Deep inside your body, on your skin, and in the air around you, there exists a vast, invisible world of life. It doesn’t walk or talk, and it can’t be seen with the naked eye—but it is absolutely essential to your existence. This world is the microbiome—a bustling metropolis of trillions of microorganisms living symbiotically with us, influencing our health, shaping our immune systems, and even affecting how we think and feel.

For centuries, microbes were cast as villains. They were the agents of disease, the unseen enemies behind cholera, tuberculosis, and the flu. But in recent decades, a scientific revolution has taken place. We’ve come to understand that not all microbes are harmful. In fact, many are not only benign but vital to life. The microbiome represents one of the most important frontiers in modern biology, unlocking insights into who we are, how we heal, and what it means to be human.

The Microbial Universe: What Exactly Is a Microbiome?

The term microbiome refers to the entire collection of microorganisms—bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea, and even protozoa—that inhabit a particular environment. When we speak of the human microbiome, we mean all the microbes that reside on and within the human body. Each of us carries around more microbial cells than human cells—by some estimates, the ratio is roughly one to one, but microbial genes outnumber human genes by at least 100 to 1. Genetically speaking, you are more microbe than human.

These microbes inhabit every corner of your body: your mouth, lungs, skin, gut, and even your eyes. They form intricate ecosystems that are as dynamic and complex as rainforests. The gut microbiome, which has received the most scientific attention, harbors over 1,000 different species of microbes, each playing distinct roles in digestion, immunity, and metabolism.

The term microbiome is sometimes used interchangeably with microbiota, but there is a subtle distinction. Microbiota refers to the actual organisms themselves, while microbiome includes both the organisms and their collective genetic material. It’s like comparing the population of a city to the city’s culture, institutions, and architecture.

Birth of a Microbiome: The First Seeds of Life

The story of your microbiome begins even before you are born. For a long time, it was believed that the womb was sterile and that babies only acquired microbes during birth. Recent evidence has challenged that idea, suggesting that some microbial exposure may begin in utero, although this remains a topic of debate.

What is clear is that a baby’s microbial life begins in earnest during delivery. A vaginal birth exposes the infant to the mother’s vaginal and gut microbiota, seeding the baby with bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bacteroides. In contrast, babies born via Cesarean section tend to be colonized first by skin microbes and environmental bacteria—differences that can influence immune development and have been linked to increased risks of allergies and asthma later in life.

Breastfeeding continues the process of microbial colonization. Human milk is rich in complex sugars called human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) that babies cannot digest. Instead, these sugars are food for beneficial gut bacteria, especially Bifidobacteria, which help establish a healthy gut environment. These early microbial interactions play a critical role in shaping a baby’s immune system, metabolism, and even brain development.

The Gut Microbiome: A Central Control Room

Though the microbiome exists throughout the body, the gut is its most densely populated and influential region. The adult human colon contains over 100 trillion microorganisms—a number that’s hard to comprehend. If all your gut bacteria were lined up end to end, they’d stretch around the Earth two and a half times.

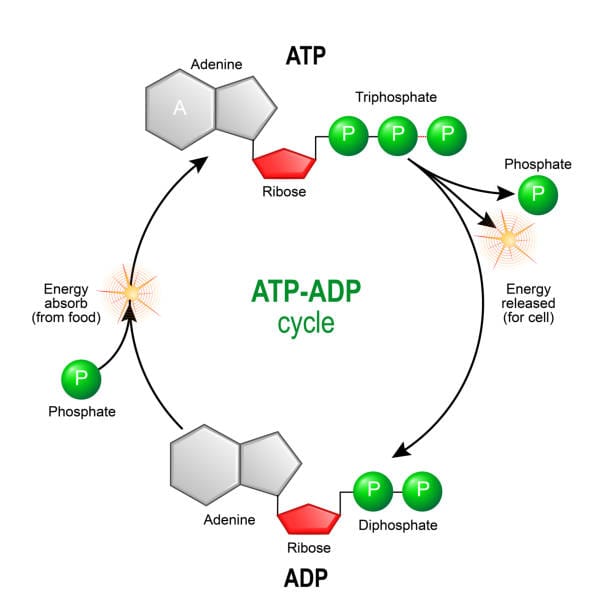

These gut microbes perform functions so essential that some scientists consider the microbiome to be a “forgotten organ.” They break down dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that nourish colon cells and reduce inflammation. They synthesize essential vitamins like B12 and K2. They help regulate metabolism, influence fat storage, and communicate with the brain through the gut-brain axis.

This gut-brain connection is one of the most exciting areas of microbiome research. It turns out that your gut microbes produce neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and GABA—chemicals involved in mood, sleep, and cognitive function. The vagus nerve, which connects the gut to the brain, serves as a two-way communication highway, allowing your microbiome to influence your mental state. It’s no wonder researchers have dubbed the gut the “second brain.”

Microbiomes Beyond the Gut

Although the gut microbiome garners most of the attention, other parts of the body have their own specialized microbiomes. The skin, for example, is home to distinct microbial communities that vary by location. The armpits, oily forehead, and dry forearms each host unique combinations of bacteria and fungi, forming a personalized protective barrier against pathogens.

The oral microbiome includes over 700 microbial species that help maintain dental and gum health, but when imbalanced, can contribute to tooth decay and periodontal disease. The respiratory tract, once thought to be sterile, has its own microbial residents that influence susceptibility to infections like pneumonia.

The vaginal microbiome is another important ecosystem, dominated by Lactobacillus species that help maintain a low pH environment hostile to harmful pathogens. Disruptions to this microbiome can lead to bacterial vaginosis and increased risk of sexually transmitted infections.

Each of these microbiomes is finely tuned to its environment, and all are deeply interconnected. Changes in one site can influence others, demonstrating the integrated nature of the body’s microbial networks.

Symbiosis and Survival: Microbes as Partners

Microbes and humans have co-evolved for millions of years. This long-term relationship is not one of parasitism or dominance, but of mutual benefit—symbiosis. We provide microbes with food and shelter; in return, they help us digest food, train our immune systems, and protect us from harmful invaders.

This partnership is not static—it’s a dynamic interplay influenced by diet, lifestyle, genetics, environment, and even emotions. Every time you eat, take an antibiotic, travel to a new place, or feel stressed, your microbiome shifts in subtle ways. Some of these changes are temporary; others may have lasting effects.

One of the most remarkable roles of the microbiome is immune education. During early life, microbes help the developing immune system learn the difference between friend and foe. A well-trained immune system tolerates harmless substances like pollen or food proteins while targeting real threats like viruses and cancer cells. When this process goes awry—due to a disrupted microbiome or genetic predisposition—autoimmune diseases and allergies can arise.

The Microbiome and Modern Disease

A growing body of research links microbiome imbalances—known as dysbiosis—to a wide range of diseases. These include obvious gastrointestinal conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Crohn’s disease, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but also systemic illnesses such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even certain cancers.

In obesity, for example, studies have shown that people with a less diverse gut microbiome tend to gain weight more easily. Some microbes extract more energy from food, while others influence hormones that regulate appetite. In animal models, transferring gut microbes from obese mice to lean ones can cause the lean mice to gain weight—even when eating the same amount of food.

In mental health, alterations in the gut microbiome have been associated with depression, anxiety, and autism spectrum disorders. Though these correlations are still being untangled, the evidence suggests that microbial health could play a role in psychological well-being.

Even conditions like Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s are being investigated through a microbial lens. Inflammation, gut permeability, and microbial toxins may all contribute to the complex web of causes behind these neurodegenerative disorders.

Healing Through the Microbiome: Therapies and Treatments

As our understanding of the microbiome deepens, so too does the potential for new therapies. Already, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been used with remarkable success to treat recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections, a life-threatening form of diarrhea that often follows antibiotic use. By transplanting stool from a healthy donor into a patient’s gut, doctors can restore a healthy microbial balance.

Probiotics—live microorganisms believed to confer health benefits—have become popular, though their effectiveness varies by strain and condition. More precise approaches, including targeted bacteriotherapy, are under development. These therapies aim to use specific microbes or microbial products to treat disease, avoiding the pitfalls of broad-spectrum antibiotics or untargeted probiotics.

Prebiotics, compounds that feed beneficial microbes, also hold promise. Found in foods like onions, garlic, bananas, and chicory root, prebiotics can encourage the growth of health-promoting bacteria. Synbiotics combine both pre- and probiotics for synergistic effects.

Perhaps the most revolutionary idea is microbiome engineering: using gene editing, synthetic biology, or microbiome transplants to reshape microbial communities deliberately. While still in its infancy, this approach could transform medicine in the coming decades.

The Microbiome and Personalized Medicine

Every person’s microbiome is unique, shaped by their genes, environment, diet, and history. This uniqueness makes the microbiome a powerful tool for personalized medicine. Already, researchers are developing microbiome-based diagnostics that can predict an individual’s risk for certain diseases, guide treatment choices, and monitor responses to therapy.

For example, cancer immunotherapy—treatments that harness the body’s immune system to attack tumors—works better in patients with certain gut microbes. By analyzing and modifying the microbiome, doctors may one day be able to improve the effectiveness of cancer treatments and reduce side effects.

The dream of tailoring health care to an individual’s microbial profile is no longer science fiction. With advances in DNA sequencing, artificial intelligence, and microbiome analytics, personalized microbial medicine is on the horizon.

Challenges, Controversies, and the Road Ahead

Despite the promise of microbiome science, it’s important to acknowledge its challenges. The field is still young, and many findings are preliminary or based on animal studies. Human microbiomes are incredibly diverse, making it difficult to draw universal conclusions. The causal links between microbiome changes and disease are often hard to establish—is the microbiome causing the disease, or is the disease altering the microbiome?

There are also ethical and regulatory questions surrounding microbiome interventions. Who owns your microbiome data? Should we regulate microbial transplants the way we do organ donations? Can we patent a gut bacterium?

Moreover, the commercialization of microbiome science has outpaced the evidence. While some probiotic products are supported by research, many are not. Consumers are bombarded with microbiome-related claims, but the science doesn’t always support the hype.

Still, the potential is immense. As techniques improve and datasets grow, researchers will better understand the precise roles of different microbes, their interactions, and their effects on human health. The coming years will likely see a shift from descriptive studies to mechanistic insights and targeted therapies.

A New Lens on Life

The discovery of the microbiome has changed how we think about ourselves—not as isolated beings, but as ecosystems. We are not alone in our bodies; we are superorganisms, shaped and sustained by a vast network of microbial life. This realization blurs the line between self and other, biology and ecology, health and environment.

It also reconnects us to nature. The rise in autoimmune diseases, allergies, and chronic inflammation has been linked to a “disconnection” from our microbial roots—a phenomenon known as the hygiene hypothesis. Our obsession with cleanliness, antibiotics, and processed foods may be stripping away the microbial diversity that once protected us.

The solution is not to fear microbes, but to understand them, nurture them, and live in harmony with them. Whether by eating more fermented foods, spending time in nature, or reducing unnecessary antibiotics, we can begin to restore our microbial balance.

Conclusion: You Are Your Microbiome

The microbiome is not just a scientific curiosity—it’s a fundamental part of what it means to be alive. It influences your digestion, your mood, your immunity, your appearance, and perhaps even your identity. It connects you to your ancestors, to the earth, and to the future of medicine.

To study the microbiome is to embark on a journey into an unseen world—one that is intricate, dynamic, and profoundly beautiful. It is a reminder that the smallest forms of life can have the biggest impact—and that the key to our health may lie not in conquering nature, but in understanding and embracing it.

You are not alone. You never have been. And that’s the most extraordinary part of all.