High above the pews and pulpit, in the forgotten shadows of ancient church attics, a strange and beautiful ritual unfolds each summer night. The darkness is thick, broken only by the flicker of moonlight through broken beams and the faint rustle of wings. Here, among the wooden rafters of rural churches, male greater mouse-eared bats (Myotis myotis) gather—not in silence, but in serenade.

With trills that echo like whispers of longing through the gloom, they sing. Not just to break the stillness, but to compete. To court. To captivate. And now, scientists have decoded their performance.

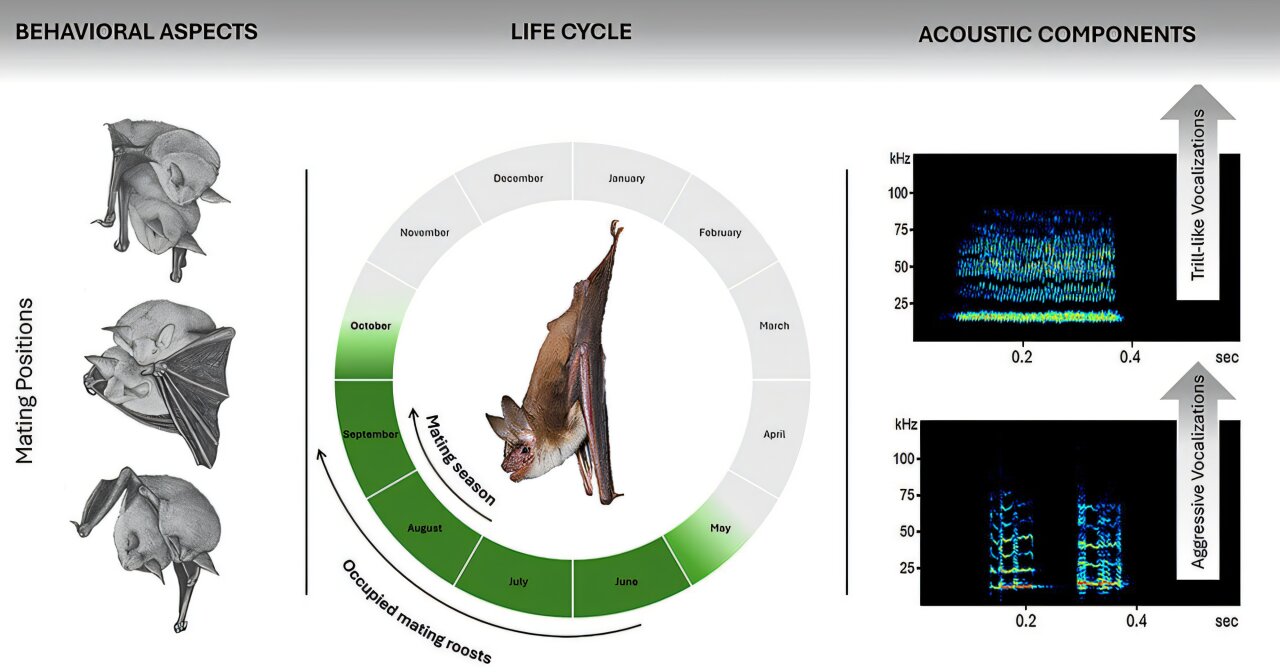

In a groundbreaking new study published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, researchers from the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin have revealed that these large European bats, often cloaked in myth and misunderstanding, exhibit a surprisingly intricate mating system known as a lek—a strategy more commonly seen in birds like peacocks or sage grouse than in nocturnal mammals.

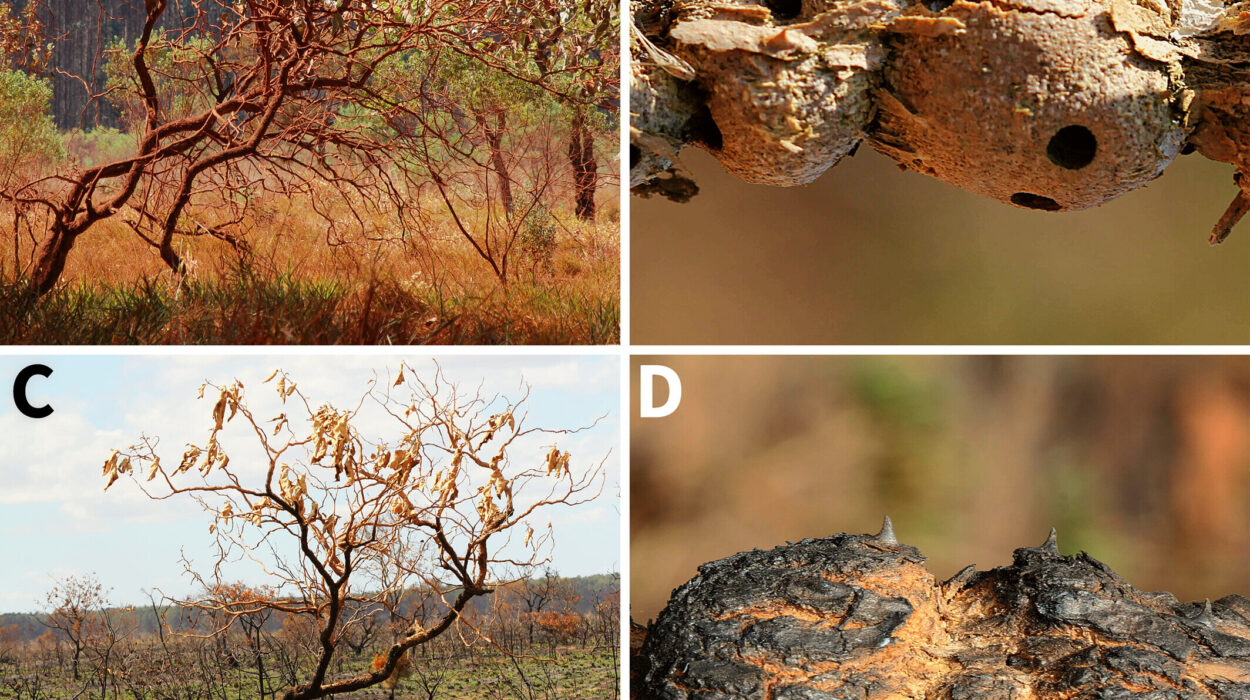

For PhD researcher Lisa Printz, who spent countless hours watching and listening in six church attics across Europe, the scene was equal parts haunting and romantic.

“For the first time, we were able to document in detail that the greater mouse-eared bat exhibits a lek mating system—a mating system previously confirmed in only a few bat species,” Printz said.

Songs of Rivalry and Romance

The lek system is a marvel of competitive courtship. Unlike many animals, these males offer no food, no nesting help, no paternal investment. They bring only their voices, their endurance, and their patience.

Each male stakes out a small, familiar roosting spot high in the attic—a kind of stage in the sky—and defends it with vigor. From there, he emits complex trill vocalizations designed both to fend off rival males and to seduce listening females. It’s a curious kind of competition: no direct fights, no grand displays, just sound, stillness, and subtlety.

Females, meanwhile, travel great distances during the mating season to visit these hidden concert halls. But they don’t land just anywhere. Intriguingly, the study found that many females make their choice mid-flight—gliding straight toward a preferred male before ever touching down.

What guides their decision? The trill? The scent? Some secret known only to bats? The answers are still elusive, but the implications are profound.

A Love That Lingers

Perhaps the most surprising revelation from Printz’s study lies not in the competition itself, but in what happens next.

When a female lands beside her chosen male, there’s no frenzy. No chaos. Instead, the pair often rest quietly together, side by side in the rafters, before mating begins. After copulation, the male wraps his wings around the female in a gesture of intimacy and protection. Sometimes, they remain in contact for hours before mating again.

One documented mating session lasted more than 34 hours.

“This prolonged mating event and subsequent resting period might represent a form of mate guarding,” explained Dr. Mirjam Knörnschild, a senior researcher at the Museum für Naturkunde. “It may help ensure successful reproduction.”

In the dim silence of those lofty attics, what appears to be a simple encounter reveals layers of subtle strategy. In the language of bats, love takes time—and sometimes, it takes a whole day and night.

A New Frontier for Conservation

For decades, conservation efforts have focused primarily on female bat roosts—maternity colonies where pups are born and raised, or hibernation sites critical for winter survival. Male bats, long believed to be wanderers with few attachments, received little attention.

This study turns that assumption on its head.

“Males also use specific roosts seasonally and show long-term fidelity to their traditional roosting sites,” said Printz. “Renovation or structural changes to buildings such as churches or monasteries could seriously disrupt the mating season.”

These male roosts aren’t just sleeping spots—they are carefully defended display arenas. A single alteration to a beam, a shift in temperature or airflow, a closed attic door, could disrupt an entire mating season. And unlike maternity colonies, these male groups are small and scattered, making them easy to overlook—and harder to protect.

The findings call for a sweeping re-evaluation of conservation practices. The authors argue that male lek sites deserve the same protection as traditional roosts. Preservation of these display spots is essential—not just for the survival of individual bats, but for the long-term health of the population.

The Hidden Opera Above Our Heads

The greater mouse-eared bat is the largest native bat species in Europe. Often misunderstood, sometimes feared, these animals are essential to our ecosystems—devouring insects, pollinating plants, and now, it seems, composing love songs in the night.

Their voices may be beyond our hearing, but their story speaks volumes.

Hidden in the dusty rafters of old churches, a secret world thrives—a world of song, devotion, and ancient rhythms played out against beams centuries old. The males return to the same spots year after year, guided by memory and instinct. The females come, choosing carefully. And together, beneath the spires and crosses, the next generation of bats begins with a whisper.

If we are to preserve these remarkable creatures, we must begin by listening. Not just with our ears, but with understanding—and with urgency.

Because sometimes, the most extraordinary stories are playing out just above our heads, in the quietest corners of the world.

Reference: Lisa Printz et al, Mating system and copulatory behavior of the greater mouse‐eared bat (Myotis myotis), Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1111/nyas.15390