There are few things more universal than touch. A hug from a parent. The soft nuzzle of a dog. The paw of a cat tapping your face as you sleep. From infancy, touch is how we first know love. It’s how we feel safe. It’s how we connect—without speaking a single word.

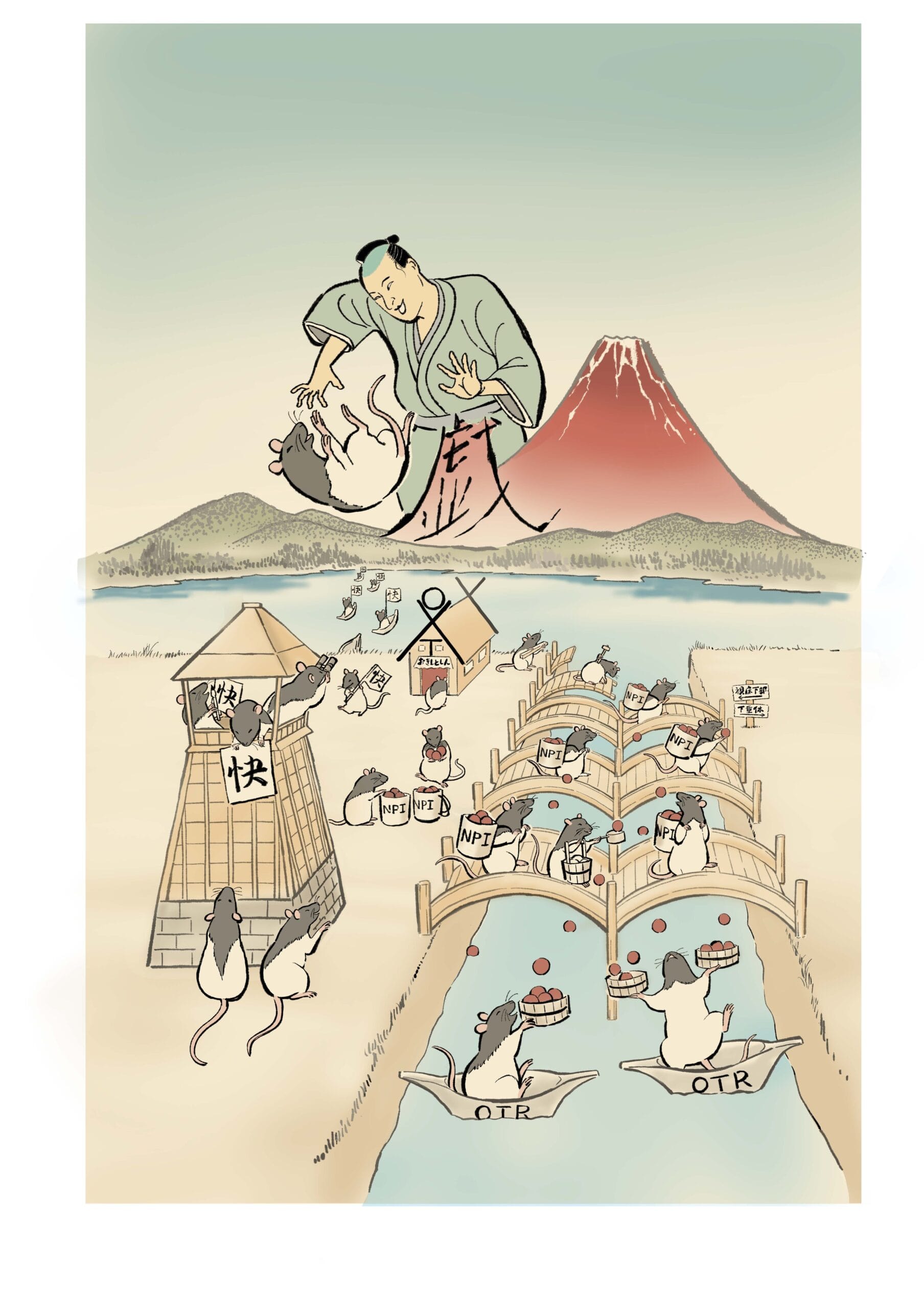

This simple, ancient language—one of skin against skin, warmth against warmth—is not unique to humans. In fact, touch is at the very core of how animals, especially mammals, build trust and social bonds. For young rats growing up in the world, rough-and-tumble play with their siblings is not just fun—it’s emotionally foundational. And new research now reveals something surprisingly tender about these tiny creatures: when you tickle a rat, it might just fall in love with you.

Laughter in the Shadows

It’s a strange idea, isn’t it? Tickling a rat. But in laboratories around the world, scientists have long known that rats emit ultrasonic “laughter” in the 50 kHz range—too high for human ears—when they play. This laughter is a sign of emotional pleasure. In the natural world, these sounds appear during joyful moments like wrestling, chasing, or exploring. But they can also be elicited by a human hand.

Yes, really. If you tickle a juvenile rat with your fingers, much like another rat might during play, the rat begins to emit high-pitched giggles—inaudible to us but unmistakably there. These giggles are more than a novelty; they are the echoes of something deeper. They are evidence of a cross-species emotional connection built not on shared language, but on touch.

Ten Days to Affection

Recently, in a study published on June 23, 2025, in the journal Current Biology, scientists at Okayama University in Japan took this strange little behavior seriously. Led by Dr. Himeka Hayashi, the research team set out to understand how something as simple as repeated tickling could build social attachment between rats and humans—and what that says about our ability to bond across species.

Their experiment was remarkably straightforward. For ten consecutive days, adolescent rats were gently tickled by human hands. At first, the rats were hesitant. They emitted only a few ultrasonic vocalizations, suggesting they weren’t yet enjoying the interaction. But by the fifth day, everything began to change. The laughter increased. By the tenth day, the rats were consistently giggling in response to tickling, an unmistakable sign that they were experiencing pleasure.

But the tickling did more than produce laughter. It shaped preference. In a follow-up test known as a conditioned place preference assessment—a behavioral assay that tests whether an animal prefers one environment over another—the rats showed a clear emotional attachment. They spent more time in the room where they had been tickled. Not because there was food there. Not because they were being rewarded in any other way. Simply because the memory of being touched with kindness had left a lasting impression.

The Brain Beneath the Bond

Beneath this laughter, however, lay something even more profound—a molecular signature of emotional transformation. Dr. Hayashi and her team looked into the rats’ brains to see what had changed.

They found that repeated tickling caused a notable increase in the expression of oxytocin receptors in a region of the brain called the ventrolateral part of the ventromedial hypothalamus, or VMHvl. This area of the brain, while small, plays a big role in social behavior and emotional processing.

Oxytocin is often called the “love hormone.” It’s released during affectionate touch, during childbirth and breastfeeding, and during moments of deep emotional connection. It fosters trust, reduces fear, and strengthens bonds. But until now, the exact neural pathways it uses to build connections between animals—especially animals and humans—have remained murky.

In this study, when researchers inhibited oxytocin signaling in the VMHvl, something remarkable happened. The rats’ affection for human hands disappeared. They no longer responded with the same joy. Their preference for the tickling room faded. It was as if the emotional glue holding the bond in place had dissolved.

This was more than a clue. It was a direct glimpse into the neurochemical machinery that allows two very different species—one wild, one human—to find comfort in each other’s touch.

Tracing Love’s Circuit

To take their investigation further, the scientists conducted a series of brain-tracing studies. These studies revealed that the oxytocin-responsive neurons in the VMHvl receive input from another part of the brain called the supraoptic nucleus. This region houses large, specialized cells called magnocellular neurons that produce oxytocin and project it across various brain areas.

These neural fibers connecting the supraoptic nucleus to the VMHvl suggest a dedicated circuitry through which oxytocin exerts its social magic. It’s not a vague, generalized effect—it’s targeted, coordinated, and deeply embedded in the brain’s design.

This discovery could reshape how we think about domestication, human-animal bonding, and even emotional healing. The ability of an animal to bond with a member of another species—not out of fear, but out of joy—might be built right into the brain’s architecture.

More Than Imagination

One of the most poignant moments in the study comes not from a chart or a neuron, but from a quote by Dr. Hayashi herself. “We have always been curious about how humans and animals can form bonds despite having no shared language or lifestyle,” she said. “We wondered whether the connection we felt with animals was real or just our imagination.”

The answer is clear now. It’s real.

Tickled rats aren’t pretending. They aren’t tolerating the human touch because they’re confused or manipulated. They are genuinely forming emotional attachments. They are learning to love the hand that tickles them.

This finding confirms something pet owners have long suspected but could never prove—that animals can truly bond with us, and not just because we feed them. They can form attachments through affection, and these attachments are biologically grounded, not just behaviorally convenient.

Toward a Touch-Based Therapy

The implications of this research extend far beyond rats. In an age where many people struggle with loneliness, anxiety, and social disconnection, understanding the role of touch in emotional bonding could offer a path to healing.

Dr. Hayashi’s team suggests that their findings could contribute to new therapeutic strategies for people who struggle with social interactions. For individuals on the autism spectrum, or those dealing with trauma or attachment disorders, physical interaction with companion animals has long been observed to be helpful—but the mechanisms have remained unclear.

This new research suggests that oxytocin signaling, particularly in the VMHvl, may be part of why animals like therapy dogs or emotional support animals are so effective. They aren’t just comforting—they’re chemically bonding. The brain is literally building new circuits of trust and connection, one gentle touch at a time.

Bridging the Species Divide

In the end, what began as a curious observation—that rats laugh when tickled—has evolved into a groundbreaking discovery. It tells us that affection is not bound by species. That even in a world divided by fur and skin, whiskers and fingers, we can reach across with something as simple and profound as touch.

The rat, often a symbol of fear or filth in human culture, emerges here as a symbol of something else: vulnerability, playfulness, and connection. In learning to love a human hand, it reveals a secret that science is only just beginning to understand.

We do not need words to bond.

We need warmth, repetition, safety—and yes, even a little bit of laughter in the dark.

Reference: Himeka Hayashi et al, Oxytocin facilitates human touch-induced play behavior in rats, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.05.034