Long before the COVID-19 pandemic taught the world the meaning of “viral transmission,” “mask mandate,” and “quarantine,” a silent epidemic was already brewing—one not among humans, but among our closest living relatives in the animal kingdom: chimpanzees. Deep in the emerald rainforests of Uganda, a haunting story unfolded in the final hours of 2016 that would reshape the future of primate conservation. On December 31, an invisible killer swept through Ngogo in Kibale National Park, the site of the world’s longest-running chimpanzee study. The culprit? A virus that originated in humans.

The Ngogo chimpanzee community had been carefully observed for decades, revealing intricate behaviors, social structures, and individual life histories. But that New Year’s Eve marked a somber turning point. By the time the outbreak ended, 25 chimpanzees—more than 10% of the population—had died. What was once a haven of discovery became a scene of loss and urgency. Scientists had long suspected that viruses could jump from humans to wild apes, but now they had devastating proof.

This tragic event catalyzed a new chapter in conservation science—one that might finally provide the answers to an age-old question: How do we protect our evolutionary cousins from ourselves?

From Curiosity to Crisis: The Origins of the Ngogo Project

Located deep in the heart of Kibale National Park, the Ngogo field site is a biological jewel box—lush, secluded, and rich in biodiversity. Since 1994, the Ngogo Chimpanzee Project has studied its resident chimps with an unprecedented level of intimacy and dedication. Researchers at Ngogo don’t merely observe from afar; they walk among the chimps’ trails, catalog their calls, track their interactions, and collect the biological clues they leave behind.

What made Ngogo so special—its isolation, its stable population, and its low human footprint—also gave scientists a unique opportunity. Without the pressures of hunting or habitat destruction, these chimps provided a rare, unfiltered glimpse into what chimpanzee society looks like when left undisturbed. It’s no surprise the site gained international fame, recently spotlighted in Netflix’s Chimp Empire.

But this closeness, while scientifically fruitful, brought with it a silent danger. The very act of studying these primates up close introduced new risks: exposure to human pathogens.

A Deadly New Year: The 2016 Viral Outbreak

As 2016 came to a close, researchers at Ngogo were preparing to celebrate another year of data collection and discovery. Instead, they were met with signs of distress. Chimpanzees, normally robust and active, began coughing, wheezing, and displaying symptoms eerily familiar to humans suffering from respiratory infections.

What began as isolated illness quickly became a cascade of death. Within weeks, 25 chimps had succumbed to the disease. The loss was not just biological—it was deeply emotional. These were individuals known by name and personality. Their deaths left holes in family units and disrupted the delicate social balance that had been built over decades.

Subsequent analysis traced the outbreak back to a human virus, likely brought into the forest unknowingly by a researcher or staff member. Though safety protocols already existed—such as maintaining a minimum distance of 15 feet and prohibiting symptomatic researchers from entering the forest—they had not been enough.

The Science of Containment: A New Era of Protocols

The urgency was undeniable. After the outbreak ended in early 2017, the Ngogo team, led by primatologist Dr. Jacob Negrey, implemented a much stricter set of health protocols. These included mandatory face masks, hand sanitation, changing clothing before entering the forest, and a new distancing rule—20 feet minimum, with a target of 30 feet. Anyone exhibiting symptoms of illness was barred from entering the forest entirely.

By 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic erupted worldwide, Ngogo added another layer: a one-week quarantine for anyone arriving from outside the field site.

For Negrey and his team, the timing of the global pandemic paradoxically provided a proof of concept. The same public health strategies now employed worldwide—masks, quarantine, distancing—were already being practiced in this tiny outpost of the Ugandan rainforest.

“We knew the protocols should work, but we didn’t yet have the data to show that they did work,” said Negrey, who co-directs the Ngogo Chimpanzee Project and has spent more than a decade in the field.

That evidence would soon arrive, not in hospital charts or contact tracing logs, but in chimpanzee poop.

From Feces to Findings: Proving the Protocols

In the world of primatology, poop is gold. It carries DNA, hormones, and viral remnants that offer researchers a non-invasive window into the health of wild animals. Negrey’s team analyzed nearly 70 fecal samples collected from 2015 to 2019—spanning the pre-outbreak, outbreak, and post-outbreak periods.

What they found was striking.

Before the outbreak and the tightened protocols, chimpanzee samples frequently showed genetic material from viruses known to infect humans. But after the protocols were put into place, the viral load in fecal samples dropped dramatically.

So did symptoms. Before the outbreak, researchers documented chimps coughing 1.73% of the time—a seemingly small number, but significant for an animal that doesn’t routinely cough unless sick. After the new safety rules, that figure plunged to 0.356%. By 2022, after quarantine measures were introduced, it dropped even further to a barely-there 0.075%.

For the first time, science had hard data showing that protecting apes from human illness wasn’t just a hopeful aspiration—it was a measurable success.

The Broader Implications: Tourism, Conservation, and the Human-Ape Interface

While Ngogo is primarily a research site, many other chimpanzee habitats across Africa are tourist destinations. These sites are economic lifelines for local communities, generating income and awareness through eco-tourism. But they also present a serious epidemiological risk.

“Tourists may be healthy and symptom-free, but they come from all over the world, carrying all sorts of pathogens,” said Negrey. “We have really good reasons to think that chimpanzees who are visited regularly by tourists are at even greater risk than research-site chimps.”

What’s happening at Ngogo, then, is not just a story about one chimpanzee community—it’s a microcosm for global primate conservation. The findings from Negrey’s research have already begun to influence international guidelines, including those issued by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

It’s also a wake-up call. If we fail to limit human-induced disease transmission, we may not need deforestation or poaching to drive great apes to extinction. Our germs alone may do the job.

A Personal Journey: From Gorilla Dreams to Chimpanzee Realities

For Negrey, the journey to Ngogo wasn’t a straight line. As a child, he was captivated by gorillas at the zoo. He started college in Ohio as a journalism major, envisioning a life of words rather than wildlife. But a serendipitous encounter with a primatologist changed everything.

After switching his major to anthropology, he immersed himself in the biology, behavior, and evolutionary history of primates. Eventually, his focus narrowed to health—especially how diseases spread through wild chimpanzee populations and how age and immunity shape their fates.

Today, he wakes up at dawn in the Ugandan rainforest, dodges elephants on foot, and collects stool samples under the canopy. It’s demanding, sweaty, and unpredictable work, but for Negrey, it’s a calling.

“You have to really love the chimps and love the work that you’re doing,” he said with a smile. “There’s a good chance you’re going to be peed on.”

Protecting Them, Protecting Ourselves

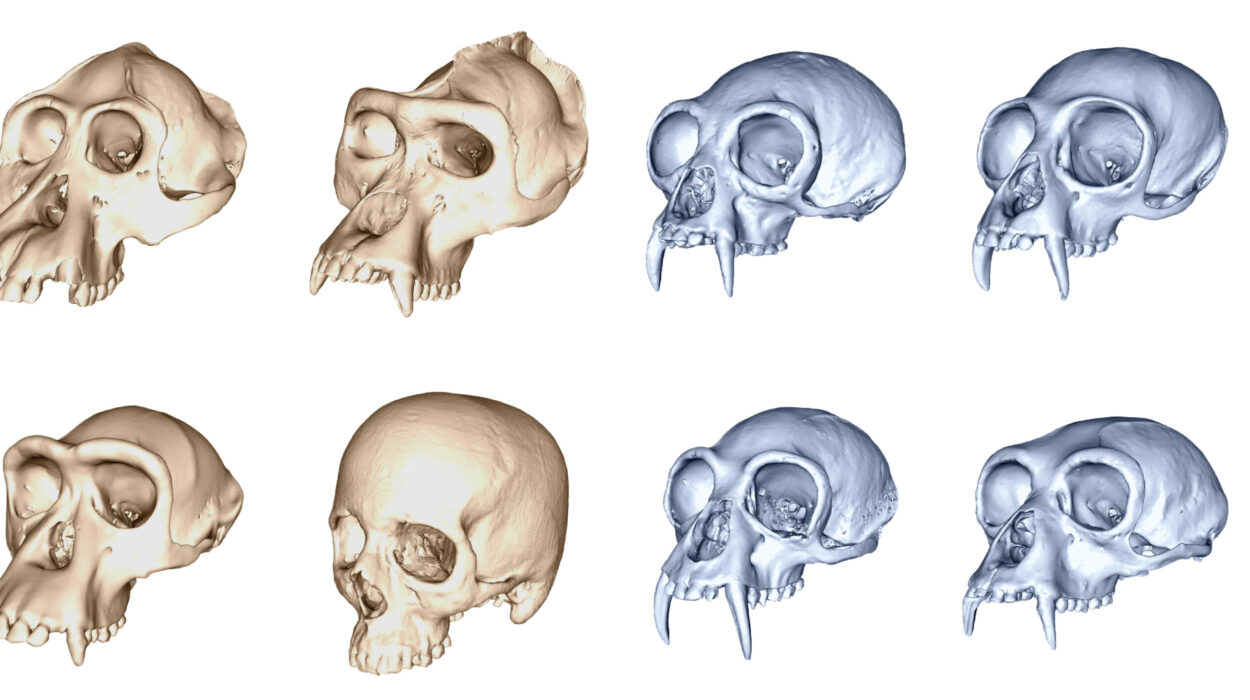

It’s no coincidence that the viruses most threatening to wild primates originate in humans. We are their evolutionary cousins—genetically, anatomically, and immunologically. Our pathogens recognize their bodies as familiar terrain.

But that closeness also holds promise. Studying how diseases spread in chimpanzees can teach us not just about them, but about ourselves. It’s a biological mirror, reflecting our own vulnerabilities and responsibilities.

“They’re so special,” said Negrey. “They’re so weird, and they’re really unlike anything else on Earth. It’s to our great benefit to protect them for future generations so we can continue to be awed by them and continue to learn from them.”

In a world where pandemics have made us hyper-aware of invisible threats, the story of Ngogo reminds us that disease knows no species boundaries. The health of wild animals, especially those as close to us as chimpanzees, is entwined with our own.

The fate of the Ngogo chimps—and of many other great ape communities—may ultimately hinge on whether humans can learn not only from science, but from empathy. Because sometimes, the best way to protect what’s wild is to look in the mirror and change what’s human.

Reference: Jacob D. Negrey et al, Decreases in chimpanzee respiratory disease signs and enteric viral quantity following implementation of anthroponotic disease prevention protocols at a long-term research site, Biological Conservation (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2025.111225