Long before humans carved hearts into trees or peacocks fanned their feathers under the sun, there were dinosaurs—colossal, thunderous, and surprisingly romantic. Deep in prehistoric Colorado, in what is now a fossil-rich region known as Dinosaur Ridge, ancient creatures once gathered in droves on mudflats to perform dances of love. These weren’t just isolated rituals—they were spectacular mating displays, likely repeated for generations.

Now, using modern technology to peer into Earth’s ancient past, a team of U.S.-based paleontologists believes they’ve uncovered the largest known dinosaur mating dance arena ever discovered. Their findings, published in the journal Cretaceous Research, reveal a world where courtship wasn’t whispered—it shook the ground.

Where Dinosaurs Danced for Love

Dinosaur Ridge, on the edge of the Rocky Mountains, has been a paleontological treasure chest since the 1800s, famous for its bones and fossilized tracks. But this new research focused on something different—the behavior of dinosaurs. Instead of just asking how they lived or died, the scientists wanted to know how they loved.

At the base of the ridge lies a once-tidal flat, a muddy stretch that would have been flooded periodically millions of years ago. These floodplains, now stone, were where dinosaurs congregated. Not to eat. Not to fight. But to dance.

The phenomenon the researchers were investigating is called “lekking,” a mating behavior still practiced by some modern birds today, such as sage grouse. In a lek, males gather in a shared display ground and perform competitive dances, each trying to outshine the others to win over a watching female. These rituals often leave behind scrapes, footprints, and distinctive surface marks—echoes of a performance long gone.

A Bird’s-Eye View of the Deep Past

To uncover this prehistoric theater of romance, scientists had to rise above it. Literally.

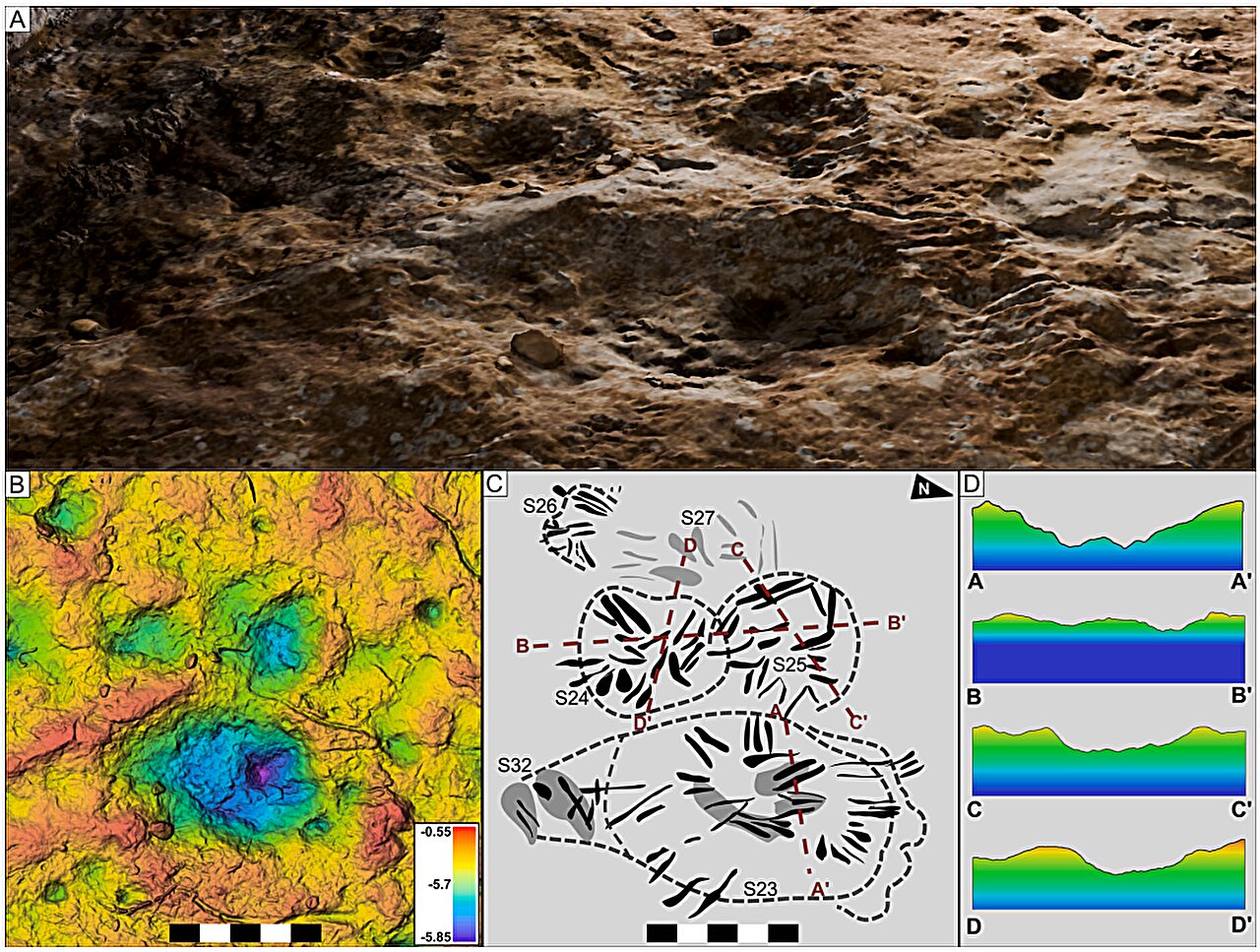

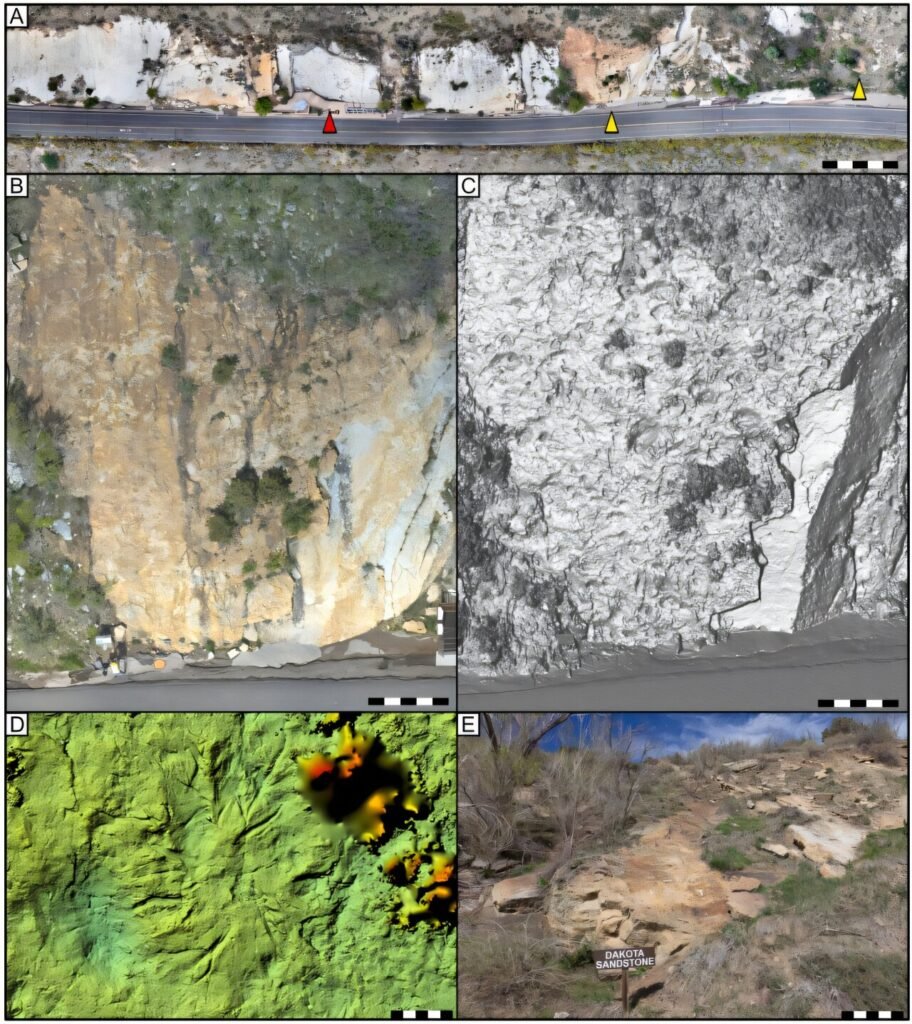

Because human foot traffic is banned in the area to protect fragile fossil evidence, researchers turned to aerial technology. Using drone imagery collected by the U.S. Geological Survey in 2019 and again in 2024, they obtained a new view of the terrain. From the air, the subtle patterns in the rock—scratches, gouges, and swirls—came alive.

What they saw astonished them.

The ground wasn’t marked by just a few scrape marks. Instead, it was covered with them, stretching across the landscape like a dance floor the size of several football fields. Some areas showed large bowl-shaped impressions. Others revealed long, thin claw marks—possibly from a dinosaur dragging its talon mid-performance. There were dozens of such marks in distinct patches, like dance circles separated across space, but all forming part of one massive “lek.”

“We realized we weren’t looking at isolated performances,” said one of the researchers. “This was a concert hall.”

Scrapes, Claws, and Stories Set in Stone

What made the discovery especially thrilling was the diversity of the markings. Some were deep and symmetrical, perhaps the result of ceremonial stomping or nest-building. Others were shallow, streaked, or oddly shaped—likely produced by varied behaviors: tail swishes, foot drags, or competitive dances.

Digging data from earlier decades confirmed that some of these sites had been used multiple times, with markings preserved in different rock layers, or strata. This means that the same lekking spots were reused, possibly by entirely different species over vast stretches of time.

In essence, Dinosaur Ridge may not have hosted just one species’ romantic rituals. It could have been the prehistoric equivalent of a dating hot spot shared across millennia—a kind of love landmark in the animal kingdom’s evolutionary history.

A Tale Repeated in Other Ancient Arenas

To better understand the Colorado site, the researchers compared it with similar fossilized lekking areas in Alberta, Canada, and other parts of Colorado. The resemblance was striking. The same kinds of markings appeared in each location, suggesting a recurring pattern of behavior across ancient ecosystems.

These weren’t random scratches in the mud. They were intentional movements—performed over and over, by creatures with the intelligence and instinct to court mates through showmanship.

The idea that dinosaurs may have danced in large social gatherings to win love isn’t entirely new. Some paleontologists have speculated on dinosaur mating rituals for years, especially based on similarities with modern birds, who are their closest living relatives. But this site provides what may be the most compelling physical evidence to date.

“We’ve known birds use leks for ages,” the lead researchers noted. “To now have such a clear fossil record suggesting that large dinosaurs might have done the same—it’s a thrilling overlap of ancient and modern behavior.”

Science Meets the Soul of Nature

Beyond the fossil evidence and drone data, the emotional weight of this discovery is hard to miss. This isn’t just a story about bones and rocks—it’s a story about behavior, about creatures doing what every species on Earth has done at some point: trying to impress, to connect, to reproduce.

It reminds us that courtship is as old as life itself, and that performance, flair, and ritual have long been part of the evolutionary game. From birds fanning feathers to humans writing poetry, love has always required effort. Even when your feet are the size of dinner plates.

These dinosaurs, many the size of buses or trucks, didn’t just stomp through mud—they expressed desire through movement. Their scrapes and marks are more than paleontological data; they’re emotional echoes.

A Stage We Never Knew Was There

The ancient tidal flats of Colorado’s Dinosaur Ridge have become a stage for one of the most powerful stories science can tell—not just of how life survives, but how it strives to connect. Every bowl-shaped impression, every claw-drag line, is a line of choreography written in stone.

In the end, this discovery doesn’t just reveal new facts about dinosaurs. It lets us feel a little closer to them. Because as alien as they may seem, they too once danced for love under open skies, on wet ground, in a world still finding its rhythm.

And now, 30 million years later, we’re finally learning to watch.

Reference: Rogers C.C. Buntin et al, A new theropod dinosaur lek in the Cretaceous Dakota Sandstone (Dinosaur Ridge, Colorado, USA), Cretaceous Research (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cretres.2025.106176