutionary connection, and a richer understanding of prehistoric Brazil.

It reminds us that evolution is not a straight line but a vast and intricate web. Every fossil, every fragment, every clue—no matter how humble—can reshape our understanding of life’s history.

Somewhere, deep beneath the sunlit cliffs of the Santana Group, more secrets are still buried. And perhaps, in another quiet museum collection, the next great discovery is already waiting—hidden in stone, waiting for science to see it anew.

More information: R. V. Pêgas et al, A regurgitalite reveals a new filter-feeding pterosaur from the Santana Group, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-22983-3