It’s easy to forget that we are animals. Despite the cities we build, the space stations we orbit, the symphonies we compose, and the AI we now teach to think, humans are just one twig on the vast, tangled tree of life. But how did this twig rise so high? How did we—Homo sapiens—emerge from the ancient soil of time, not merely as another primate, but as the only one to send rockets to the stars?

The story of human evolution is not a straight line. It is not the march of progress from ape to man, as old cartoons liked to suggest. It is a winding path filled with dead ends, dramatic shifts, strange cousins, and unexpected leaps. It is a story billions of years in the making—slow, violent, beautiful, and often tragic. It’s also a story still being written.

To understand where we came from, we must travel back—far beyond history, beyond even memory, into a world without humans at all.

The Deepest Roots of Life

Life on Earth began at least 3.5 billion years ago, perhaps even earlier, in a world utterly alien to our own. There were no trees, no animals, no oxygen-rich air—only oceans and volcanic landscapes, simmering with the building blocks of biology.

From this ancient broth, the first simple cells—prokaryotes—emerged. They were tiny, single-celled, and unimaginably ancient. For over two billion years, life remained microscopic. Then something revolutionary occurred: some cells learned to cooperate, forming complex, eukaryotic organisms with internal structures and specialized functions. These were our ancestors in the most distant sense.

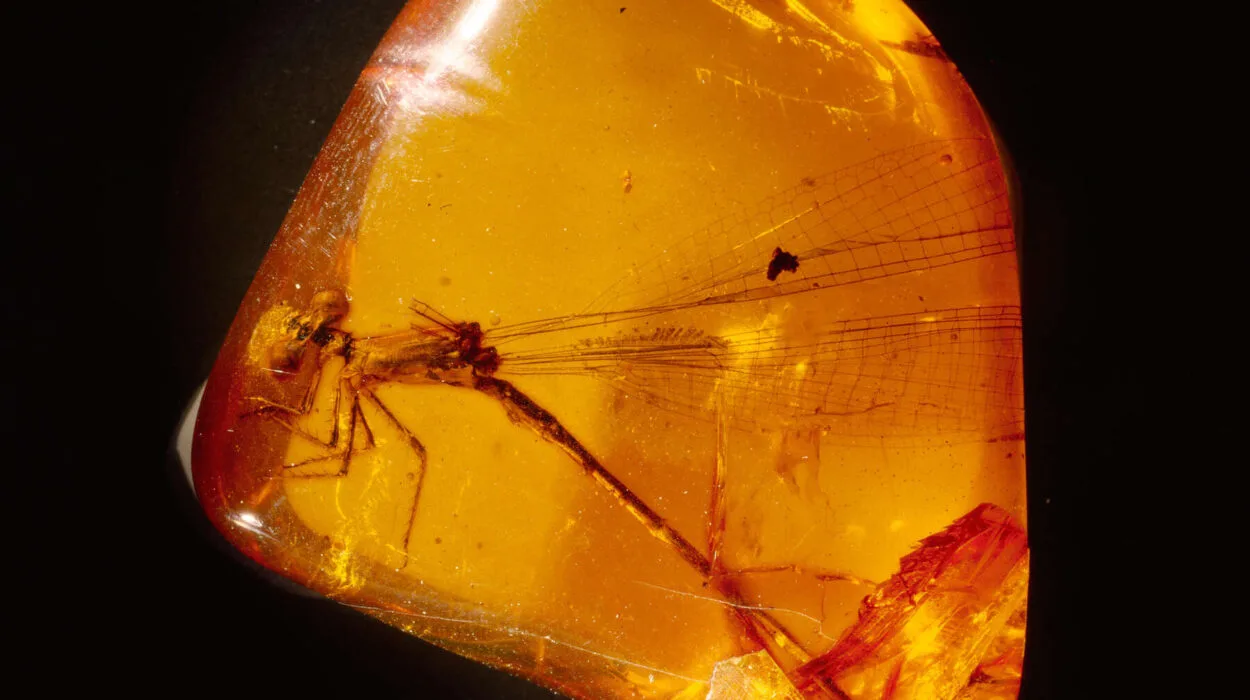

Multicellular life exploded in diversity. Plants, fungi, and animals arose. Some crawled onto land. Others stayed in the sea. Over millions of years, vertebrates evolved spines, fish evolved limbs, and some creatures began to breathe air. Among them, the mammals would eventually take center stage—but only after catastrophe.

When the Dinosaurs Died, Mammals Rose

About 66 million years ago, a space rock roughly the size of a city struck Earth near what is now Mexico. The impact was cataclysmic. The skies turned black. Plants died. Food chains collapsed. In the mass extinction that followed, the age of dinosaurs came to a fiery end. Nearly 75% of all species were wiped out.

But out of that disaster came opportunity. Small, warm-blooded mammals, once hiding in the shadows of the giants, now had space to evolve and diversify. Over tens of millions of years, some of these mammals returned to the sea and became whales. Others took to the skies as bats. Still others stayed on land, becoming hooved runners, gnawing rodents, and sharp-toothed predators.

Among them was a lineage of creatures living in trees, with grasping hands, good vision, and complex social lives. These were the primates—our ancient relatives.

The Rise of the Primates

Primates evolved roughly 60 million years ago, likely beginning as small, insect-eating creatures that scampered through tropical forests. Over time, they developed traits that would come to define the group: forward-facing eyes for depth perception, flexible hands for gripping branches, and large brains relative to body size for navigating complex environments.

As millions of years passed, primates split into two major groups. One included lemurs and lorises, mostly found today in Madagascar. The other group—anthropoids—included monkeys, apes, and eventually, humans.

From the anthropoids came the great apes, or hominids—orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and us. These animals didn’t just survive by brute strength. They built relationships, used tools, mourned their dead, and even recognized themselves in mirrors. But only one lineage would take the leap to language, art, and spaceflight.

That leap would take place in Africa.

The African Crucible

Some six to seven million years ago, in the forests and savannas of central and eastern Africa, a population of ape-like creatures began to change. These were not yet humans, but they were not quite apes either. They walked upright, at least part of the time. Their brains were small, but their hands were nimble. They lived in groups and probably communicated with rudimentary vocalizations.

They were the hominins—the direct ancestors and close relatives of humans. Fossils like Sahelanthropus tchadensis, Orrorin tugenensis, and Ardipithecus ramidus offer tantalizing glimpses into this mysterious period. These creatures walked upright before they had big brains. Walking on two legs—bipedalism—was one of the first major changes in our lineage. But why did it happen?

Perhaps standing up freed the hands for carrying food or infants. Maybe it helped in seeing over tall grass or regulating body temperature in the hot African sun. Whatever the reason, bipedalism was a defining step on the road to humanity.

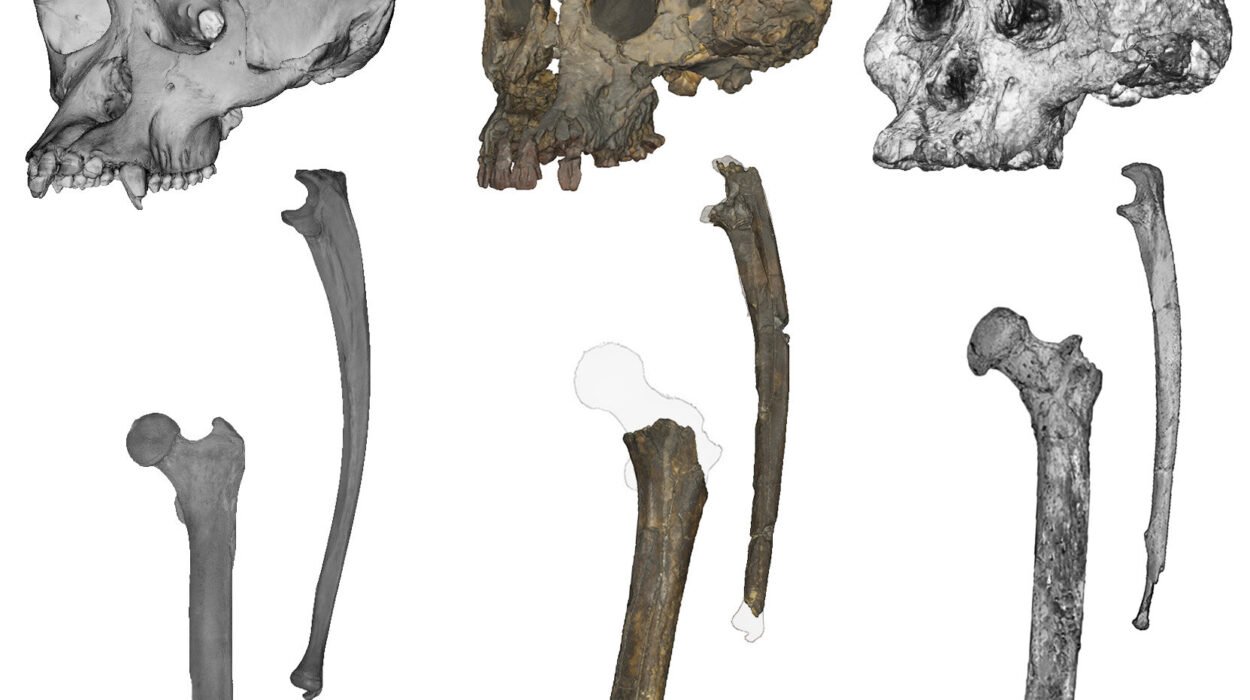

Australopithecus: The First Truly Upright Ancestors

Around 4 million years ago, a new genus emerged: Australopithecus. These hominins were fully bipedal, with strong legs and humanlike feet, but they still had long arms and curved fingers—hints of their tree-dwelling past. They lived in diverse environments and likely used simple tools, though no stone artifacts are directly linked to them.

One of the most famous members of this group is “Lucy,” a 3.2-million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis discovered in Ethiopia. Her skeleton revealed the graceful blend of primitive and advanced traits that marked this stage of evolution.

These beings were survivors—clever, adaptive, and social. But they were not yet builders of civilizations. That would come later, with a bold leap: the evolution of a larger brain.

The Birth of the Genus Homo

Some 2.5 million years ago, climate change began to reshape Africa’s landscape, turning lush forests into open savannas. Hominins that could think quickly, learn socially, and adapt behaviorally had an advantage.

From these pressures, a new kind of creature emerged: Homo habilis, the first species in the genus Homo—our own group. Their name means “handy man,” because they left behind clear evidence of stone tools. With these tools, they could butcher meat, crack bones for marrow, and alter their environment in ways no creature had before.

Their brains were larger than those of Australopithecines, and their faces more humanlike. They were learning not just to survive, but to manipulate the world intentionally.

Homo Erectus: The First Global Wanderers

Around 1.9 million years ago, a new species evolved—Homo erectus. They were taller, stronger, and smarter than their predecessors. They made better tools, controlled fire, and most remarkably, they left Africa.

Homo erectus spread across Eurasia, from Indonesia to Georgia to China. They adapted to cold, to deserts, to forests. They hunted in groups, cared for each other, and lived in structured communities. They survived for over a million years, making them one of the longest-lasting human species ever.

In many ways, they were already human in mind and body. But they were not us. The final steps toward modernity still lay ahead—and they would take many different forms.

A Tangled Family Tree

For a long time, scientists imagined human evolution as a ladder: a straight progression from primitive to advanced. But reality is far messier. It’s more like a bush, or a river delta, with many branches—some ending in extinction, others merging, diverging, or running parallel.

In the past few decades, we’ve discovered a dazzling variety of ancient human relatives. There was Homo heidelbergensis, a likely ancestor to both Neanderthals and us. There was Homo naledi, with a strange mix of ancient and modern features. There was Homo floresiensis—the “hobbit” of Indonesia, barely over a meter tall. And in Siberia, the Denisovans left behind DNA but almost no fossils.

These species overlapped in time and space. Some interbred. Others vanished. Evolution did not favor a single path—it explored many.

And then, about 300,000 years ago, in Africa, Homo sapiens appeared.

The Dawn of Us

Early Homo sapiens were not dramatically different from their cousins. They made tools, hunted game, and lived in small bands. But over time, something changed. Perhaps it was the emergence of complex language—not just grunts and calls, but grammar, metaphor, storytelling. Perhaps it was the development of symbolic thought, as shown in cave paintings, beads, and burial rituals. Perhaps it was cultural evolution—the ability to pass on knowledge through generations, to build not just physically, but socially and intellectually.

Whatever the spark, it gave humans a unique advantage. We became not just smart, but self-aware. We asked questions. We invented gods. We made music. We remembered the dead.

Around 60,000 years ago, small bands of Homo sapiens began leaving Africa, spreading into the Middle East, Asia, Australia, and Europe. Along the way, they encountered other humans—Neanderthals, Denisovans—and sometimes, they mingled. Today, many people carry small amounts of Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA. These were not alien others. They were kin.

But only Homo sapiens survived.

Why Did We Survive When Others Did Not?

This remains one of the great mysteries. Neanderthals were intelligent, tool-using, fire-controlling humans with large brains. Denisovans were similarly advanced. Why did they vanish while we thrived?

Perhaps climate change pushed their populations past the point of recovery. Perhaps competition with Homo sapiens for food, mates, and territory proved too much. Perhaps interbreeding led to their gradual absorption.

Or maybe, just maybe, the key was imagination—the ability to cooperate in larger groups through shared myths, beliefs, and goals. It was not just our biology that gave us an edge. It was our minds.

From Hunters to Farmers to Cities

For 95% of our history, humans lived as hunter-gatherers. We moved with the seasons, followed herds, gathered fruit, and lived in tune with nature’s rhythms. Our brains evolved in this context—tribal, mobile, communal.

But around 12,000 years ago, something extraordinary happened: we began to farm.

The Agricultural Revolution was not inevitable. It arose in scattered places—Mesopotamia, China, Mesoamerica, and others. People domesticated wheat, rice, corn, and animals. For the first time, humans could settle in one place, produce food surpluses, and grow large communities.

With farming came cities. With cities came governments, laws, religion, art, and war. Written language appeared. Civilizations rose and fell. Empires expanded. And always, behind it all, human evolution continued—not just biologically, but culturally, technologically, socially.

Are We Still Evolving?

It’s a common question: is human evolution still happening? The answer is yes—but not in the way it once did.

In the past, evolution was driven by natural selection—survival and reproduction in response to the environment. Today, medicine, technology, and global society have changed those rules. We no longer evolve just to survive lions or plagues.

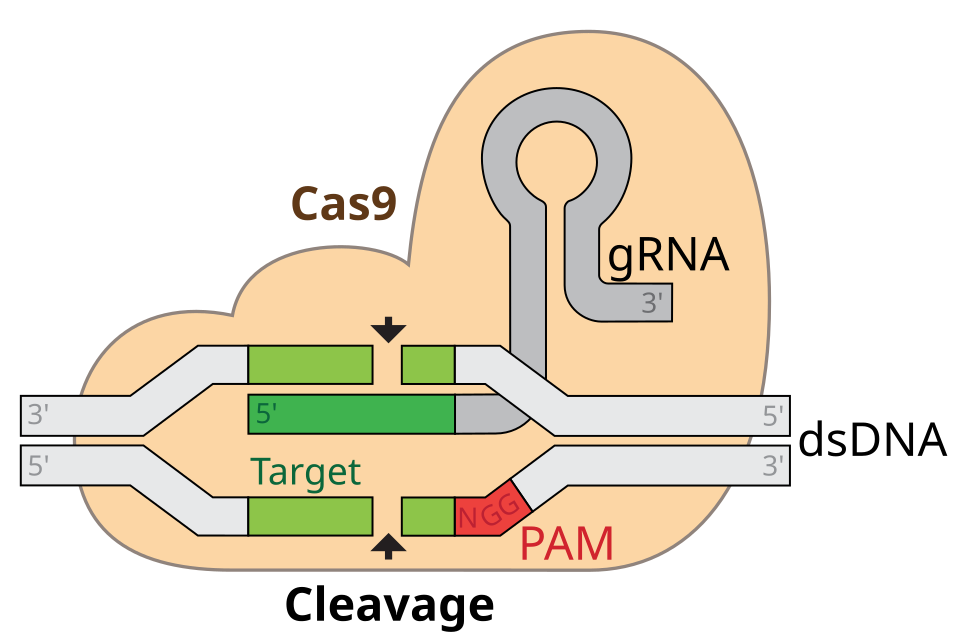

But evolution is not just about hardship. It’s about change in gene frequencies over time. And that is still happening. Genes related to disease resistance, metabolism, high-altitude adaptation, and even brain function continue to shift. And our culture now evolves faster than our genes.

We’ve entered a new era—an age where we may direct our own evolution through genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology. Whether this leads to harmony or hubris remains to be seen.

The Story That Never Ends

The story of human evolution is not just a tale of fossils and DNA. It is the story of who we are, where we came from, and what we might become.

We are the product of ancient stars and ancient apes. We are born of dust and dreams, blood and stardust, chance and choice. No other species on Earth tells stories about itself. No other creature wonders where it came from. No other animal asks what it means to be conscious, or where the universe is going.

We are alone, but not isolated. We are new, but rooted in the ancient. We are flawed, but capable of great beauty.

And our evolution is far from over.