In the far north of Japan, where land meets cold seas and layers of ancient sediment lie quietly beneath the surface, a discovery waited patiently for millions of years. It was not large. It did not glitter. It could not be seen without careful work and powerful magnification. Yet when scientists finally noticed it, this tiny fossil carried with it a sweeping story about the movement of oceans, the warmth of the planet, and the hidden connections that once linked distant corners of the Pacific.

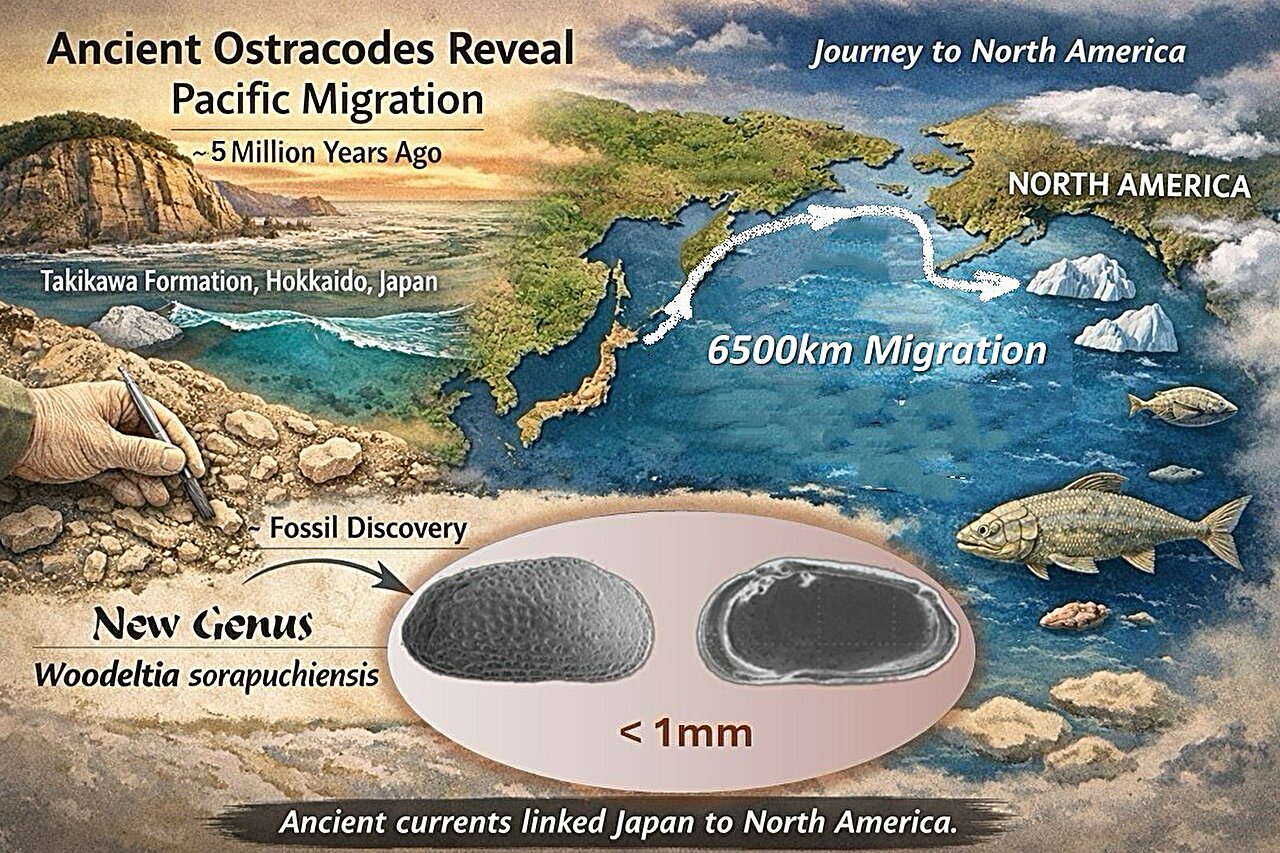

A research team led by scientists at Kumamoto University has uncovered a new genus of microscopic crustaceans preserved in rock from Hokkaido. These fossils, no more than a few millimeters in size, belong to ostracods—shrimp-like creatures sealed inside hard shells. By studying them closely, the team identified something entirely new and named it Woodeltia. What began as a careful examination of minute shapes soon grew into a window onto a time when Earth’s oceans behaved very differently from today.

Meeting the Tiny Witnesses of an Ancient Sea

Ostracods are easy to overlook. They are small, enclosed in shells, and live quiet lives on or near the seafloor. But for paleontologists, they are among the most eloquent storytellers of the past. Each species has its own preferences for temperature, depth, and environment. When ostracods die, their shells can fossilize, locking those preferences into stone.

The fossils studied by the Kumamoto University team came from the Takikawa Formation in Hokkaido, a sedimentary layer formed during the Early Pliocene, around three to four million years ago. This was a world warmer than today, a planet where seas carried different currents and coastlines felt different climates. Within these sediments, the researchers found ostracods unlike any previously described.

By carefully examining their shapes and comparing them with known species, the team realized they were looking at a new genus. They named it Woodeltia, adding a fresh branch to the tree of life preserved in the fossil record. The discovery was later published in the Journal of Paleontology, formally introducing Woodeltia to the scientific world.

A Name That Bridges Oceans

What made Woodeltia especially intriguing was not just that it was new, but who its closest relatives appeared to be. The genus showed a close relationship to ostracod species previously known only from distant regions of the North Pacific. This was unexpected. The fossils were found in northern Japan, yet their nearest known kin lived far away.

This connection suggested something remarkable. During the Early Pliocene, marine organisms like ostracods were not confined to isolated regions. Instead, they could migrate across vast oceanic areas. For creatures so small, such journeys would have depended entirely on the movement of water itself.

The implication was clear: ocean currents in the North Pacific must have been actively linking these distant regions. The sea was not a series of disconnected basins but a dynamic, flowing system capable of transporting life across great distances.

Following the Currents of a Warmer World

The Early Pliocene is a period that draws particular attention from climate scientists. It represents a time when global temperatures were higher than today, and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were similar to those projected for the coming decades. Studying this era is like reading a preview of possible futures.

In this warmer world, oceans played a crucial role in redistributing heat and nutrients. The discovery of Woodeltia adds a biological dimension to this picture. The presence of related species across distant parts of the North Pacific suggests that circulation patterns were already well developed and possibly more dynamic than previously believed.

Associate Professor Gengo Tanaka from the Center for Water Cycle, Marine Environmental and Disaster Management at Kumamoto University captured this idea directly when he said, “Our findings indicate that ocean circulation patterns in the North Pacific were more dynamic than previously thought. These tiny fossils provide direct biological evidence that marine pathways linking the northern Pacific regions were already active several million years ago.”

In other words, Woodeltia is more than a fossil. It is a traveler’s record, a biological trace of ancient currents that once carried life across an interconnected ocean.

The Takikawa Formation Keeps Speaking

The Takikawa Formation has long been known as a treasure trove of marine fossils. Layer by layer, it preserves snapshots of ancient seas that once covered northern Japan. Fish, mollusks, and microscopic organisms have all been found there, painting a rich picture of past marine ecosystems.

Yet the discovery of Woodeltia shows that even well-studied formations can still surprise scientists. Hidden among familiar fossils, entirely new species and even new genera can remain unnoticed until someone looks closely enough. Each new find deepens our understanding, adding nuance and detail to the story of Earth’s environmental history.

In this case, the value of the Takikawa Formation extends beyond local geology. The fossils it holds are pieces of a much larger puzzle, one that spans the entire North Pacific and reaches into questions about global climate and ocean behavior.

How the Small Reveals the Vast

There is something poetic about the way this discovery works. Ostracods are among the smallest animals to leave a fossil record, yet they can reveal some of the largest processes shaping the planet. Their shells record the conditions of the water they lived in. Their distribution records the pathways of ancient currents. Their relationships to other species record connections between distant regions.

By studying Woodeltia, researchers were able to infer not only the existence of a new genus but also the movement of oceans millions of years ago. This is the power of detailed paleontological work. When scientists pay close attention to microscopic organisms, they can uncover evidence for sweeping changes in climate and circulation.

The research demonstrates that understanding Earth’s history does not always require massive fossils or dramatic geological events. Sometimes, the most important clues are measured in millimeters and require patience, precision, and imagination to interpret.

A Mirror Held Up to the Future

The Early Pliocene is often described as a natural analog for future climate scenarios. It offers a glimpse of how Earth’s systems function under warmer conditions. By studying how oceans behaved during this time, scientists hope to better predict how modern marine ecosystems might respond to ongoing climate change.

The discovery of Woodeltia contributes directly to this effort. If ocean circulation patterns were already dynamic and interconnected during a warm period millions of years ago, this has implications for how heat, nutrients, and organisms might move through today’s oceans as the climate changes. It suggests that biological responses to warming can include large-scale migrations, reshaping ecosystems across entire ocean basins.

This does not provide simple answers or predictions, but it adds an important piece of evidence. It reminds researchers that oceans are not static and that life within them is closely tied to the movement of water on a planetary scale.

Why This Discovery Matters Now

At first glance, a new genus of microscopic crustaceans might seem like a small scientific footnote. In reality, it is a reminder of how deeply connected Earth’s systems are, and how much remains to be learned by looking carefully at the past.

Woodeltia matters because it provides direct biological evidence of ancient ocean circulation in the North Pacific. It matters because it strengthens the role of the Early Pliocene as a window into future climate conditions. It matters because it highlights the ongoing scientific value of Japan’s fossil-rich formations and the insights they continue to offer.

Most importantly, this research shows that understanding the future of our planet often begins with understanding its history at the smallest scales. Through the study of tiny fossils locked in stone, scientists can trace the movement of ancient seas and better grasp how oceans respond to a warming world. In doing so, they bring us closer to understanding not just where we have been, but where we may be headed.

More information: Kazumasa Mukai et al, Early Pliocene ostracodes from the Takikawa Formation in Hokkaido, northern Japan, and the new genus Woodeltia moving in the North Pacific Ocean, Journal of Paleontology (2025). DOI: 10.1017/jpa.2025.10178