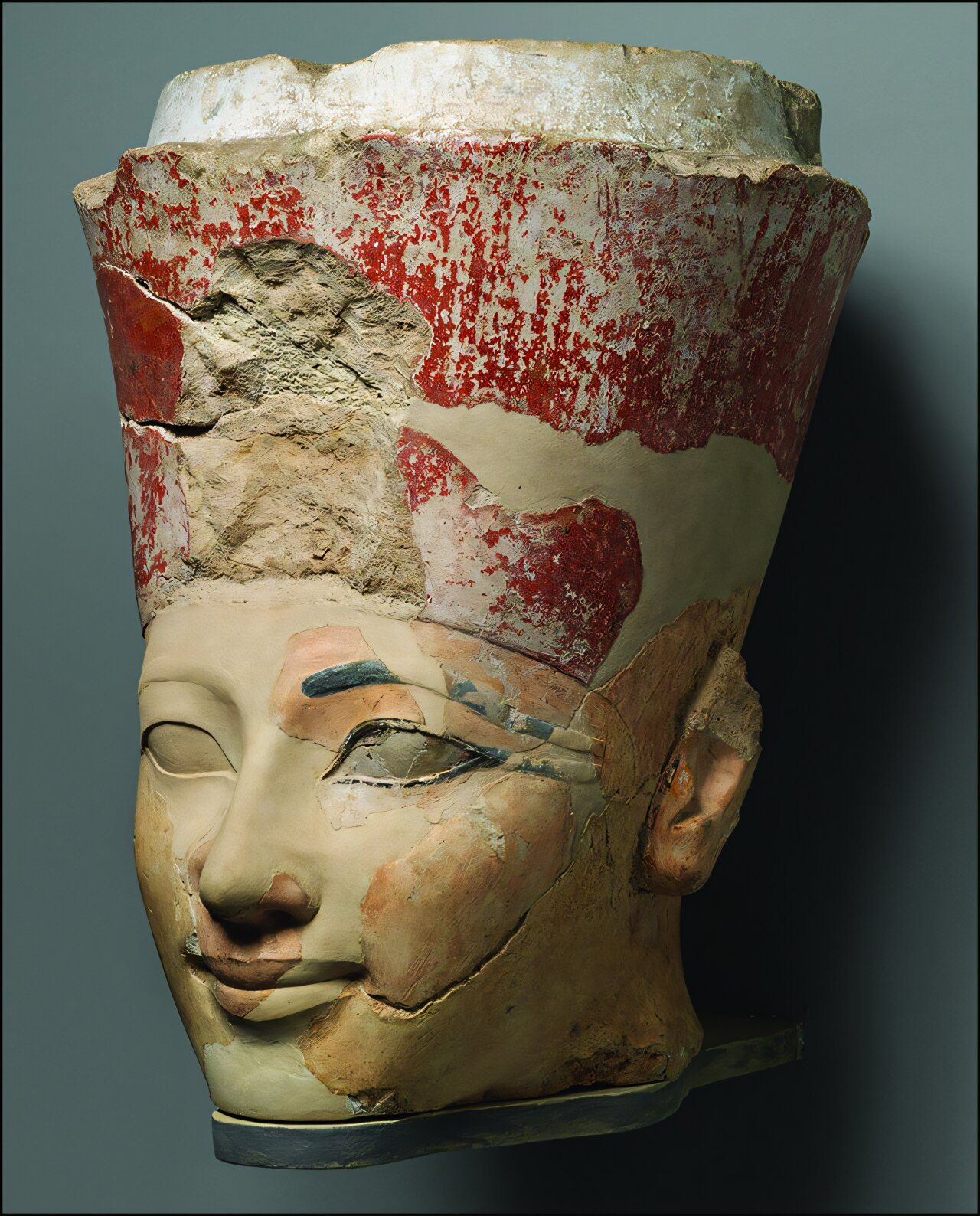

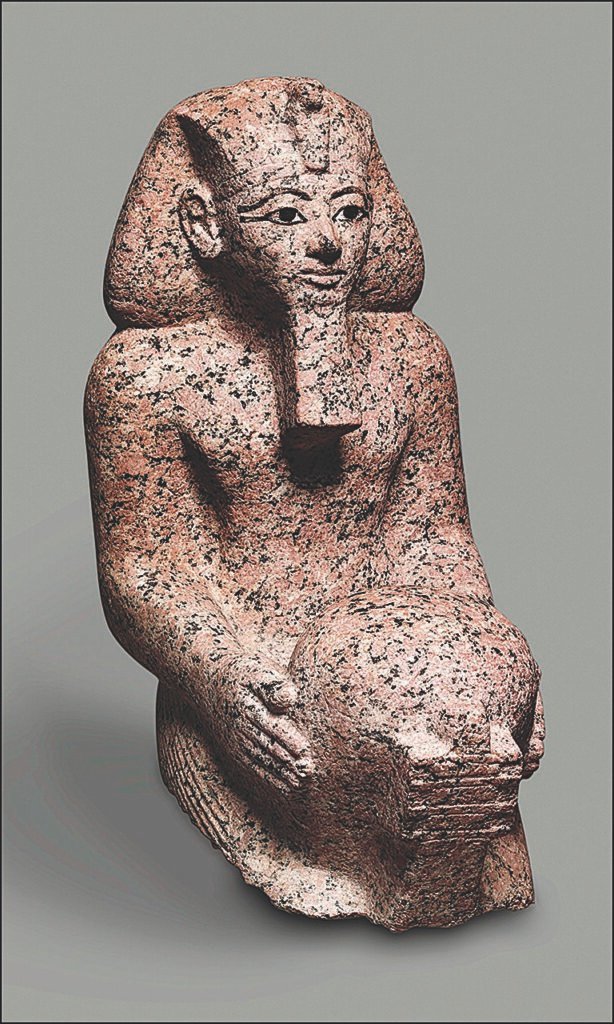

In the shadow of the cliffs at Deir el-Bahri, where sun-bleached stone holds centuries of royal ambition, ancient secrets are still revealing themselves—sometimes not in the unearthing of new ruins, but in the careful re-reading of old ones. A new study, based on long-forgotten field notes and photographs from 1920s excavations, now challenges a long-held belief: that the destruction of statues depicting Egypt’s most famous female pharaoh, Hatshepsut, was an act of political vengeance.

Instead, the damage may be less about defilement and more about tradition.

For decades, the prevailing view has been dramatic and, frankly, cinematic—after Hatshepsut’s death, her ambitious nephew and successor, Thutmose III, retaliated against her unprecedented rule by smashing her statues, erasing her image, and condemning her legacy. But according to new research by Jun Yi Wong of the University of Toronto, published in the journal Antiquity, the truth is likely more complicated and, in some ways, more reflective of ancient Egyptian ritual than royal spite.

The Queen Who Became a King

Hatshepsut’s reign was one of stability, prosperity, and monumental architecture. Rising to power around 1478 BCE, she initially ruled as regent for her young stepson, Thutmose III, but soon took on the full powers and titles of pharaoh—including the beard and male regalia traditionally reserved for kings. She was, in every sense, a trailblazer: a woman who navigated the patriarchal corridors of power in ancient Egypt and left behind a kingdom enriched by trade, diplomacy, and temple-building.

But that same act of defiance—assuming the male mantle of kingship—has long been viewed as the reason why, after her death, her memory was targeted for erasure. The shattered statues discovered at her mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahri seemed to confirm the story: a powerful woman, posthumously punished by a resentful heir.

Yet when Wong took a closer look, the pieces didn’t quite fit.

The Archives Speak

Wong delved into the archives of the 1922–1928 excavations conducted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Luxor. These records—many unpublished—included excavation diaries, correspondence, sketches, and early photographs. In them, he found a more complex picture, one that suggested the damage to Hatshepsut’s statuary was selective, and in some cases ritualistic, not simply the chaotic fury of political iconoclasm.

“While the ‘shattered visage’ of Hatshepsut has come to dominate the popular perception,” Wong notes, “such an image does not reflect the treatment of her statuary to its full extent. Many of her statues survive in relatively good condition, with their faces virtually intact.”

That fact is telling. In ancient Egypt, facial mutilation of statues was often a true act of erasure, believed to sever the spirit of the deceased from the mortal world. But Hatshepsut’s statues? In many cases, their faces were untouched. Their damage followed a curious pattern: broken at natural stress points—necks, waists, knees—exactly the way statues were ritually “deactivated” in Egyptian custom.

Deactivation, Not Desecration

This practice, known to Egyptologists as “deactivation”, was part of the spiritual logic that governed life and death in pharaonic Egypt. Statues weren’t just stone—they were vessels for divine power, and breaking them at joints was a formal way to release or neutralize that power.

“Such treatment does not necessarily denote hostility toward the individual depicted,” Wong explains. Instead, it was often standard protocol for retired or removed royal figures. Similar practices were applied to other pharaohs, including those never accused of defying convention the way Hatshepsut did.

In addition, Wong uncovered evidence that many statues were damaged after Thutmose III’s reign, during later periods of decline and reuse. The broken fragments of her image were often recycled—used as building materials, tools, or fill in other constructions—suggesting pragmatism more than revenge.

A More Nuanced Pharaoh

Wong’s conclusions don’t erase the fact that Hatshepsut faced some level of posthumous persecution. Her name was removed from inscriptions, her legacy obscured for centuries. But the idea that Thutmose III led a vindictive campaign to erase his stepmother may be an oversimplification of ancient politics and religious protocol.

“Unlike the other rulers, Hatshepsut did suffer a program of persecution, and its wider political implications cannot be overstated,” Wong acknowledges. “Yet, there is room for a more nuanced understanding of Thutmose III’s actions, which were perhaps driven by ritual necessity rather than outright antipathy.”

That nuance matters. It paints a picture not of a jealous successor destroying the memory of a powerful woman, but of a culture that treated the image of the king—whether male or female—as sacred, subject to ritual, not emotion.

Statues That Still Stand

The story of Hatshepsut has always been compelling: a woman who defied gender roles, ruled with wisdom, and left behind some of Egypt’s most iconic monuments. That her statues were broken seemed to mirror the fate of many women throughout history—powerful in life, punished in death.

But the new research offers a corrective. Her statues may be in pieces, but they are not lost. Their faces survive. Their presence endures. And if anything, the care with which they were “deactivated” speaks to a recognition of their power, even by those who may have sought to limit her legacy.

In re-examining the rubble, Wong has restored not just the physical image of Hatshepsut, but a deeper respect for her place in Egypt’s dynastic story.

She was not simply erased. She was remembered—ritually, carefully, and now, more fully than ever.

Reference: The afterlife of Hatshepsut’s statuary, Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.64