When paleontologists first laid eyes on Shishania aculeata, the fossil was a riddle wrapped in spikes. Unearthed from the 500-million-year-old Cambrian strata of Yunnan Province in southern China—a region famous for its astonishingly well-preserved ancient creatures—Shishania seemed to be a long-lost relative of today’s mollusks. Its spiny silhouette, hinting at armor-like protection, and what appeared to be a muscular foot led scientists to believe they were looking at a primitive ancestor of clams, snails, or slugs.

But in a twist as dramatic as anything in science fiction, a new study led by researchers from Durham University and Yunnan University has revealed that Shishania is not a mollusk at all. Instead, it belongs to a different, stranger branch of the animal tree—an ancient, sponge-like lineage known as chancelloriids. This reclassification doesn’t just rewrite a chapter of paleontological textbooks; it forces scientists to reconsider some of their core assumptions about how the earliest animals evolved.

Cracking Open the Cambrian Code

The Cambrian period, often dubbed the “Biological Big Bang,” was a time of explosive evolutionary experimentation. Around 540 million years ago, nature rolled the dice, producing an incredible diversity of animal forms in a geologically brief burst. Among these were the first representatives of almost all modern animal groups. In this crucible of biological innovation, some lineages took off and diversified; others, like the chancelloriids, left behind only a cryptic fossil trail.

Chancelloriids were peculiar animals—bag-like, sessile creatures encrusted with elaborate, star-shaped spicules. They resembled armored sea sponges, yet their exact relationships to other animal groups have remained murky. Their fossils are found only in Cambrian-aged rocks and vanish mysteriously around 490 million years ago. What they truly were, or how they fit into the tree of life, has long been debated.

Enter Shishania aculeata, a spiny fossil that seemed to hold answers. Described initially in 2023, Shishania was thought to bridge the gap between mollusks and their deep-time ancestors. Its body shape, its supposed muscular foot, and its radiating spines seemed to make it a key player in the evolutionary origin story of mollusks. But appearances, as it turns out, can be deceiving—especially when shaped by 500 million years of geological processes.

Fossil Origami and Taphonomic Tricks

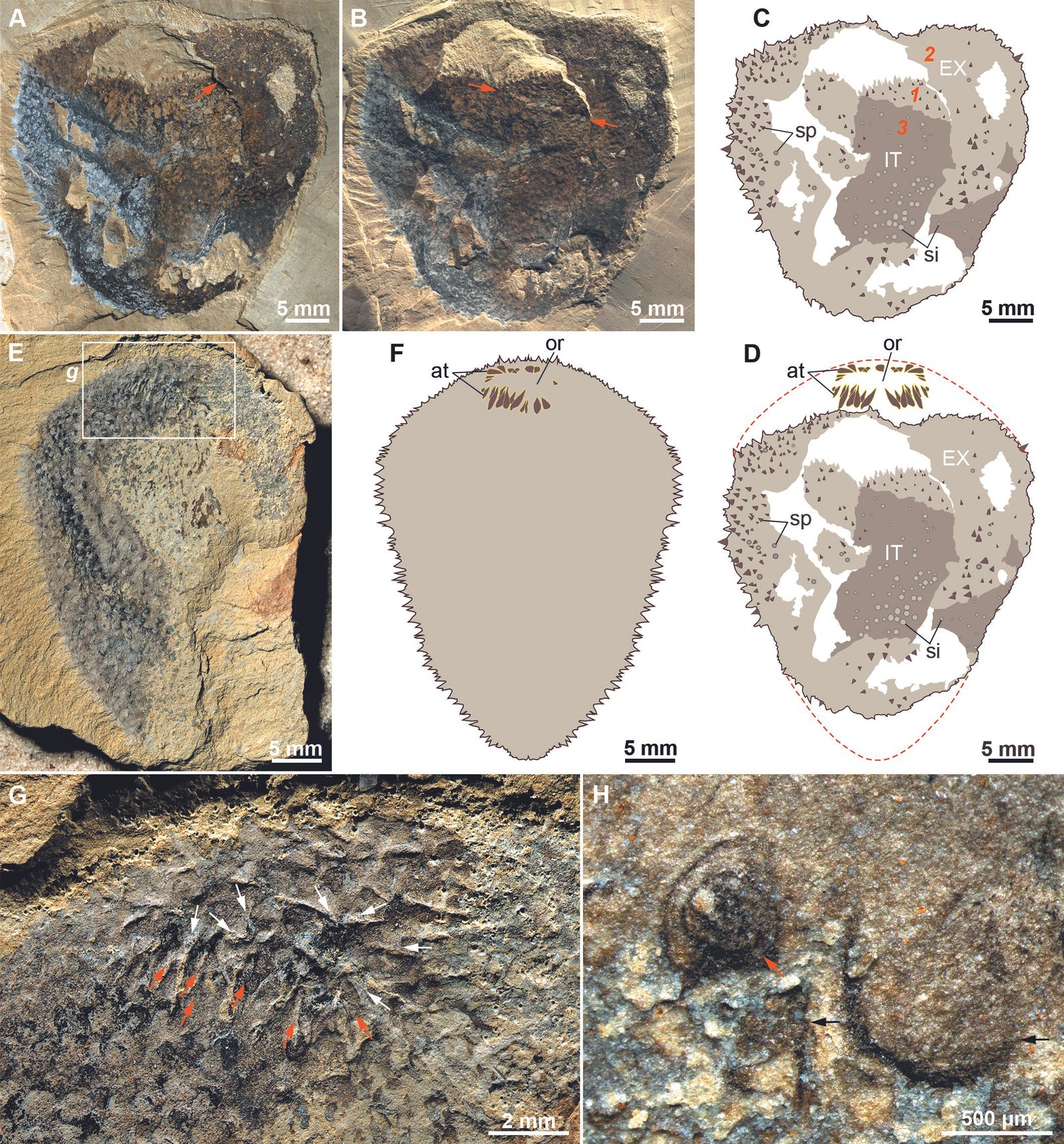

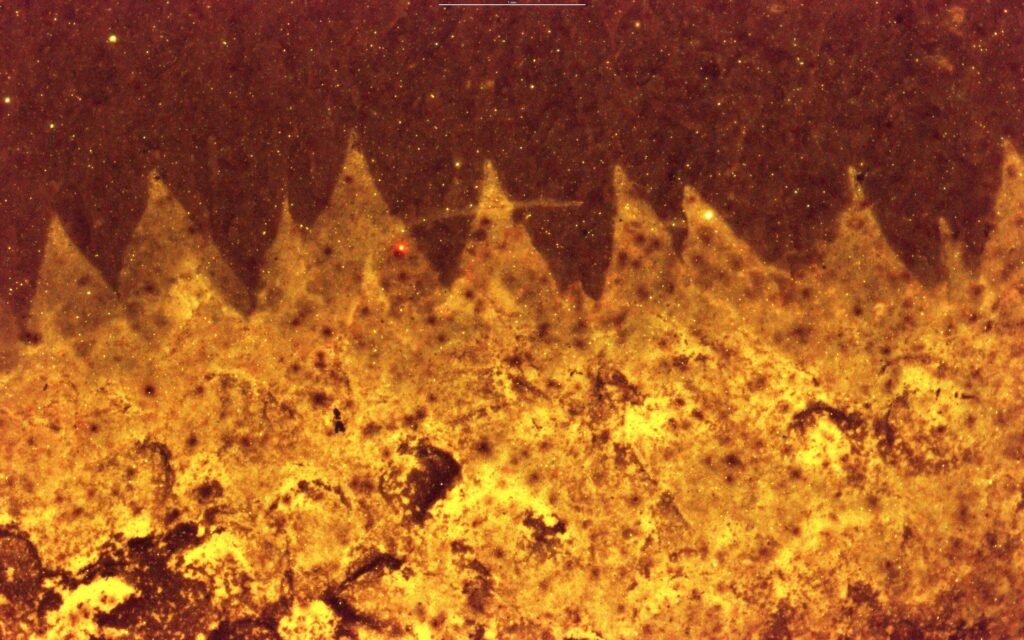

The team of scientists, led by Dr. Martin Smith of Durham University and Chinese paleontologists from Yunnan University, took a second, much closer look at newly uncovered Shishania specimens. Using high-resolution imaging and 3D reconstruction techniques, they were able to peer beneath the fossil’s surface—literally and metaphorically.

What they discovered was a case of fossil fraud—but not the intentional kind. Instead, they were dealing with what scientists call a “taphonomic illusion.” Taphonomy is the study of what happens to organisms after they die, including how they decay, are buried, and eventually fossilize. In the case of Shishania, the process had folded and compressed the body in such a way that anatomical features appeared to be present when they actually weren’t.

For instance, the so-called “foot,” which had been one of the main pieces of evidence linking Shishania to mollusks, turned out to be a product of fossil distortion. Rather than an actual muscular organ used for movement, it was a flattened region caused by the fossil being compressed under layers of sediment. Similarly, the pattern of the spines—initially described as being in a “paintbrush-like” arrangement typical of certain mollusks—was revealed to be completely random. These patterns were not biological at all, but the result of post-mortem deformation.

The Chancelloriid Revelation

What truly unraveled the mystery was the discovery that other fossils from the same rock layer, now definitively identified as chancelloriids, had undergone similar distortion—and ended up looking uncannily like Shishania. This realization forced the researchers to reassess every feature they had previously attributed to molluscan biology. When reinterpreted in light of these better-preserved chancelloriid specimens, Shishania’s anatomy no longer made sense as a mollusk but perfectly aligned with what’s known about chancelloriids.

Dr. Martin Smith described the experience as a humbling intellectual pivot. “These ancient fossils turned out to be masters of disguise,” he explained. “At first glance, Shishania seemed to tick all the boxes for a mollusk ancestor. But as we peeled back each layer of misinterpretation, the true identity of this creature began to emerge.”

In short, Shishania aculeata had pulled off one of the greatest masquerades in paleontological history. Not a mollusk at all, but a spiny, sessile chancelloriid—closer in form to a sponge than a snail.

The Evolutionary Significance of Spines

What makes this reclassification even more exciting is what it reveals about the evolution of chancelloriids themselves. Unlike the ornate, star-shaped spicules seen in most members of this group, Shishania’s spines are remarkably simple. This suggests that the more elaborate skeletal elements seen in later chancelloriids didn’t evolve by modifying existing structures, as is often the case in evolution, but arose de novo—from scratch.

This insight has sweeping implications for our understanding of how complex body plans emerged during the Cambrian explosion. It challenges the idea that major innovations always evolve incrementally. In the case of chancelloriids, their defensive armor may have sprung into existence through a relatively rapid evolutionary process, independent of earlier skeletal structures.

The presence of simple spines in Shishania offers a potential evolutionary snapshot—capturing the early stages of a trend that would become more exaggerated in its descendants. It’s as if paleontologists have stumbled upon the prototype of a biological arms race in its infancy.

A New Cautionary Tale in Paleontology

Beyond its immediate scientific importance, the Shishania saga serves as a cautionary tale for paleontologists. Fossils are notoriously difficult to interpret. They are, after all, the weathered remnants of once-living organisms that have been squashed, stretched, mineralized, and eroded over hundreds of millions of years. A single misleading detail can send researchers down the wrong interpretive path—sometimes for decades.

The Shishania misidentification reminds scientists to tread carefully when analyzing ambiguous features and to consider the possibility that what they’re seeing is not what it seems. It also emphasizes the importance of context—both geological and biological. The fact that Shishania was found in association with clearly identified chancelloriids provided the critical clue that ultimately led to its correct classification.

Rediscovering the Cambrian Landscape

The discovery also highlights the extraordinary value of the fossil beds in Yunnan Province, particularly the famed Chengjiang biota. These deposits offer a rare glimpse into Cambrian ecosystems, preserving soft tissues and intricate body structures that are usually lost to time. It is thanks to these exceptional conditions—and the persistent efforts of Chinese paleontologists—that such evolutionary mysteries can be unraveled.

Moreover, the study underscores the importance of international collaboration in modern science. It took the combined expertise of researchers from Durham University and Yunnan University—bringing together Western and Eastern approaches to paleontology—to reanalyze Shishania and unlock its secrets. As the study’s findings ripple through the scientific community, they demonstrate how partnerships across borders can enrich our understanding of life’s earliest history.

A Window into Evolution’s Creative Chaos

In the end, Shishania aculeata reminds us that the story of life on Earth is not a linear march toward complexity, but a chaotic, experimental explosion of forms. Some of these forms, like mollusks, went on to dominate the seas and land. Others, like the chancelloriids, flickered briefly in Earth’s evolutionary theater before vanishing, leaving behind only cryptic traces.

And yet, even those ephemeral players have much to teach us. In correcting a misinterpretation, scientists have gained new insight into how innovation works in evolution—not always through slow modification, but sometimes through sudden, radical novelty. It’s a reminder that evolution is not just a blind watchmaker, but also a tinkerer, a sculptor, and sometimes a gambler.

The fossil of Shishania, once a would-be mollusk and now a proud chancelloriid, has become a symbol of the surprises still hidden in ancient stone. As Dr. Smith put it, “These creatures were trying out ways of being animal that have no modern parallels. Their legacy is not in descendants, but in showing us how strange, how creative, and how unpredictable evolution can be.”

Reference: Jie Yang et al, Shishania is a chancelloriid and not a Cambrian mollusk, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adv4635. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adv4635