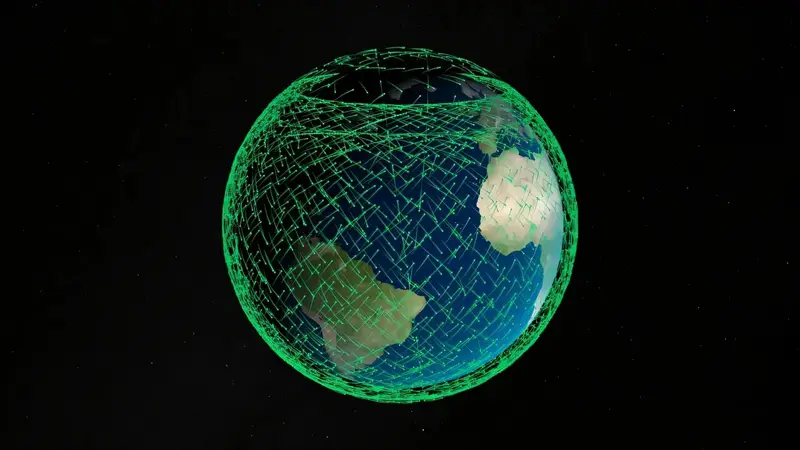

High above Earth, far beyond the reach of weather and borders, thousands of satellites race around the planet in carefully choreographed paths. They are invisible to most of us, yet they quietly support modern life, forming vast mega-constellations in low-Earth orbit. From the ground, this system can feel solid and dependable. From closer inspection, however, researchers now argue it looks far more like something else entirely. As one new study describes it, the system resembles a “House of Cards.”

That phrase, borrowed from everyday language and now famously tied to a television drama, returns to its original meaning here. It describes a structure that appears impressive but is fundamentally unstable. Sarah Thiele, who began this work as a Ph.D. student at the University of British Columbia and is now at Princeton, and her co-authors use the term deliberately in a new paper available as a pre-print on arXiv. Their message is clear and unsettling. The orbital environment we are rapidly filling with satellites may be far closer to collapse than most people realize.

When Close Calls Become the Norm

In the vastness of space, one kilometer might sound like a comfortable buffer. In low-Earth orbit, it is not. According to the paper, across all satellite mega-constellations, a “close approach,” defined as two satellites passing within less than one kilometer of each other, happens every 22 seconds. This is not an occasional anomaly. It is the background rhythm of the system.

Even focusing on a single network paints a tense picture. For Starlink alone, such close approaches occur once every 11 minutes. To prevent these encounters from turning into collisions, satellites must constantly maneuver. On average, each Starlink satellite performs 41 maneuvers per year to avoid running into other objects in orbit.

At first glance, this might sound reassuring. The system seems active, responsive, and carefully managed. Satellites detect potential dangers and adjust their paths. Engineers monitor the traffic. Collisions are avoided. But this appearance of control hides a deeper vulnerability. As any engineer will point out, most system failures do not come from normal operation. They come from edge cases, the rare but extreme conditions the system was never truly designed to handle.

The Sun as an Unpredictable Saboteur

One of the most dangerous edge cases identified in the paper comes not from human error or mechanical failure, but from the Sun itself. Solar storms, bursts of energy and particles from the Sun, can disrupt satellite operations in two major ways.

The first effect is atmospheric heating. When a solar storm hits Earth, it heats the upper atmosphere, causing it to expand. For satellites in low-Earth orbit, this creates increased drag. Their paths become less predictable, and they slow down slightly, losing altitude. To compensate, satellites must burn fuel to maintain their orbits. At the same time, the uncertainty introduced by this atmospheric change forces satellites to perform even more evasive maneuvers.

The authors point to a recent real-world example. During the “Gannon Storm” of May 2024, over half of all satellites in low-Earth orbit had to use at least some of their fuel to reposition themselves. This was not a hypothetical scenario or a simulation. It was a preview of how fragile the system becomes under stress.

When Satellites Go Blind and Silent

The second effect of solar storms is even more dangerous. Solar activity can disrupt or completely disable a satellite’s navigational and communication systems. When that happens, the satellite cannot receive commands or execute avoidance maneuvers. It becomes a fast-moving object in orbit with no ability to steer away from danger.

Combine this loss of control with increased atmospheric drag and positional uncertainty, and the result is a recipe for disaster. Satellites that cannot maneuver are more likely to collide. A single collision can produce debris, and that debris can trigger further collisions. This is the nightmare scenario known as Kessler syndrome.

Kessler syndrome is often discussed as a slow-moving catastrophe, one that unfolds over decades as debris accumulates. But the authors of this paper argue that the danger is far more immediate than that framing suggests.

The Clock That Measures How Fast Disaster Arrives

To capture the urgency of the situation, the researchers introduce a new concept called the Collision Realization and Significant Harm Clock, or the CRASH Clock. Rather than measuring how long it takes for debris to accumulate over decades, this metric asks a simpler and more frightening question. How long would it take for a catastrophic collision to occur if satellite operators suddenly lost the ability to command avoidance maneuvers.

According to their calculations, as of June 2025, that time is around 2.8 days. In other words, if operators could not send commands to their satellites, a catastrophic collision would likely occur in less than three days.

The contrast with the recent past is stark. In 2018, before the rise of mega-constellations, the same calculation produced a much longer window. Back then, operators would have had around 121 days before a similar collision became likely. The sky has become far more crowded in just a few years, and the margin for error has nearly vanished.

Perhaps most alarming is what happens even with a short disruption. If operators lose control for just 24 hours, the paper estimates a 30 percent chance of a catastrophic collision. Such an event could act as the seed for the decades-long cascade of debris that defines Kessler syndrome.

Warnings That Come Too Late

Solar storms do not arrive with generous notice. At best, scientists may have a day or two of warning. Even then, there is little that can be done beyond trying to safeguard satellites as much as possible. The atmosphere becomes dynamic and unpredictable, and managing satellites effectively requires real-time feedback and control.

The paper makes a sobering point. If that real-time control goes down, operators have only a few days to restore it before the entire system risks collapse. The house of cards does not fall slowly. It falls all at once.

This concern is not theoretical. The Gannon Storm of 2024 was the strongest solar storm in decades. Yet history shows that the Sun is capable of far worse.

A Nineteenth Century Event With Modern Consequences

In 1859, Earth experienced the Carrington Event, the strongest solar storm on record. At the time, there were no satellites, no global communication networks, and no orbital infrastructure to disrupt. Today, the same kind of event would have dramatically different consequences.

According to the paper, a solar storm on the scale of the Carrington Event would likely wipe out our ability to control satellites for far longer than three days. In such a scenario, the CRASH Clock would not just tick down. It would run out.

The implication is chilling. A single solar event, one with clear historical precedent, could trigger a chain reaction that destroys our satellite infrastructure and leaves humanity effectively Earth-bound for the foreseeable future. Launching new satellites into a debris-filled orbit would become nearly impossible. Access to space, something we increasingly take for granted, could be lost for generations.

Why This Research Matters

This is not a call for panic, but it is a call for honesty. Low-Earth orbit mega-constellations provide real technical benefits, and their capabilities are already deeply woven into modern society. At the same time, they introduce risks that extend far beyond any single company or nation.

The strength of this research lies in its clarity. It does not speculate wildly or rely on distant hypotheticals. It uses known data, real events, and careful calculations to show how narrow our safety margins have become. It reminds us that complex systems can appear stable right up until the moment they fail.

When the potential outcome is losing access to space for generations because of one particularly bad solar storm, informed decision-making becomes essential. This paper helps create that understanding. It forces us to confront the fragility of the systems we are building above our heads and to ask whether we are prepared for the risks we are taking.

The sky may look calm from the ground, but according to this research, it is balancing on a delicate edge. Understanding that reality may be the first step toward preventing the house of cards from falling.

More information: Sarah Thiele et al, An Orbital House of Cards: Frequent Megaconstellation Close Conjunctions, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2512.09643