Imagine a lonely galaxy, tucked away in a vast, barren region of space, far from the bustling crowds of stars and galaxies that crowd the cosmos. Yet, against all odds, this isolated galaxy is still making stars—new ones, no less. A team of Spanish astronomers recently took a fresh, deep look at this galaxy, known as NGC 6789, and the results have left them scratching their heads.

It was 1883 when NGC 6789, a blue compact dwarf galaxy, was first discovered. Located about 12 million light-years away in the Local Void, a region of space unusually devoid of galaxies, this galaxy has remained a quiet, distant enigma for over a century. But recently, astronomers have been taking a closer look at this oddball of a galaxy, and what they’ve found has raised more questions than answers.

An Isolated Galaxy with a Burst of Life

Despite its extreme isolation, NGC 6789 has been showing some unexpected activity. The galaxy’s center is actively producing new stars, a phenomenon that is usually linked to galaxies interacting with their neighbors or undergoing mergers. However, in the case of NGC 6789, there is no sign of interaction. No nearby galaxies, no tidal forces, no disturbances in its structure. Yet, somehow, this isolated galaxy is still managing to create new stars in its core.

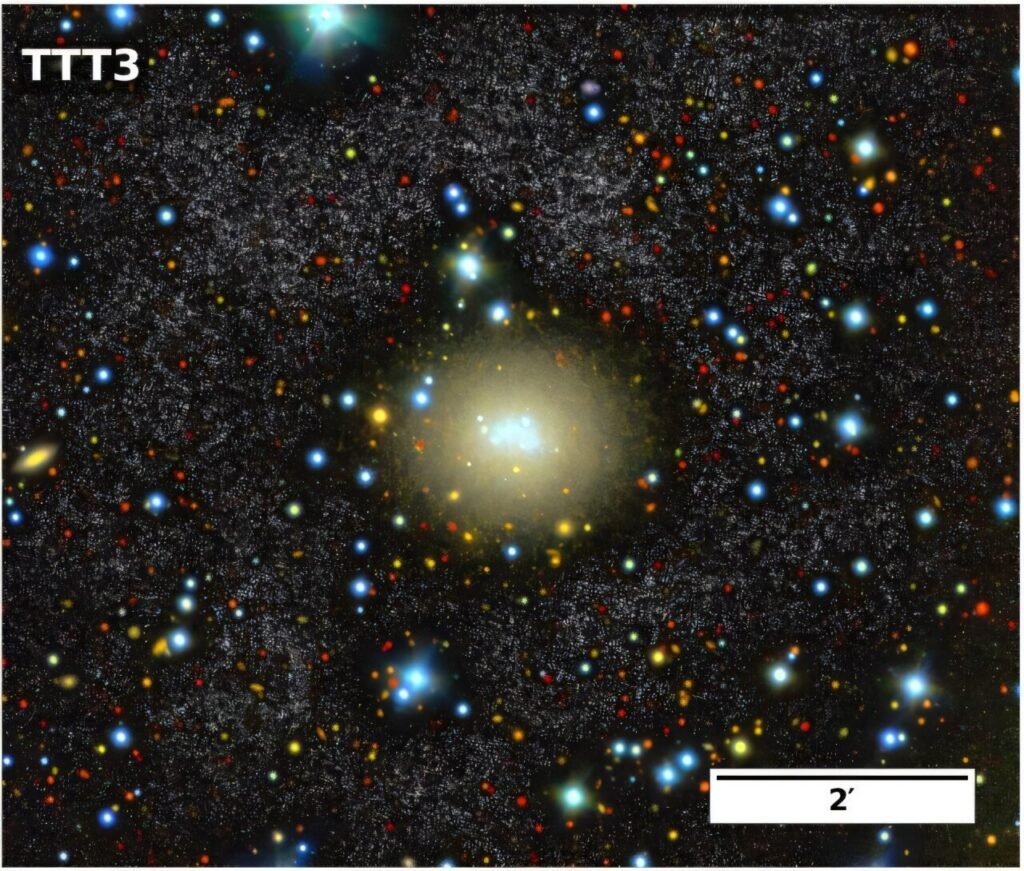

Previous studies revealed that about 4% of NGC 6789’s total stellar mass—around 100 million solar masses—has formed in the past 600 million years. This recent star formation is taking place at the galaxy’s center, which is surrounded by an older, redder elliptical structure. This curious contrast between the young, blue core and the older outer shell only deepens the mystery.

But what’s fueling this ongoing star formation in a galaxy so isolated, without any obvious external influences? This is the central question that the new observations seek to answer.

A New Look with the Two-Meter Twin Telescope

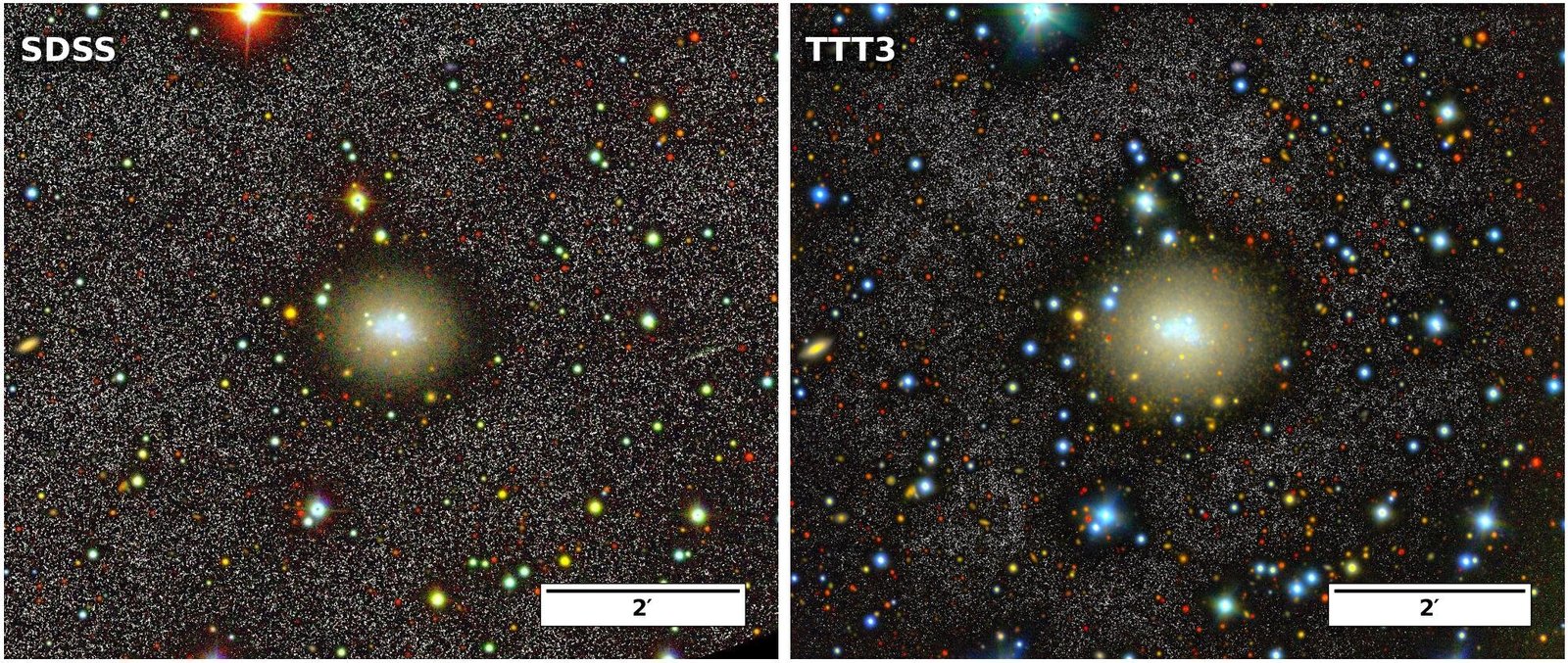

To shed light on this puzzle, a team of astronomers, led by Ignacio Trujillo of the University of La Laguna in Spain, set out to observe NGC 6789 in unprecedented detail. Using the Two-Meter Twin Telescope (TTT3), they aimed to capture deeper optical images of the galaxy, focusing on its outer regions, which had not been explored in such depth before.

“We present substantially deeper multiband imaging of NGC 6789 to explore its outer regions and search for faint features that may reveal evidence of past minor mergers or gas accretion events capable of supplying the fuel required to build its star-forming core,” the researchers explained in their paper.

The hope was that these new, more detailed observations would reveal some clue as to how NGC 6789 is managing to sustain its star-forming activity despite its isolation. Could there have been some hidden past merger, or perhaps a slow accumulation of gas from intergalactic space?

The Search for Clues in the Outer Regions

As the astronomers pored over the new data, they found no evidence of the expected signs of past mergers or cosmic collisions. The outer regions of the galaxy still retained their undisturbed elliptical shape, with no visible tidal features or merger remnants that might indicate that NGC 6789 had once interacted with other galaxies. The galaxy’s structure remained smooth and unperturbed, suggesting that the star formation in the center could not be the result of a past collision or merger.

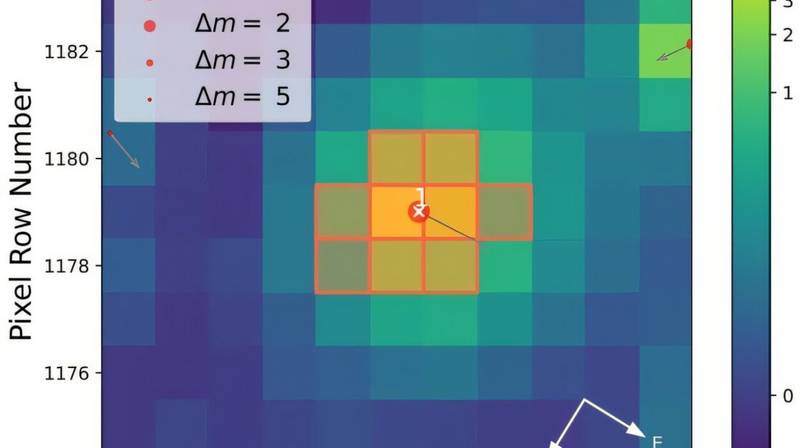

The researchers also used their data to estimate how much stellar mass might be surrounding the galaxy as a result of any small satellite galaxies that might have been disrupted by the larger galaxy. The calculation put an upper limit on this possible mass at around 200,000 solar masses—a small amount in comparison to the 4 million solar masses of new stars being created in the galaxy’s core.

The Great Unknown: Where is the Gas Coming From?

So, what is the source of the gas fueling the starburst at the heart of NGC 6789? The team was unable to find any definitive evidence to suggest that the gas came from a past merger or interaction. Instead, they propose two possibilities.

“Its recent central star formation was likely produced either by in-situ residual gas or by the accretion of external pristine gas not associated with a minor merging activity,” the researchers suggest. In other words, the gas that is forming new stars in the galaxy’s center could either be leftover gas from the galaxy itself or fresh gas that has been slowly drawn in from intergalactic space—a process known as accretion.

Interestingly, this kind of “pristine” gas, which has not been enriched by elements created in past generations of stars, would be very rare in the universe, making its presence in NGC 6789 even more intriguing. If the galaxy is pulling in this rare, unprocessed gas from its surroundings, it could be providing a crucial missing piece to the puzzle of how star formation happens in such an isolated environment.

Why This Research Matters

This research is important because it challenges our understanding of how galaxies form and evolve. For many galaxies, star formation is driven by interactions with their neighbors or by the chaotic events of galactic mergers. NGC 6789, however, is doing things differently. By continuing to form stars despite its isolation and lack of external influence, it presents an opportunity to study the process of star formation in a pristine environment, where the usual explanations don’t apply.

The findings suggest that even in the most isolated corners of the universe, star formation can still occur under the right conditions, powered by either residual gas within the galaxy or by the slow accumulation of gas from the wider cosmos. The mystery of how galaxies like NGC 6789 continue to make new stars could have important implications for our understanding of galaxy evolution, especially in the more barren regions of space.

More information: Ignacio Trujillo et al, Deep imaging of the very isolated dwarf galaxy NGC6789, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2511.07041