In the vast architecture of the universe, most planets are creatures of routine. They circle their stars with dependable regularity, bound by gravity and illuminated by borrowed light. Yet some worlds live very different lives. They wander alone through interstellar space, untethered to any star, silent and dark. Astronomers call them free-floating or rogue planets, and until recently, they were among the most elusive objects in the cosmos.

A new discovery has changed that picture in a quiet but profound way. Astronomers have identified a rogue planet whose mass and distance from Earth could be measured directly, a rare achievement for an object that emits no light and keeps no stellar companion. The finding, reported in a study published in Science, emerged not from a single planned observation, but from a fortunate alignment of telescopes, timing, and geometry that briefly made the invisible measurable.

Why Rogue Planets Almost Never Reveal Themselves

Finding a planet usually means watching its star. Astronomers have grown adept at reading the subtle signals planets imprint on the light of their hosts. When a planet crosses in front of a star, the star’s light dims slightly and rhythmically. When a planet tugs gravitationally on its star, the star wobbles ever so gently. These techniques have revealed thousands of extrasolar planets, but they all depend on the same essential ingredient: a visible star.

Rogue planets offer no such convenience. Without a host star, they cannot cause a transit or a wobble. They also do not shine on their own. Compared to stars, planets are cold and faint, effectively invisible against the darkness of space. A rogue planet drifting between stars is, in most circumstances, undetectable.

The only reliable way astronomers have found to detect these lonely objects is through a phenomenon known as microlensing. This effect relies not on the planet’s light, but on its gravity. When a massive object passes in front of a distant background star, its gravity bends the star’s light, causing the star to appear briefly brighter to observers on Earth. The light behaves as though a cosmic lens has passed across it, magnifying the star for a short time before the effect fades.

Microlensing events are fleeting and rare, but they offer a unique opportunity. In principle, the way the light is magnified contains information about the mass of the object doing the lensing. In practice, however, there is a major obstacle.

The Puzzle of Mass and Distance

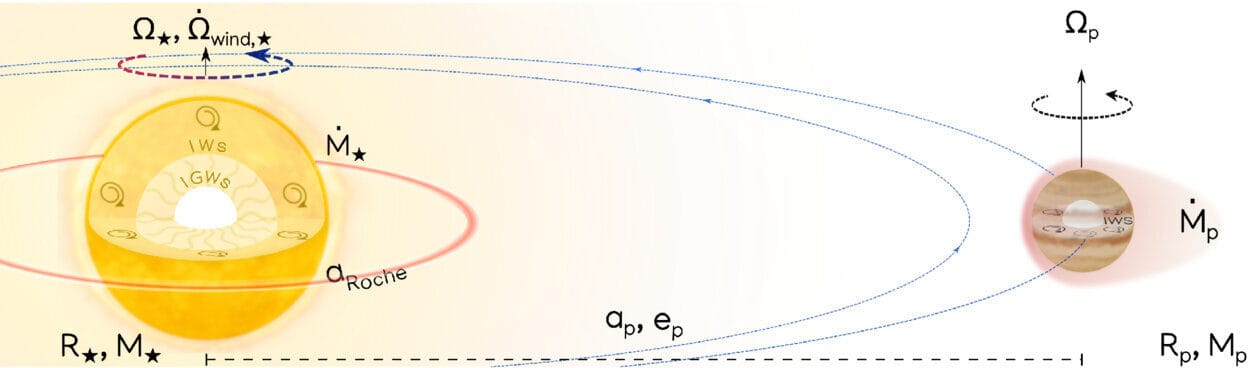

The challenge astronomers face when interpreting microlensing events is known as mass-distance degeneracy. The shape of a microlensing light curve can be produced by different combinations of mass and distance. A closer, lighter object can bend light in a way that looks remarkably similar to a heavier object that is farther away. Without knowing how distant the lensing object is, astronomers cannot pin down its mass with certainty.

As a result, most previously detected rogue planets have come with large uncertainties. Researchers could estimate whether an object was roughly planetary in mass or more likely a brown dwarf, but exact values remained out of reach. The lonely nature of these planets seemed to condemn them to permanent ambiguity.

Then, for one brief event, the geometry of the universe intervened.

A Moment of Perfect Alignment

The microlensing signal of this newly identified rogue planet was first noticed by multiple telescopes on Earth. Independently, it was also observed by Gaia, a space-based telescope that orbits far from Earth’s surface. Because two research groups detected and analyzed the event, the planet received two names: KMT-2024-BLG-0792 and OGLE-2024-BLG-0516.

What set this event apart was not just the number of telescopes involved, but where they were located. Observing the same microlensing event from different positions in space allows astronomers to detect slight differences in timing and brightness. These differences can be used to calculate microlensing parallax, which reveals the distance to the lensing object.

In this case, Gaia happened to be in exactly the right place at exactly the right time.

“Serendipitously, the KMT-2024-BLG-0792/OGLE-2024-BLG-0516 microlensing event was located nearly perpendicular to the direction of Gaia’s precession axis. This rare geometry caused the event to be observed by Gaia six times over a 16-hour period, beginning close to peak magnification,” the study authors write.

Those six observations, spread across the critical hours of the event, provided just enough information to break the mass-distance degeneracy. For once, the numbers could settle into place.

A Lonely World Takes Shape

With the distance now measurable, the researchers could determine the planet’s mass directly. The results revealed a world that is substantial, but not enormous. The planet has a mass of about 22 percent that of Jupiter, placing it just under the mass of Saturn.

Its distance from Earth is equally striking. The planet lies around 3,000 parsecs away, or just under 10,000 light years, deep within the Milky Way. During the microlensing event, it passed in front of a red giant star, whose light briefly betrayed the presence of the otherwise unseen planet.

For a brief moment, a solitary object wandering through interstellar space announced itself across thousands of light years. Then, as microlensing events always do, the signal faded, and the planet returned to darkness.

The Mysterious Gap Called the Einstein Desert

This discovery carries weight not just because of what was measured, but because of where the planet falls in a broader pattern. Previous microlensing surveys have hinted at a gap in the distribution of free-floating objects, a region known as the Einstein desert. This gap appears to separate typical planets from brown dwarfs, which are objects too massive to be planets but not massive enough to ignite as stars.

Most previously identified rogue planets were thought to have masses below that of Jupiter. Researchers interpreted this as evidence that these planets formed in protoplanetary disks around stars and were later ejected through gravitational interactions. More massive objects, by contrast, are less likely to be flung out of planetary systems and more likely to form in isolation as brown dwarfs.

The newly measured planet sits near a critical boundary. Its mass is large for a planet, yet clearly below the range expected for brown dwarfs. Its very existence, drifting freely through space, provides a concrete data point in a region that was previously defined mostly by statistical inference.

Violence at the Birthplace of Planets

The study’s authors place this finding within a larger narrative about how planetary systems evolve and sometimes unravel. They note that earlier microlensing events lacked direct mass measurements, but statistical analyses suggested that most free-floating planets are relatively small.

“Although previous free-floating planet (FFP) events did not have directly measured masses, statistical estimates indicate that they are predominantly sub-Neptune mass objects, either gravitationally unbound or on very wide orbits.

“Such objects can be produced by strong gravitational interactions within their birth planetary systems. We conclude that violent dynamical processes shape the demographics of planetary-mass objects, both those that remain bound to their host stars and those that are expelled to become free floating.”

In this view, rogue planets are not cosmic accidents, but survivors of upheaval. They are worlds that formed alongside others, only to be cast out by gravitational chaos. The mass of this newly measured planet suggests that even relatively large planets can be expelled under the right conditions, though such events may be rarer.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it transforms an abstract population into tangible worlds. Rogue planets have long been discussed as statistical possibilities, inferred from brief flashes of light and uncertain models. By directly measuring both mass and distance, this study demonstrates that these objects can be characterized with the same physical rigor as planets bound to stars.

The discovery also shows the power of combining ground-based and space-based observations. A single telescope, or even a network on Earth, would not have been enough. Only by viewing the same event from different vantage points could astronomers resolve the ambiguity that has long plagued microlensing studies.

Most importantly, this finding deepens our understanding of planetary systems as dynamic, sometimes violent environments. The quiet regularity of planetary orbits can hide a turbulent past, one in which worlds are scattered and lost. Each rogue planet detected and measured adds a chapter to that story, revealing not just how planets live, but how they are sometimes forced to wander alone through the galaxy.

In the fleeting brightening of a distant star, astronomers have glimpsed a planet without a home, and in doing so, have illuminated the unseen forces that shape planetary destinies across the universe.

More information: Subo Dong et al, A free-floating-planet microlensing event caused by a Saturn-mass object, Science (2026). DOI: 10.1126/science.adv9266

Gavin A. L. Coleman, Two views of a rogue planet, Science (2026). DOI: 10.1126/science.aed5209