Half a billion years ago, in the ancient, shallow seas that once covered what is now the Anti-Atlas Mountains of Morocco, a peculiar animal lay buried in the sediment. It had no five arms, no radial symmetry, no star-shaped elegance. Instead, its body was bilaterally symmetrical—more like a shrimp or a worm than the starfish we know today.

Now, that fossilized creature, Atlascystis acantha, has reemerged from stone and silence, offering scientists a remarkable glimpse into one of the strangest evolutionary transitions in the animal kingdom: how starfish, sea urchins, and their relatives—collectively known as echinoderms—evolved from creatures with bilateral symmetry, like humans, into their famously unusual fivefold shapes.

Discovered by a team led by researchers from the Natural History Museum in London, the find is being hailed as a missing puzzle piece in the evolution of echinoderms. For the first time, scientists have direct fossil evidence of a transitional form between bilateral ancestors and the bizarre pentaradial forms that populate today’s oceans.

“This fossil evidence allows us to piece together how the body plans of starfish and their relatives evolved step-by-step from ancestors that were much more similar in shape to other animals,” said Dr. Imran Rahman, principal researcher at the Natural History Museum and co-lead author of the study.

An Ancient Body With Modern Secrets

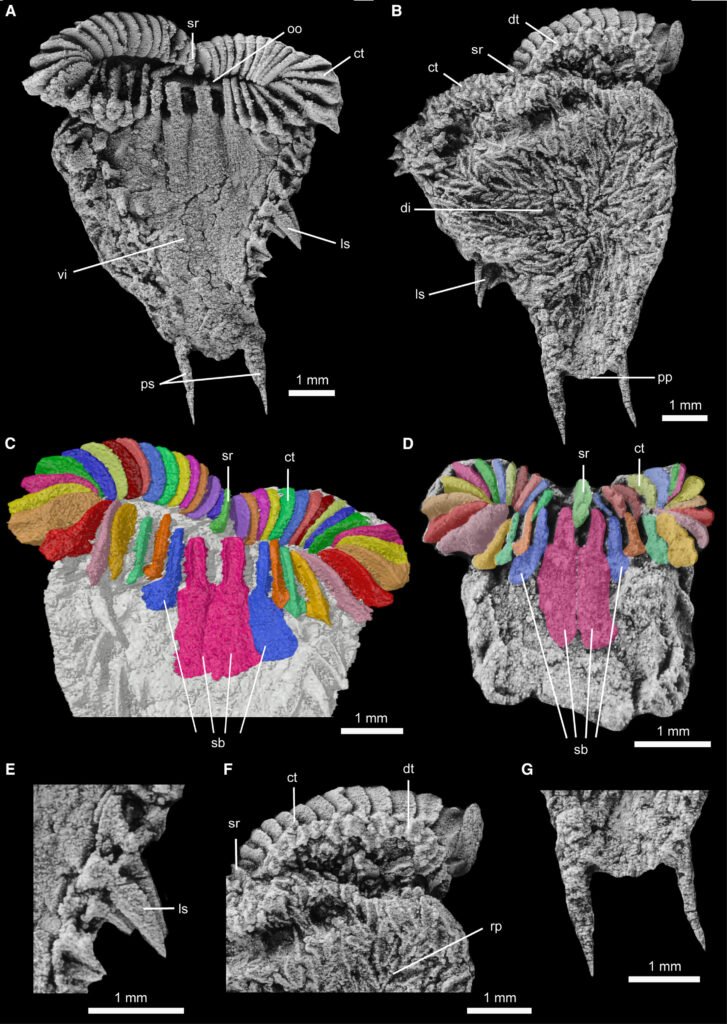

At first glance, Atlascystis acantha is a strange, alien-looking animal: a flattened, spine-covered form with a clear left and right side. But what makes it extraordinary is what it shares with modern echinoderms.

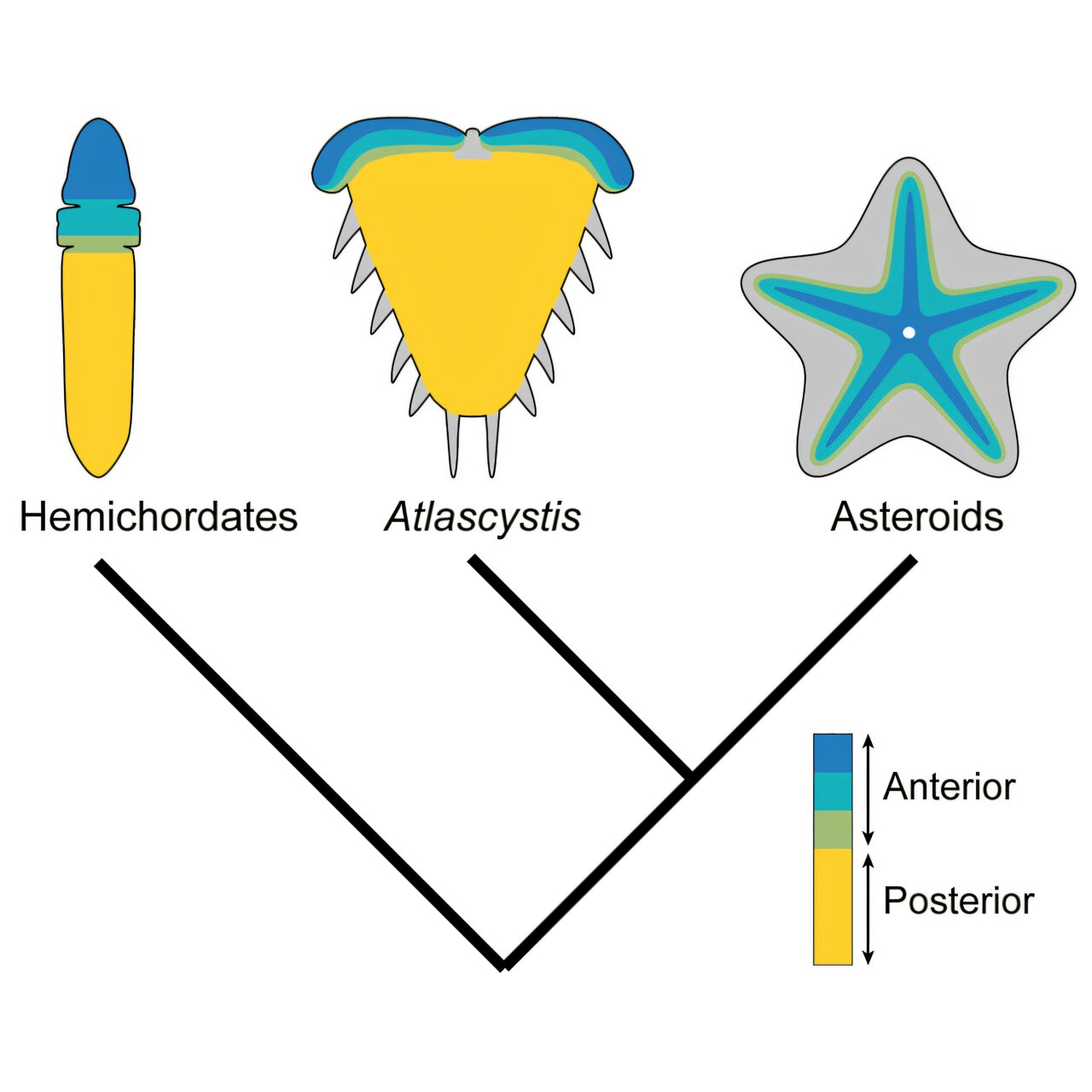

Though it lacks the starfish’s iconic five arms, Atlascystis has a pair of specialized skeletal structures known as ambulacra—grooves along the body lined with plates that in modern echinoderms are used for feeding and locomotion. This discovery shows that the genetic and structural blueprint for echinoderm body plans was already being laid hundreds of millions of years ago, even before the symmetry we associate with starfish had evolved.

The fossil’s bilateral body challenges previous assumptions that early echinoderms with two-sided symmetry were evolutionary outliers—branches that broke off from more “modern” fivefold forms. Instead, the new study suggests the opposite: that bilateral forms like Atlascystis sit at the very root of the echinoderm family tree, and that the iconic five-rayed form evolved later, as an innovation built upon these early patterns.

Unraveling an Evolutionary Mystery

The research, published in Current Biology, didn’t rely on fossil analysis alone. The team used 3D imaging and high-resolution scans to digitally reconstruct the fossil in exquisite detail. They then performed growth analyses and applied advanced phylogenetic techniques—essentially building an evolutionary tree—to determine where Atlascystis fits among its living and extinct relatives.

They found that this creature, with its bilateral body and paired ambulacra, likely represents one of the earliest stages in echinoderm evolution. The fivefold symmetry that would later define the group probably arose through the duplication of a single ambulacrum—a radical anatomical shift made possible, the authors suggest, by the disappearance of a defined head-to-tail axis (the anteroposterior axis).

“We were able to determine how this animal grew when it was alive, which was the key to understanding its place in the tree of life,” said Dr. Jeff Thompson, lecturer at the University of Southampton and a co-author on the study.

More Than Just a Fossil

While modern genetics has unlocked countless secrets of evolution, it cannot alone explain how certain body plans emerged—especially those as strange as the pentaradial symmetry of echinoderms. This is where fossils like Atlascystis become crucial.

“The fossil record remains our only direct insight into the evolutionary history of groups through time,” said Dr. Frances Dunn, senior researcher at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. “This discovery shines a light on the first steps of the evolution of one of the most recognizable body plans we find in animals today: the starfish.”

Fossils are not just bones in stone; they are echoes of evolutionary experiments. They show us how nature once tinkered with form and function, shaping the creatures that would later thrive—or vanish. And Atlascystis acantha is a testament to that process: a halfway shape between the familiar and the alien, preserved for half a billion years under Moroccan rock.

Evolution in Real Time

Echinoderms are one of nature’s most radical redesigns. While most animals—ourselves included—are built around bilateral symmetry (a clear left and right side), echinoderms took a different path, rearranging their bodies into a fivefold symmetry. It’s a body plan without parallel among animals.

That transformation has puzzled evolutionary biologists for generations. How does an animal go from a bilateral layout to one with five arms radiating out from a center point? What genetic changes made it possible? What selective pressures might have favored such a structure?

With Atlascystis acantha, scientists now have a living clue frozen in stone—a snapshot of evolution in progress. The fossil shows that early echinoderms were still experimenting with body symmetry, trying out structures that straddled the line between what came before and what would come after.

A Window Into Deep Time

The discovery of Atlascystis was made in the Anti-Atlas Mountains, a fossil-rich region that has become a global hotspot for Cambrian and Ordovician paleontology. These rocks, once buried beneath ancient oceans, now sit high above sea level, holding the secrets of a time when life was just beginning to diversify into complex forms.

And while the fossil may be half a billion years old, the questions it helps answer are among the most modern in science: How do radically new forms evolve? How flexible is the animal blueprint? What can ancient life teach us about the limits—and the possibilities—of biology?

As the team continues to study the fossil and its relatives, one thing is clear: Atlascystis acantha has rewritten a key chapter in the story of life on Earth. It reminds us that even the most alien-looking animals have ancestors that were not so different from ourselves—and that the long road from symmetry to stars is paved in stone.

Reference: Stephanie C. Woodgate et al, A new Cambrian stem-group echinoderm reveals the evolution of the anteroposterior axis, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.05.065